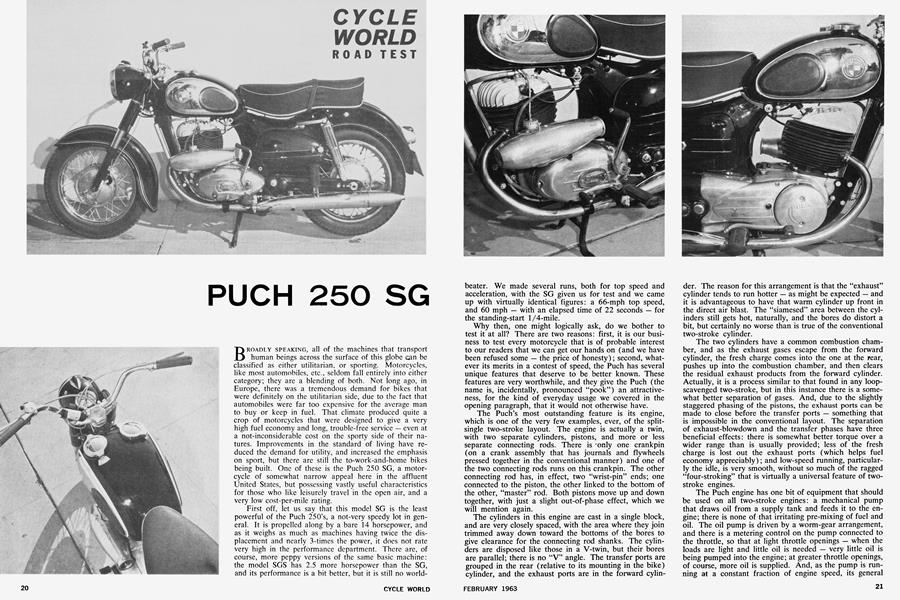

PUCH 250 SG

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

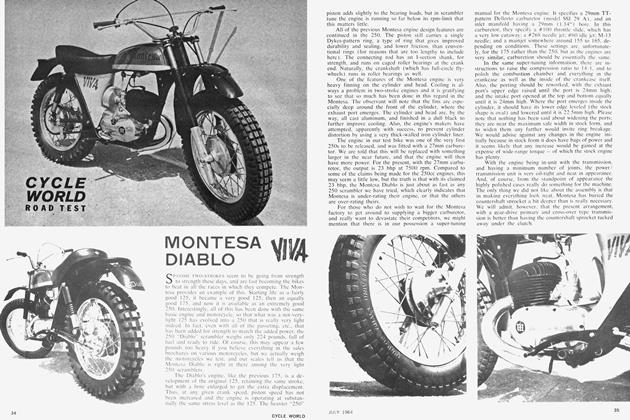

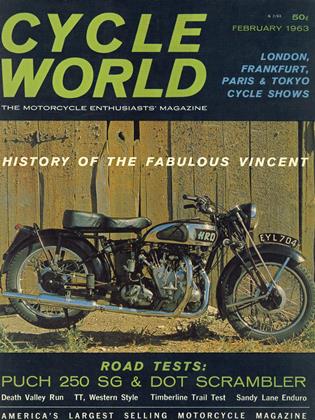

BROADLY SPEAKING, all of the machines that transport human beings across the surface of this globe can be classified as either utilitarian, or sporting. Motorcycles, like most automobiles, etc., seldom fall entirely into either category; they are a blending of both. Not long ago, in Europe, there was a tremendous demand for bikes that were definitely on the utilitarian side, due to the fact that automobiles were far too expensive for the average man to buy or keep in fuel. That climate produced quite a crop of motorcycles that were designed to give a very high fuel economy and long, trouble-free service — even at a not-inconsiderable cost on the sporty side of their natures. Improvements in the standard of living have reduced the demand for utility, and increased the emphasis on sport, but there are still the to-work-and-home bikes being built. One of these is the Puch 250 SG, a motorcycle of somewhat narrow appeal here in the affluent United States, but possessing vastly useful characteristics for those who like leisurely travel in the open air, and a very low cost-per-mile rating.

First off, let us say that this model SG is the least powerful of the Puch 250's, a not-very speedy lot in general. It is propelled along by a bare 14 horsepower, and as it weighs as much as machines having twice the displacement and nearly 3-times the power, it does not rate very high in the performance department. There are, of course, more peppy versions of the same basic machine: the model SGS has 2.5 more horsepower than the SG, and its performance is a bit better, but it is still no worldbeater. We made several runs, both for top speed and acceleration, with the SG given us for test and we came up with virtually identical figures: a 66-mph top speed, and 60 mph — with an elapsed time of 22 seconds — for the standing-start 1/4-mile.

Why then, one might logically ask, do we bother to test it at all? There are two reasons: first, it is our business to test every motorcycle that is of probable interest to our readers that we can get our hands on (and we have been refused some — the price of honesty) ; second, whatever its merits in a contest of speed, the Puch has several unique features that deserve to be better known. These features are very worthwhile, and they give the Puch (the name is, incidentally, pronounced "pook") an attractiveness, for the kind of everyday usage we covered in the opening paragraph, that it would not otherwise have.

The Puch's most outstanding feature is its engine, which is one of the very few examples, ever, of the splitsingle two-stroke layout. The engine is actually a twin, with two separate cylinders, pistons, and more or less separate connecting rods. There is 'only one crankpin (on a crank assembly that has journals and flywheels pressed together in the conventional manner) and one of the two connecting rods runs on this crankpin. The other connecting rod has, in effect, two "wrist-pin" ends; one connected to the piston, the other linked to the bottom of the other, "master" rod. Both pistons move up and down together, with just a slight out-of-phase effect, which we will mention again.

The cylinders in this engine are cast in a single block, and are very closely spaced, with the area where they join trimmed away down toward the bottoms of the bores to give clearance for the connecting rod shanks. The cylinders are disposed like those in a V-twin, but their bores are parallel; there is no "V" angle. The transfer ports are grouped in the rear (relative to its mounting in the bike) cylinder, and the exhaust ports are in the forward cylinder. The reason for this arrangement is that the "exhaust" cylinder tends to run hotter — as might be expected — and it is advantageous to have that warm cylinder up front in the direct air blast. The "siamesed" area between the cylinders still gets hot, naturally, and the bores do distort a bit, but certainly no worse than is true of the conventional two-stroke cylinder.

The two cylinders have a common combustion chamber, and as the exhaust gases escape from the forward cylinder, the fresh charge comes into the one at the rear, pushes up into the combustion chamber, and then clears the residual exhaust products from the forward cylinder. Actually, it is a process similar to that found in any loopscavenged two-stroke, but in this instance there is a somewhat better separation of gases. And, due to the slightly staggered phasing of the pistons, the exhaust ports can be made to close before the transfer ports — something that is impossible in the conventional layout. The separation of exhaust-blowdown and the transfer phases have three beneficial effects: there is somewhat better torque over a wider range than is usually provided; less of the fresh charge is lost out the exhaust ports (which helps fuel economy appreciably) ; and low-speed running, particularly the idle, is very smooth, without so much of the ragged "four-stroking" that is virtually a universal feature of twostroke engines.

The Puch engine has one bit of equipment that should be used on all two-stroke engines: a mechanical pump that draws oil from a supply tank and feeds it to the engine; there is none of that irritating pre-mixing of fuel and oil. The oil pump is driven by a worm-gear arrangement, and there is a metering control on the pump connected to the throttle, so that at light throttle openings — when the loads are light and little oil is needed — very little oil is being pumped into the engine; at greater throttle openings, of course, more oil is supplied. And, as the pump is running at a constant fraction of engine speed, its general delivery rate closely matches lubrication requirements. It is, in all, a marvelous arrangement, and one that might well be applied to all two-strokes.

The clutch and transmission are quite conventional, with all-indirect gearing (3rd has a 1:1 ratio, but passes through a pair of gears, nonetheless). The transmission feels very heavy, to the shifter's foot, and all gear changes are accompanied by a pronounced "clunk." The shift is positive, and moves the machinery in and out of mesh in a sure manner, but the rider is given the distinct impression that the gears must be as big, and heavy, as millstones. If this transmission is, in general service, anything like as beefy and strong as it feels, then it will never break.

One of the things we liked on the Puch, and something that seems to be coming into wider use, is an enclosure around the rear chain. In there, it can be properly oiled and protected against abrasive particles, and it is one of many items that contribute to reliability on this machine.

The Puch's frame is of pressed steel, and follows the backbone pattern fairly closely, except that there is a tubular member that loops down under the engine. Enclosures just ahead of the rear wheel contain a tool-roll, and the battery." The tank is divided into two compartments with separate fillers: one for gasoline; the other for oil. A three-position, off-on-reverse fuel tap is located under the tank, where a very short fuel line leads down to the engine's side-mounted carburetor. This carburetor, incidentally, has a great, ghastly-big fairling hanging on it, the purpose of which is to filter air and silence intake noise (or to fool people into thinking the bike carries an auxiliary rocket motor, we're not sure which).

Front and rear suspensions are conventional in layout, and are moderately soft and moderately good in action, and more than adequate for anything the bike is capable of doing. The wheels and tires are of the same size, front and rear, and are, in point of fact, interchangeable. This machine is intended for light sidecar work, and the interchangeability of wheels and tires is very important in that respect. The wheels may be removed for repairs by simply disconnecting such things as brake fittings and bunging-out the axle shaft.

Starting is very easy: both tickler and choke are provided, and the engine lights-off, either hot or cold, with little bother. And, like most two-strokes, it runs very well without the benefit of choking while it is still quite cold — an item of some importance when the machine is used for travelling to and from one's place of employment.

Riding position and the workings of the controls are good, if not inspiring. Everything feels rather ponderous, call it substantial if you prefer, and it gives one the definite impression — which our performance tests subsequently confirmed — that the bike would refuse to be hurried along. It is a bike with a great deal of unhurriable Teutonic dignity.

In the finish department, the Puch scores very high marks. There is a lot of enamel and chromium-plating and polished aluminum, and all of the miscellaneous hardware — such as control levers, etc. — are not only nicely made but look so strong that they couldn't be knocked-off with a hammer.

Milne Brothers, in Pasadena, California, who are the distributors of the Puch and who were kind enough to loan us this one for test, do not expect to sell one of these machines to everyone who walks in their doors. However, they have delivered a lot of Puch motorcycles to the commuting and/or back-to-nature rider, who would rather be sure of getting there and is not terribly interested in getting there first. And, too, the Puch engine has shown that it can be jiggered successfully to make it haul the bike along at a faster clip if that is what the rider wants. •

PUCH 250 SG

SPECIFICATIONS

$560

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue