THE SERVICE DEPARTMENT

GORDON H. JENNINGS

POPPET IN THE PISTON

I have just finished reading your interesting article on the two-stroke engine. In the course of so doing an idea came to mind: why would it not be possible to provide a passage from the crankcase to the cylinder through the top of the piston? Perhaps it could be done by way of a lightly loaded poppet valve in the top of the piston. P.S. Would it be possible to obtain back issues of your magazine? R. M. Moore Redondo Beach, Calif.

Your idea is not without merit, nor is it entirely original. The possibility of dispensing with some of those bothersome ports in the cylinder has prompted many a designer to try leading the mixture up through the piston. However, to the best of my knowledge it is a layout that has never been successful except in miniature engines — such as those made for model airplanes.

The reasons for the lack of success are in two spheres: first, there is the problem of making a piston that will not distort too much due to the interior convolutions necessary; secondly, no one has ever dealt satisfactorily with the inertia effects that arise as the mechanism is scaled up. At precisely the moment when the valve is supposed to be opening, there is a heavy inertia load holding it shut. Unless the valve is exceedingly light, pressure in the crankcase, unaided, will not be enough to lift it open. Some form of mechanical actuation could, of course, be provided, but that would negate the two-stroke’s fundamental attraction, which is its lack of mechanical complexity.

To answer your last question — and the questions of many people who have asked if previous issues of CYCLE WORLD can be obtained — I am happy to say that there are some copies available. These may be had by sending us 50 cents for each issue desired. Incidentally, those readers who are frugally inclined can avoid having to pay 50 cents for back issues by simply spending 35 cents when the issues are current, and available at the local newsstand.

MAXIMUM SPEEDS

I have a number of questions to ask in relation to your road tests. I notice that there are sometimes great differences in the number of rpm when gears are changed on some bikes.

For example, in the Norton Manxman test, third gear produces 111 mph at 7800 rpm, while fourth gear produces 105 mph at only 6000 rpm. By extrapolation, 1 figure that if this bike turned 7800 rpm in top gear, it would reach a speed of about 135 mph. The only reason I can see for this drop is, possibly, wind resistance.

(Continued on Page 50)

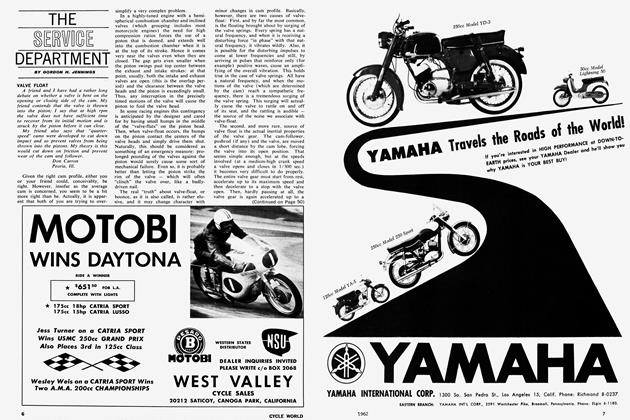

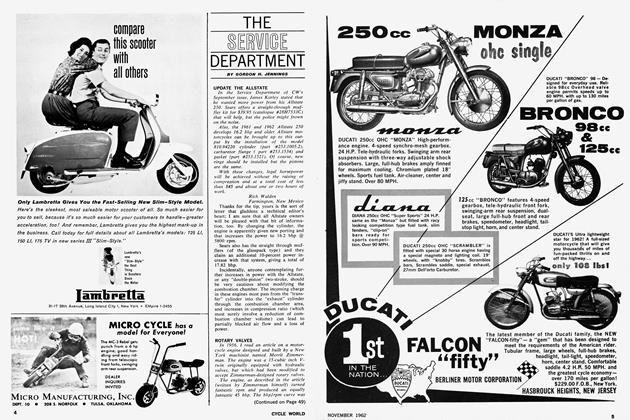

The drop is also apparent in the Bultaco TSS, Mot obi C atria, H-D Sprint, BMW R-69S and the Yamaha YD-3. Yet, in the Honda CB 77, Maico, Greeves, Triumph, Matchless and BSA motorcycles also tested in your magazine the rpm reached in fourth gear was just as high as those in the other gears.

Also, in the February issue, the top speed of the BSA Catalina is listed at 83 mph, while the best run is said to be 110 mph. I cannot understand how this is possible, unless you are using a different model — such as the Clubman — for the best run speed. Kevin Kuluvar

We cannot understand that 110 mph for the BSA Catalina, either. Somebody goofed, because an astronomical number of rpm would be needed to get the Catalina up to that speed with the gearing our test bike had. It was, plain and simply, an error.

As for the others, there are good reasons for everything. The bikes that would not pull, in top gear, the maximum engine speed listed for the lower gears do so simply because they either have power peaks well below their maximum speeds, or because they are pulling such high top gears that their engines cannot get up to their potential maximums. With overall gearing set strictly for top speed, the engine’s peaking speed should coincide with the bike’s top speed. In engines that will exceed their peaking speeds without breaking anything or experiencing valve-float, the speeds in gears can be somewhat higher — in terms of rpm — than are attainable on level ground in fourth.

Other machines may have power peaks very near the engine’s maximum speed, or gearing selected for acceleration, and these bikes will reach the safe maximum in top gear. In the case of the G-50 CSR Matchless, the top speed stated is absolute, since anything faster places the engine in considerable danger of an explosion. Others, such as the BSA Catalina, are in similar circumstances. Their top speeds are set by the safe maximum for the engine. This will be true of almost any scrambler, due to the gearing they have.

Sometime in the near future, we will present an article on gearing and how it affects performance. Look for it. •