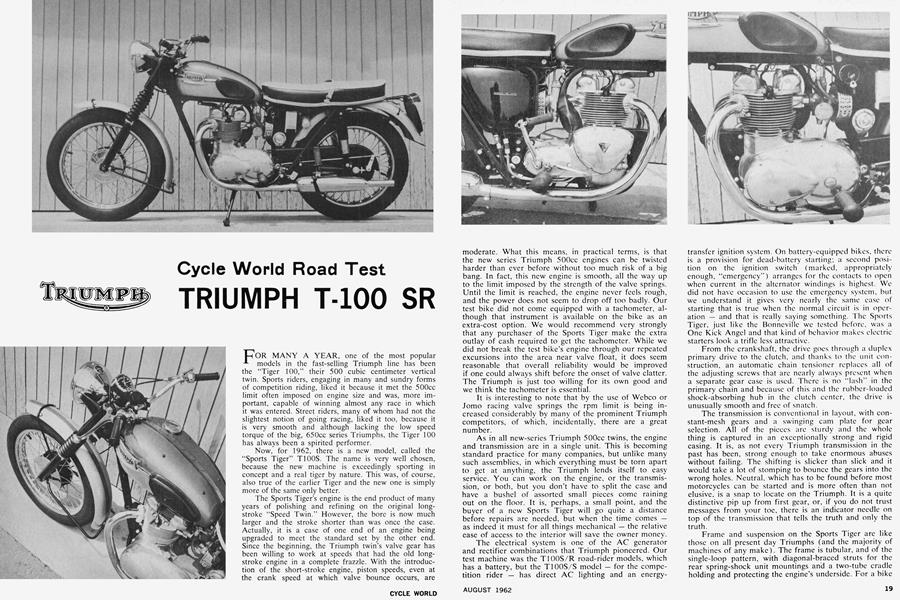

TRIUMPH T-100 SR

Cycle World Road Test

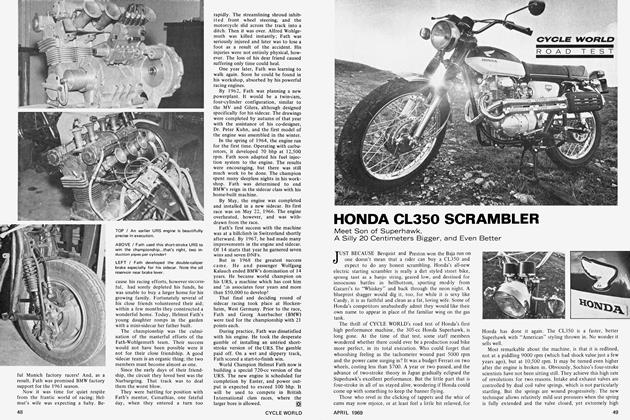

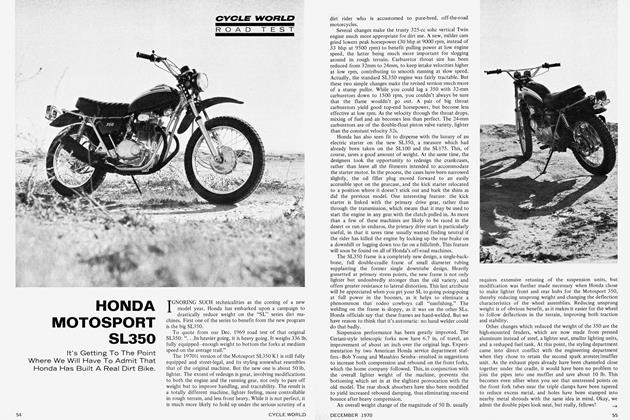

FOR MANY A YEAR, one of the most popular models in the fast-selling Triumph line has been the “Tiger 100,“ their 500 cubic centimeter vertical twin. Sports riders, engaging in many and sundry forms of competition riding, liked it because it met the 500cc limit often imposed on engine size and was, more important, capable of winning almost any race in which it was entered. Street riders, many of whom had not the slightest notion of going racing, liked it too, because it is very smooth and although lacking the low speed torque of the big, 650cc series Triumphs, the Tiger 100 has always been a spirited performer.

Now, for 1962, there is a new model, called the “Sports Tiger” T100S. The name is very well chosen, because the new machine is exceedingly sporting in concept and a real tiger by nature. This was, of course, also true of the earlier Tiger and the new one is simply more of the same only better.

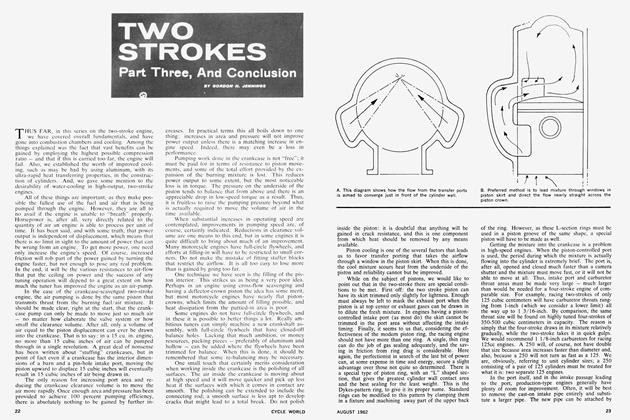

The Sports Tiger’s engine is the end product of many years of polishing and refining on the original longstroke “Speed Twin.” However, the bore is now much larger and the stroke shorter than was once the case. Actually, it is a case of one end of an engine being upgraded to meet the standard set by the other end. Since the beginning, the Triumph twin’s valve gear has been willing to work at speeds that had the old longstroke engine in a complete frazzle. With the introduction of the short-stroke engine, piston speeds, even at the crank speed at which valve bounce occurs, are moderate. What this means, in practical terms, is that the new series Triumph 500cc engines can be twisted harder than ever before without too much risk of a big bang. In fact, this new engine is smooth, all the way up to the limit imposed by the strength of the valve springs. Until the limit is reached, the engine never feels rough, and the power does not seem to drop off too badly. Our test bike did not come equipped with a tachometer, although that instrument is available on the bike as an extra-cost option. We would recommend very strongly that any purchaser of the Sports Tiger make the extra outlay of cash required to get the tachometer. While we did not break the test bike’s engine through our repeated excursions into the area near valve float, it does seem reasonable that overall reliability would be improved if one could always shift before the onset of valve clatter. The Triumph is just too willing for its own good and we think the tachometer is essential.

It is interesting to note that by the use of Wcbco or Jomo racing valve springs the rpm limit is being increased considerably by many of the prominent Triumph competitors, of which, incidentally, there are a great number.

As in all new-serics Triumph 500cc twins, the engine and transmission are in a single unit. This is becoming standard practice for many companies, but unlike many such assemblies, in which everything must be torn apart to get at anything, the Triumph lends itself to easy service. You can work on the engine, or the transmission, or both, but you don’t have to split the case and have a bushel of assorted small pieces come raining out on the floor. It is, perhaps, a small point, and the buyer of a new Sports Tiger will go quite a distance before repairs are needed, but when the time comes — as indeed it must for all things mechanical — the relative ease of access to the interior will save the owner money.

The electrical system is one of the AC generator and rectifier combinations that Triumph pioneered. Our test machine was the T100S./R road-rider models, which has a battery, but the T100S/S model — for the competition rider — has direct AC lighting and an energytransfer ignition system. On battery-equipped bikes, there is a provision for dead-battery starting; a second position on the ignition switch (marked, appropriately enough, “emergency”) arranges for the contacts to open when current in the alternator windings is highest. We did not have occasion to use the emergency system, but we understand it gives very nearly the same ease of starting that is true when the normal circuit is in operation — and that is really saying something. The Sports Tiger, just like the Bonneville we tested before, was a One Kick Angel and that kind of behavior makes electric starters look a trifle less attractive.

From the crankshaft, the drive goes through a duplex primary drive to the clutch, and thanks to the unit construction, an automatic chain tensioner replaces all of the adjusting screws that are nearly always present when a separate gear case is used. There is no “lash” in the primary chain and because of this and the rubber-loaded shock-absorbing hub in the clutch center, the drive is unusually smooth and free of snatch.

The transmission is conventional in layout, with constant-mesh gears and a swinging cam plate for gear selection. All of the pieces arc sturdy and the whole thing is captured in an exceptionally strong and rigid casing. It is, as not every Triumph transmission in the past has been, strong enough to take enormous abuses without failing. The shifting is slicker than slick and it would take a lot of stomping to bounce the gears into the wrong holes. Neutral, which has to be found before most motorcycles can be started and is more often than not elusive, is a snap to locate on the Triumph. It is a quite distinctive pip up from first gear, or, if you do not trust messages from your toe, there is an indicator needle on top of the transmission that tells the truth and only the truth.

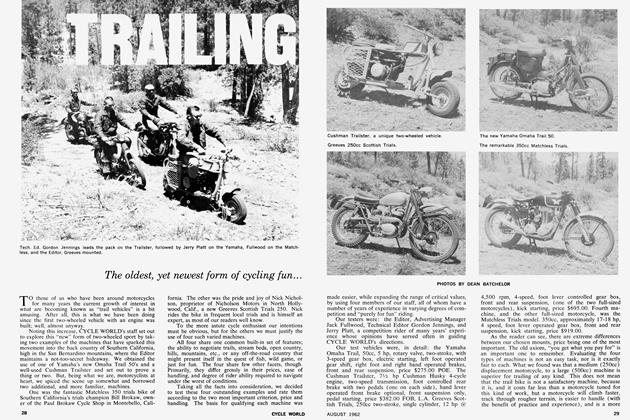

Frame and suspension on the Sports Tiger are like those on all present day Triumphs (and the majority of machines of any make). The frame is tubular, and of the single-loop pattern, with diagonal-braced struts for the rear spring-shock unit mountings and a two-tube cradle holding and protecting the engine's underside. For a bike that is intended for a wide variety of uses, it is amazingly softly sprung. Naturally, it does not have the true “balloon” ride favored by the more conservative rider, but it is rather spongy by sporting standards. In fact, for anything more vigorous than medium-fast touring, we think the suspension should be stiffened somewhat. We have thought the same thing about some other bikes, too, but they were not propelled along by the Triumph’s engine or at the Triumph's pace and that is why we make special mention of this here. The Sports Tiger has a marvelous engine, transmission and brakes, and the rider who wants to use all of these to their potential limit will want to put heavier oil in the front forks, and stiffer springs around the rear dampers.

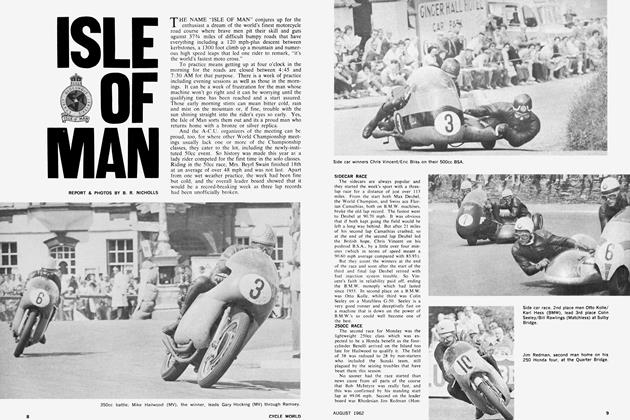

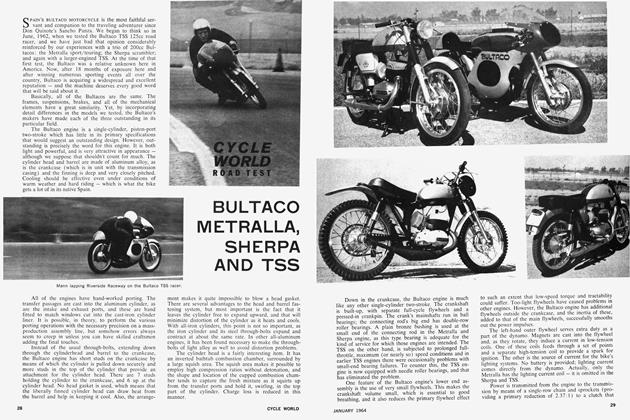

Generally, riding the Sports Tiger was grand fun, and we were sorry to see it returned to Johnson Motors in Pasadena, who are the distributors here. It was terrifically smooth — which we have already said, but cannot say enough — and it goes down the road like no other 500cc machine we have ridden recently. The clutch action is easy on the take-up, and has a weldedtogether grip when all the way home. On the Lions Club drag-strip, in Long Beach, California (where we now do all of our acceleration work) we startled all present by going out with lights, mufflers and licenseplate, looking very touring on a strip that ordinarily sees only all-out drag machinery, and banged off run after run at over 80 mph. The Tiger was a bit slow away from the line, and that hurt our e.t., but once underway it would really howl. It is not particularly at home on the drag strip, but it certainly managed to rise to the occasion in an honorable fashion.

The Tiger’s top speed of 100 mph represents only what it was capable of doing with the standard gearing. The power peak for the engine is reached at 92 mph, and the engine is getting near valve crash when the bike passes the 100-mark. Probably, even though there was no audible rattling, the valves were no longer following the cam at the maximum speed. The flat-out enthusiasts will want to gear this new Tiger differently — but the standard gearing is perfectly selected for allaround riding.

On the whole, we were greatly impressed by the Sports Tiger. It is as nicely finished a bit of machinery as one could want, and the color scheme, in metallic blue and grey, is an eye-catcher if ever one existed. Performance, while not up to the level of the “hot-cam, high-compression” versions one sees winning all of the races, is all that can be had without compromising smoothness and reliability and is pretty good anyway. Finally, is it nice enough and fast enough so that we would pay our hard-earned money for it? You bet your sweet life it is! •

TRIUMPH T100S/R

$974.00