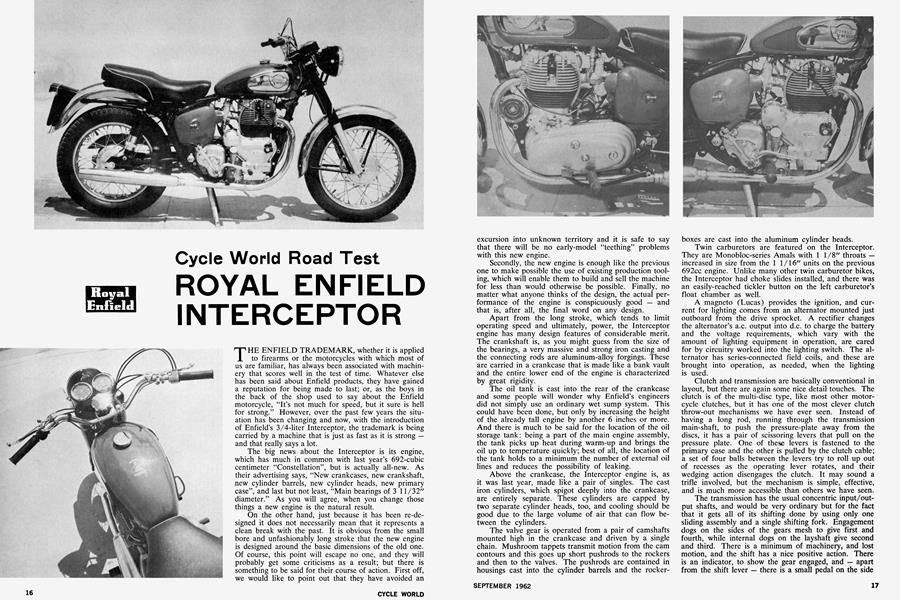

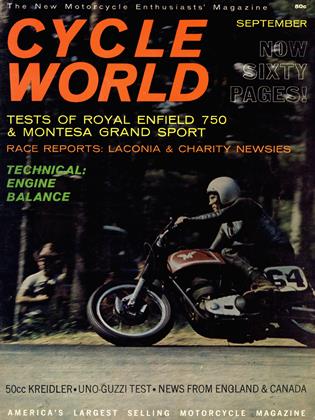

ROYAL ENFIELD INTERCEPTOR

Cycle World Road Test

THE ENFIELD TRADEMARK, whether it is applied to firearms or the motorcycles with which most of us are familiar, has always been associated with machinery that scores well in the test of time. Whatever else has been said about Enfield products, they have gained a reputation for being made to last; or, as the boys in the back of the shop used to say about the Enfield motorcycle, “It’s not much for speed, but it sure is hell for strong.” However, over the past few years the situation has been changing and now, with the introduction of Enfield’s 3/4-liter Interceptor, the trademark is being carried by a machine that is just as fast as it is strong — and that really says a lot.

The big news about the Interceptor is its engine, which has much in common with last year’s 692-cubic centimeter “Constellation”, but is actually all-new. As their advertising says, “New crankcases, new crankshaft, new cylinder barrels, new cylinder heads, new primary case”, and last but not least, “Main bearings of 3 11/32" diameter.” As you will agree, when you change those things a new engine is the natural result.

On the other hand, just because it has been re-designed it does not necessarily mean that it represents a clean break with the past. It is obvious from the small bore and unfashionably long stroke that the new engine is designed around the basic dimensions of the old one. Of course, this point will escape no one, and they will probably get some criticisms as a result; but there is something to be said for their course of action. First off, we would like to point out that they have avoided an excursion into unknown territory and it is safe to say that there will be no early-model “teething” problems with this new engine.

Secondly, the new engine is enough like the previous one to make possible the use of existing production tooling, which will enable them to build and sell the machine for less than would otherwise be possible. Finally, no matter what anyone thinks of the design, the actual performance of the engine is conspicuously good — and that is, after all, the final word on any design.

Apart from the long stroke, which tends to limit operating speed and ultimately, power, the Interceptor engine has many design features of considerable merit. The crankshaft is, as you might guess from the size of the bearings, a very massive and strong iron casting and the connecting rods are aluminum-alloy forgings. These are carried in a crankcase that is made like a bank vault and the entire lower end of the engine is characterized by great rigidity.

The oil tank is cast into the rear of the crankcase and some people will wonder why Enfield’s engineers did not simply use an ordinary wet sump system. This could have been done, but only by increasing the height of the already tall engine by another 6 inches or more. And there is much to be said for the location of the oil storage tank: being a part of the main engine assembly, the tank picks up heat during warm-up and brings the oil up to temperature quickly; best of all, the location of the tank holds to a minimum the number of external oil lines and reduces the possibility of leaking.

Above the crankcase, the Interceptor engine is, as it was last year, made like a pair of singles. The cast iron cylinders, which spigot deeply into the crankcase, are entirely separate. These cylinders are capped by two separate cylinder heads, too, and cooling should be good due to the large volume of air that can flow between the cylinders.

The valve gear is operated from a pair of camshafts mounted high in the crankcase and driven by a single chain. Mushroom tappets transmit motion from the cam contours and this goes up short pushrods to the rockers and then to the valves. The pushrods are contained in housings cast into the cylinder barrels and the rockerboxes are cast into the aluminum cylinder heads.

Twin carburetors are featured on the Interceptor. They are Monobloc-series Amals with 1 1/8" throats — increased in size from the 1 1/16" units on the previous 692cc engine. Unlike many other twin carburetor bikes, the Interceptor had choke slides installed, and there was an easily-reached tickler button on the left carburetor’s float chamber as well.

A magneto (Lucas) provides the ignition, and current for lighting comes from an alternator mounted just outboard from the drive sprocket. A rectifier changes the alternator’s a.c. output into d.c. to charge the battery and the voltage requirements, which vary with the amount of lighting equipment in operation, are cared for by circuitry worked into the lighting switch. The alternator has series-connected field coils, and these are brought into operation, as needed, when the lighting is used.

Clutch and transmission are basically conventional in layout, but there are again some nice detail touches. The clutch is of the multi-disc type, like most other motorcycle clutches, but it has one of the most clever clutch throw-out mechanisms we have ever seen. Instead of having a long rod, running through the transmission main-shaft, to push the pressure-plate away from the discs, it has a pair of scissoring levers that pull on the pressure plate. One of these levers is fastened to the primary case and the other is pulled by the clutch cable; à set of four balls between the levers try to roll up out of recesses as the operating lever rotates, and their wedging action disengages the clutch. It may sound a trifle involved, but the mechanism is simple, effective, and is much more accessible than others we have seen.

The transmission has the usual concentric input/output shafts, and would be very ordinary but for the fact that it gets all of its shifting done by using only one sliding assembly and a single shifting fork. Engagement dogs on the sides of the gears mesh to give first and fourth, while internal dogs on the layshaft give second and third. There is a minimum of machinery, and lost motion, and the shift has a nice positive action. There is an indicator, to show the gear engaged, and — apart from the shift lever — there is a small pedal on the side of the transmission that, when depressed, pops the box into neutral.

Engine and transmission are set into a frame that is big, and tall, and gives excellent results. Although a single-loop frame is really not the best type to be used in combination with such a powerful engine, the Interceptor has enough added bracing festooned around the basic structure to provide the necessary strength.

The suspension consists of telescopic forks in front and swing-arms at the rear, with two-position spring/ damper units (that can be set by hand) to accommodate changes in load. The springing is quite stiff — by average road-rider standards — but with so much speed on tap one needs the stability that only comes with reasonably stiff suspensions. In fact, all things considered, we would have to rate the Enfield Interceptor as one of the definitely superior big road machines. It is too tall to be very agile and a full-tilt passage through a series of fast S-bends will make a rider work, but it is extremely stable and can be cornered with great speed and confidence.

Unfortunately, the brakes were not quite up to the high standard of the road holding. The twin-drum, four-shoe, 6-inch front brakes that were used last year have been discontinued in favor of a single, 7-inch drum and two-shoe unit and we are not at all sure this is a move ahead. The brakes (a 7-inch drum is used on the rear wheel, too) are large enough, and they will definitely stop the machine, but they made some very peculiar squeaking noises at low speeds and shuddered somewhat when used hard. On a bike of less formidable performance they would have been fine, but the Interceptor will cruise af 100 mph and at that speed they were no better than adequate.

The cruising speed of the Interceptor is higher than almost anything else available today — due in no small part to its 4.10 overall gear ratio. At a true 100 mph it is cranking over only 5200 rpm and down at the more normal cruising pace of 70 mph it turns a leisurely 3600 rpm. These low engine speeds mean long engine life and we wish more motorcycles had the same sort of gearing. However, pulling such a tall top gear limits the bike’s performance; if you can call an 89 mph standing 1 /4-mile and a top speed of nearly 120 mph limited. The top speed (particularly, suffers greatly; in fourth gear, the engine simply cannot get turning fast enough to develop full power. We suspect that the Interceptor would be faster with, say, 4.25:1 overall gearing. Thus equipped, there is a strong chance that the Interceptor would be able to pull its power peak in fourth, giving a speed of almost 125 mph. Of course, the speed with the stock gearing is top-flight and it gives the most pleasant, strain-free cruising we have experienced in a long time.

Enfield’s Interceptor takes them into the high-performance motorcycle business with a flourish. An engine with that many cubic inches of displacement simply won’t take no for an answer and a very high level of performance is the natural result. Added to that there is the obvious strength of the machine and the quality of its finish — which was good. It is comfortable to ride and the controls, speedometer and tach were, generally, right where they should have been. Only the kill-button (on the handlebars, near the steering head) could have been better positioned. We did not like the fact that there was no fuel reserve, and the Interceptor was a 5to 10-kick start even after we found the combination. But, even with all that, it left us with the thought that anyone who buys a big bike without giving the Interceptor a try will be doing himself a great disservice. •

ENFIELD INTERCEPTOR

SPECIFICATIONS

$1168

POWER TRANSMISSION

PERFORMANCE

ACCELERATION

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle Round Up

SEPTEMBER 1962 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Service Department

SEPTEMBER 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

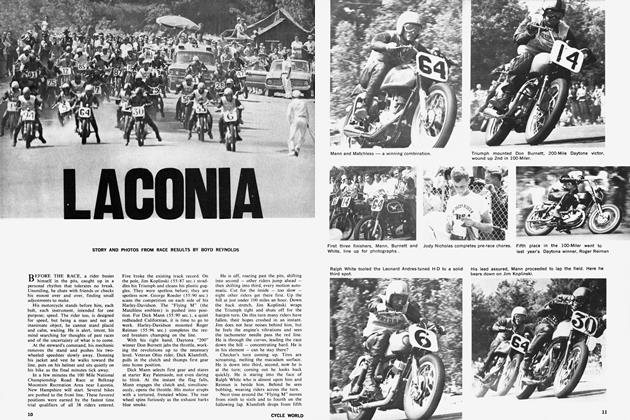

Laconia

SEPTEMBER 1962 By Boyd Reynolds -

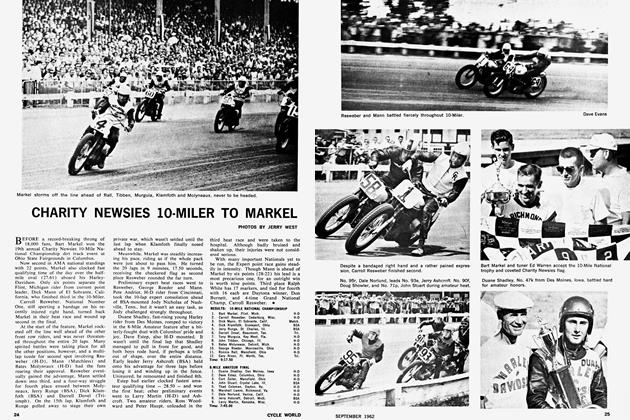

Charity Newsies 10-Miler To Markel

SEPTEMBER 1962 -

Technical

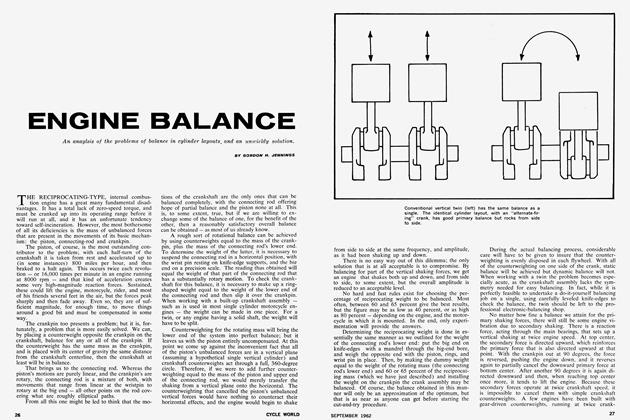

TechnicalEngine Balance

SEPTEMBER 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

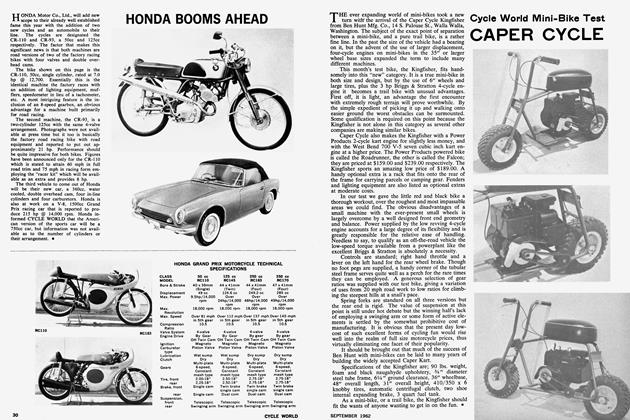

Cycle World Mini-Bike Test

Cycle World Mini-Bike TestCaper Cycle

SEPTEMBER 1962