TECHNICALITIES

GORDON H. JENNINGS

OIL COMPANIES OFTEN Involve themselves in activities not directly related to oils, or gasoline. Shell Oil Company’s research department, for example, has developed and patented a compound that cuts piston ring break-in time by about 90-percent. The Shell break-in compound is an abrasive, and literally lap-fits rings in their cylinders. Of course, this is a favorite trick of “shady-tree” mechanics when new rings arc reluctant to scat in old glazed bores, and it does work. Unfortunately, the abrasive introduced into the cylinders will wash down into the sump with the oil, and it therefore also lap-fits such things as crank journals and bearings—a not so desireable effect.

Shell’s chemists have simply eliminated this unfortunate side effect. Their abrasive is an oil-soluble chromium salt, which the user mixes with his engine's fuel supplyin proportions of about 2 grams per gallon of gasoline. It is introduced into the cylinders with the fuel, and any that finds its way down to the sump dissolves in the hot oil. In that way, the rest of the engine is protected against its abrasive effects.

Shell also compounds racing oils, and at this year's Isle of Man TT races, a lot of competitors were using Shell’s castor-base Super-M. This racing oil is intended primarily as a crankcase lubricant for 4-strokc engines, but works very nicely in 2-strokes as well. The fast and reliable Yamaha GP racing machines are Shell Super-M lubricated, and one important point I have noted is that this oil burns cleaner than some other castor-base lubricants. Pistons from the Yamaha RD56 (the GP machine) engine, and those l have seen removed from Yamaha International's (Yamaha's American importer) Racing Team TD-lBs, have all been very clean, with minimal gum and varnish deposits.

These observations made me quite curious about Shell’s Super-M, and 1 wanted to give the stuff a try in my own Yamaha TD-1B. hut wanting and getting are different things. Shell Super-M is not available from one's local friendly Shell service station, and it was not until I met a Mr. Lew Filis, Shell’s Racing Supervisor, that a supply became available. Shell, and Few Filis, were very accommodating and arranged to have a sample supply sent to C'vci r: WORLD’S offices. It should be understood that this was not just a special favor to me; Shell's entire racing department has shown itself to he ultra-obliging to all those in the racing fraternity, motorcycle or automobile, and racing would be much the worse if this kind of support was lacking. So, run right out and buy some Shell gasoline, or a can of X-100 oil, and show some appreciation of Shell’s contribution to the sport. You will also be getting a good oil. Shell’s Rotella 20W40 (a heavy-duty mineral oil) has contributed materially to the remarkable reliability of the Matchless flattrack machine Jim Nicholson rides with such effectiveness.

And now for the “Facts We Wish We Didn't Know" department. As some of you may recall, Benelli made quite a splash at the beginning of the 1965 season by outfitting their 250cc “four” with disc brakes on the front wheel. At the time, we noted that the Benelli dual-disc brakes used Airheart calipers, and that the entire setup was remarkably like that made by MotoTFC and used by Jody Nicholas on his road racing motorcycles. In point of fact, not only was the Benelli disc brake similar, it was a MotoTFC unit, sold to Benelli in January of (his year. Bo Gehring, of MotoTFC, tells us that Benelli then made more of these units in their own shops, using calipers purchased from Airheart. and he is more than a little unhappy because Benelli never acknowledged the original source of the brakes. Certainly, nowhere in the British or Furopcan press did we find a hint that the brakes were American in origin.

Apart from Bcnelli's intent in this matter, their failure to give due credit may, in the end. do them harm. MotoTFC, for example, would be most reluctant to lend further assistance! except perhaps through Bcnelli's American distributing organization. Cosmopolitan Motors, which has quite a good reputation for fair dealings.

Anyone who has tried to make a Honda Hawk go fast will be aware that one of the problems is excess weight. A standard Super Hawk, at the curb and readv to ride, tips the scales at about 350 pounds and with an engine output of 27 bhp the bike has a power to weight ratio of 13 lb/bhp. Cut 100 lbs from that, and the weight/power ratio becomes 9.3:1. To get the same effect with engine modifications, you would need almost 38 bhp, and while trimming 100 pounds from a Honda Hawk is not easy, it will be very much less a struggle than getting 38 bhp—and not nearly so expensive.

Continued on Page 12

continued

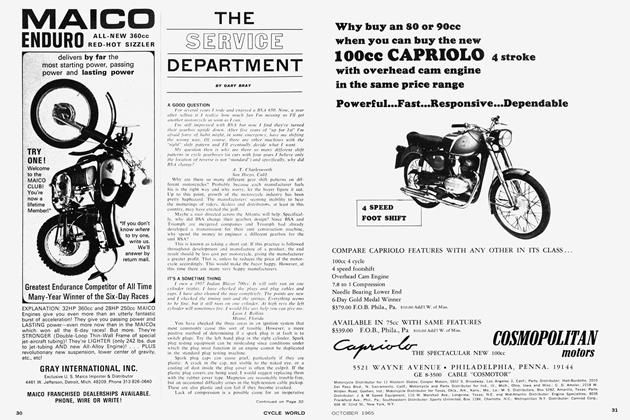

With this weight factor in mind, an item called the “Yetman Motorcycle Kit" takes on considerable significance. This kit, produced by the Autodynamics Corporation in Marblehead, Connecticut, consists of a frame, tank and fenders, all to suit Honda Hawk components. The tank and fenders are molded of fiberglass, and the tank has a capacity of 5.5 gallons. Both these items fit any Honda Hawk.

Actually, the interesting thing about the Yetman kit is the frame, which is one of the few existing examples of a “pure” space-frame applied to a motorcycle. By “pure,” I mean one in which the frame tubes are all straight, and all loads applied to the tubes are in tension, torsion or compression. The frame’s designer obviously appreciates the fact that tubes are not very efficient in carrying beam loads, and such loads have been avoided in the layout.

Good design practice is also evident in the use of mild-steel tubing, and lowtemperature welding. The tubing is all Vs" in diameter, with 20-gauge wall thickness. The welds are made with a Hutectic high

nickel alloy rod, which is more nearly brazing than welding. The Hutectic rod flows at a temperature below that of the melting point for steel, but gives an exceedingly good bond and will form a nice fillet. Joints made with this rod are much stronger than those resulting from ordinary welding, particularly in their resistance to fatigue breaks.

The Yetman frame follows the pattern of the Honda frame to the extent that the engine serves as a strut between the swingarm pivot and the steering head. Krom that point, however, all similarity stops. Where the standard Honda frame is essentially a single, large diameter “backbone” tube, the Yetman layout consists of a series of triangles and tetrahedrons. To this, you bolt-on the standard Honda swing-arm, forks, rear suspension spring/ damper units, etc. The weight of the Yetman frame is said by the makers to be under 9 pounds, which would seem to be entirely realistic considering the tube sizes and gauge involved.

What is not so realistic, to me at least, is the claim that an “all out racing machine of under 200 pounds” is possible. Assuming that we are still discussing the Honda Hawk engine, etc., I would be very much surprised if the curb weight of the YetmanHonda was much below 250 pounds, and that would be without a fairing. My Honda-Cotton weighed 281 pounds, ready to go, and 1 cannot imagine how 81 pounds could have been pared away—even if 1 had substituted a frame weighing less than nothing. 1 would have to see the Yetman-Honda on the scales to be convinced about that under-200 lb. business.

Still, there can be little doubt that the Yetman frame brings with it a substantial weight advantage, and it is worth consideration for that reason if no other. I do think, if 1 may be permitted to draw conclusions of what may be seen in photographs, that insufficient attention has been given the area around the swing-arm pivot. Side loads applied at the wheel are greatly multiplied by the time they reach the pivot, and deflections at the pivot are likewise multiplied hack at the wheel. Consequently, pivotal deflections in the micro-inch range create a noticeable wiggle at the rear wheel. Perhaps I am being too pessimistic about this point in the Yetman frame; if not, it is a thing that could be corrected fairly easily, and the basic frame is certainly a nice piece of design work.

Continued on Page 14

continued

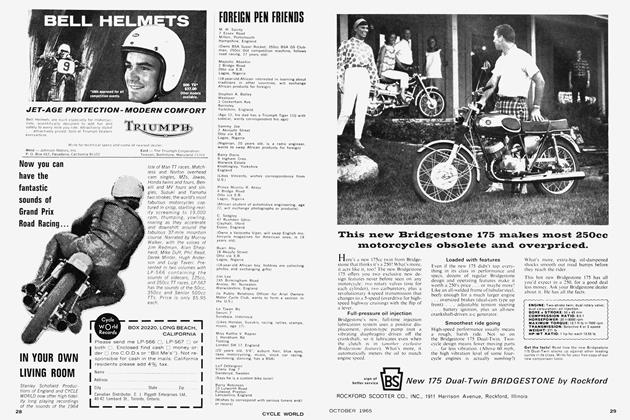

A partly amusing, partly disgusting bit of business occurred during practice for the 1965 TT races. Phil Read borrowed teammate Mike Duff's helmet, and was flagged in by the officials when it was discovered that it w'as Read and not Duff under the hat. The reason for the official frown was that England’s ACU (their equivalent of our AMA) will not permit British riders to use any but ACU-approved helmets, and Duff’s hat does not meet with ACTJ approval. Curious indeed, for Duff wears a Bell 500TX, which is by any rational standard far superior to the traditional British “porridge-pots.”

Evidently, even Read thinks that the Bell full-coverage helmet may offer some advantages. He borrowed Duff’s helmet just to see how he liked it — and he has since obtained a Bell 500TX of his own. Presumably, he will be able to wear it in continental events, but not while in England. Duff, being a Canadian, is allowed to wear the Bell helmet because they are approved wear in Canada. At one point during his career, Duff allowed himself to he talked out of wearing the Bell and at his first Grand Prix wearing a porridge-pot, he came a cropper and collected a concussion in the process. Duff says he had done substantially the same thing before, wearing the Bell, and had walked away without even a headache. It would he difficult, now, to convince Duff that the lighter and more stylish porridge-pot is worth its dashing appearance. Subjective evidence, to be sure, hut anyone who looks into the matter will find a convincing case for our American “Space-man” helmets, and most of the British racing car drivers are wearing such hats. A prominent American head-injury researcher when asked about the protective qualities of the typical porridge-pot, said that the buyer might be well advised to discard the helmet and wear the box in which it is delivered. The remark w'as intended to be humorous, but had its basis in fact. Many’s the true word spoken in jest.

A learned friend, an engineer working in two-stroke design and development, tells me about a long series of tests made with intake valve systems that have produced some interesting and enlightening results. Not too surprisingly, the disc-type rotary valve now being used on virtually all racing two-stroke engines shows a clear superiority in terms of maximum power. What is less expected was that the reedtype valve represented an improvement over the piston-controlled inlet port. Actually, at any given optimum engine speed, the piston-port arrangement gives results very similar to those obtained with reedvalves, hut the latter gives a much broader spread of power. So, with the reed-valves, overall performance is substantially improved — especially when specific power output is high and there is a limited number of transmission ratios.

In addition, with the typical reed-valve arrangement where the flow is directed straight into the crankcase, and not through the cylinder base, rod bearing life is improved. In effect, the reed-valve makes it possible to aim the incoming mixture, which carries with it the engine’s lubricating oil, directly at the connecting-rod journal. That will of course insure a maximum amount of the total percentage of oil in . the fuel reaching the heavily loaded big-end hearing.

The final advantage of the reed-valve system is that it leaves the back of the cylinder available for additional transfer ports. This would aid the transfer phase and add to both power and efficiency. In all, the net gain available from a good reed-valve setup should he considerable and I wonder how long it will he before we see the reed-valve applied to 2-stroke motorcycle engines. Reed-valves have been widely used in American outboard marine engines, and in those scandalously-fast “kart” engines. Whatever problems might have been encountered in the development of reed-valves have long since been solved, and they do look very attractive in terms of overcoming the high-output two-stroke’s tendency toward an ever-narrowing power hand. •