THE SERVICE DEPARTMENT

GORDON H. JENNINGS

RIGHT-FOOTED?

I wonder if you could answer a question that has been bothering me for months.

As it happens, I ride an old 1940 Indian 45, that has the foot brake on the right. A few months ago, a friend let me ride his machine, which has a foot brake on the left and as I came in for a landing, although going quite slow, I took a nice little spill, for no reason at all except that I pushed the wrong pedal with the wrong foot.

Since then, I have been trying to find out from someone just why any kind of a vehicle, particularly a motorcycle, would have a foot brake on the left side? Almost anyone who drives anything has been conditioned through the years to have a fast brake reflex on the right foot. However, 1 know there must be a good reason, and 1 don’t know it just because I don’t know all the facts. But, I don’t know any other riders who do either.

It does seem, though, that the positioning of the foot pedal, as unimportant as it may seem, can and does affect the entire motorcycle industry. 1 have a friend, who is fairly well off and became a motorcycle enthusiast recently. He bought three new motorcycles. None was his ideal; he bought them only because the foot brake was on the right, where he is used to having it and where he doesn’t have to think before applying it.

All of us here look forward to some kind of an answer that we hope makes sense in an early issue of your splendid magazine.

R. L. Cridland Del Mar, California

You ask for “some kind of answer” and by golly that’s what you’re getting!

To the best of my knowledge, the only reason for so many motorcycles having the brake pedal on the left is because the British started doing it that way and everyone else followed. And, as a matter of fact, there was a reason for the British taking that approach. They ride on the ledt side of the road, as everyone knows, and when waiting to make a right turn at an intersection, it is natural for the rider to lean his machine to the right, dropping his right foot to the ground. With the brake located on the left, he can then keep the brake on, to hold the machine on a hill, with his free foot.

Our staff members are not greatly bothered by the differences in brake location; we have been conditioned, by the vast number of road test machines that pass through our hands, to be fairly adaptable. We did worry about this factor at first. but small emergencies met and properly dealt with have proved that when the chips are down, we unerringly go for the correct pedal. However, this facility is the product of long conditioning, and we recognize that this is not available to all riders. And, in point of fact, we are entirely in favor of standardization: all

motorcycles, like all cars, should have the brake pedal on the same side. To have it otherwise is to invite disaster. Further, we would really like to see all brake pedals located on the right side of the bike, for the very reason you outlined in your letter: people are accustomed to reaching for the brake with their right foot, and there seems to be little point in asking them to develop new reflexes — which might very well fail them in a pinch.

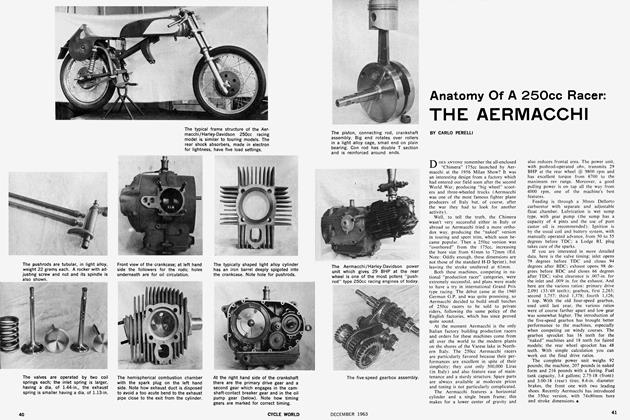

THE SUPER, SUPER HAWK

As a Super Hawk owner, 1 was very interested in CYCLE WORLD’S article on the Forged-true 350cc kit. As a guide to us who will make the conversion, would you publish the spark setting, plug heat range and carburetor jets which gave the best results on your test cycle?

Has any brave soul ascertained the top speed of that machine?

The production clutch is somewhat marginal, even in a stock Super Hawk, and the 350cc owner will certainly want to beef his up. A perfectly sanitary (and very simple) way is to use ordinary split washers (lock washers) to shim each clutch spring. Only one or two will be needed for each spring. Use the same number on each spring, of course, and as few as will do the job; greatly excessive spring tension will distort or break the pressure plate.

Kent Salzman

Kingston, Tennessee

Thank you for your suggestions regarding the Honda clutch. We have had no trouble with clutches on either the stock or modified Honda, but it is entirely possible that someone might, and in that event the shimming of the springs is an acceptable means of increasing clutch torque capacity. A better method is to add plates; but that is quite often not possible without a radical reworking.

We should have mentioned in the article on the 350 kit, but did not, that after all of the fiddling with jets had been done, we found ourselves right back with the stock jets. As for spark-plug heat range, we used NGK “9” plugs, but the standard heat range would be correct for all-around street riding. The ignition setting was also standard.

It is worth mentioning that Tony Murphy uses the standard ignition advance setting on the 350-conversion Honda Hawk he runs in road races. Murphy says that the engine does not appear to be at all sensitive to changes in ignition advance. He also says that he uses an NGK 14 plug for both warm-up and racing (the 350-kit has oil rings that do the job) and that no problems with fouling have occurred. Jetting, for the road racer, varies with conditions, but more often than not 170-175 jets give the best results.

(Continued on Page 8)

No top speed runs were made with the Forgedtrue Honda, but we did have an opportunity to check Tony Murphy’s machine. It has a road racing-type fairing, which helps reduce wind resistance, and its top speed was in excess of 120 mph. It seems very probable that a stock 350equipped Super Hawk, with the right gearing, would get up to around 112 mph.

TECHNICAL ANNUAL?

/ am wondering, as are probably many other of your readers, if CYCLE WORLD intends or has considered publishing an annual or semiannual compilation of technical articles that have appeared in CYCLE WORLD.

1 myself would like to purchase either a hard paperback or clothback book just such as this.

Perhaps there is not a big enough demand here in the States for books written to cover all machines, but I’d be willing to bet they’d sell if someone took the trouble to write them, instead of reprinting outdated material.

Gary D. Christenson Seattle, Washington

Yes indeed! We have given some thought to publishing a technical annual — and a sporting model road test annual. The former would be, as you say, a compilation of technical articles we have published in the past, except that there would be some updating done; the latter would be a similar book, but containing our road tests of the outstanding motorcycles of the past couple of years.

Quite frankly, we do not know how well received these books would be. Things of this sort have merit, as they centralize information that would otherwise be sprinkled throughout an entire armload of magazines. Perhaps some of our readers would like to drop us a post card giving their thoughts on the matter.

NSU-WANKEL

Some months ago l read a report in an automotive magazine which stated that the NSU works, in Germany, was tinkering with an odd little powerplant which involved a triangular piston which revolved, rather than reciprocated. The report indicated that the little 30 bhp dingus, installed in a 4-wheeled insect called the “Wankel,” was performing quite well and seemed to have distinct advantages over conventional engines: such as lightness, minute size, efficiency, etc.

At present there is a tremendous clamor about turbine engines and the prospective application of same in cars. They, too, seem to have advantages over the mundane piston engine; but of these two, I would prefer the Wankel engine.

I wish to know if any cycle manufacturer is planning to install either type of engine in their machine? I do not wish to see the motorcycle industry trapped in the bonds of custom.

William Lay Palatka, Florida

Periodically, throughout the long history of the reciprocating-type, internal combustion engine, someone has announced a “revolutionary” new approach that was to sweep conventional engines away into oblivion. These new designs always sound great, and they always disappear into the oblivion they had reserved for the conventional engines that have served us all so well.

The new engine to which you have reference is the NSU-Wankel, designed by a German named Wankel and developed under the direction and with the resources of NSU. Actually, the Wankel engine has a trochoidal chamber, in which a 3-lobe rotor works. The rotor is geared to a shaft, and the shaft runs at 3-times rotor speed. Compression and expansion cycles are provided as the rotor works in and out of the corners of the trochoidal (actually, epitrochoidal, but let’s not get complicated) chamber. The rotor’s motions are partly rotary, and partly from side to side.

The ends of the rotor are flat, as are the ends of the chamber, and flat steel sealing-strips are fitted in the rotor to prevent blow-by. Similar sealing-strips are fitted in the rotor tips. Careful design and development work has produced seals that will hold the gas pressure; but no solution has been found to the problem of wear. The rotor speed is quite high, and the seals must be copiously lubricated to get reasonable wear rates. And, with enough oil to prevent rapid wearing of the seals, there is excessive oil consumption — this being the historical Achillesheel of rotary engines.

NSU has developed the Wankel engine to a point where they apparently feel that it is time it went into production, and this engine will be available in their small sports car in 1964.

Many advantages have been claimed for the NSU-Wankel, small size and weight, with high power-output, among them, but in reading through the various engineering reports that have come my way since the engine development program was announced some 5 years ago, I conclude that in its final form, the Wankel engine is really not any better than the conventional piston-type engine. And, the problems with seal lubrication and wear have not, even at this late date, been solved.

Turbine engines are great: vibrationless, light, and powerful. Unfortunately, they lack flexibility, have poor throttle response, and are extremely expensive. Do not expect to see them in general use, outside the trucking business, for several years.

The motorcycle industry is not trapped by the bonds of custom. Rather, it is limited by what is practical, now, and by what the customer is willing to pay.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue