SIDECAR RACING

The most spectacular form of motorcycle road racing has to be seen to be believed.

TONY HOGG

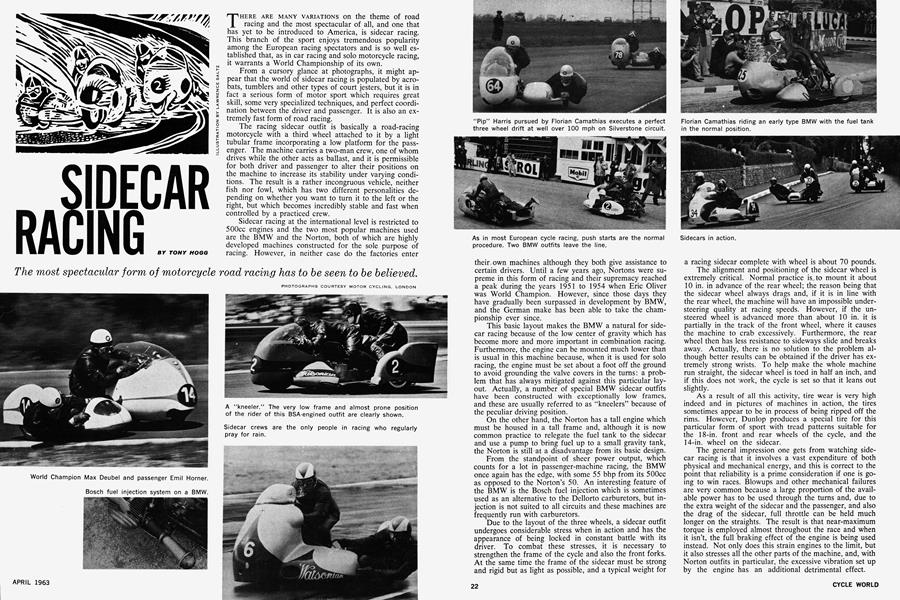

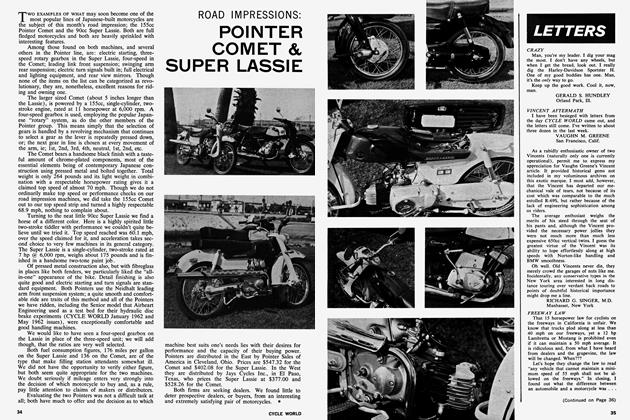

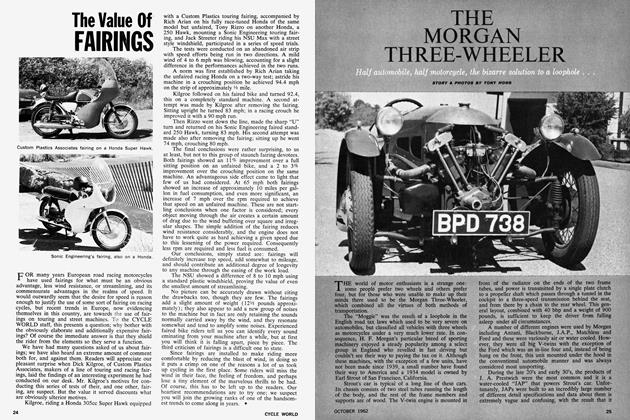

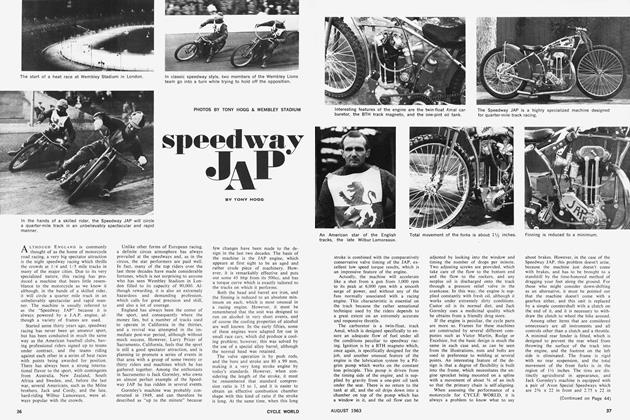

THERE ARE MANY VARIATIONS on the theme of road racing and the most spectacular of all, and one that has yet to be introduced to America, is sidecar racing. This branch of the sport enjoys tremendous popularity among the European racing spectators and is so well established that, as in car racing and solo motorcycle racing, it warrants a World Championship of its own. From a cursory glance at photographs, it might appear that the world of sidecar racing is populated by acrobats, tumblers and other types of court jesters, but it is in fact a serious form of motor sport which requires great skill, some very specialized techniques, and perfect coordination between the driver and passenger. It is also an extremely fast form of road racing.

The racing sidecar outfit is basically a road-racing motorcycle with a third wheel attached to it by a light tubular frame incorporating a low platform for the passenger. The machine carries a two-man crew, one of whom drives while the other acts as ballast, and it is permissible for both driver and passenger to alter their positions on the machine to increase its stability under varying conditions. The result is a rather incongruous vehicle, neither fish nor fowl, which has two different personalities depending on whether you want to turn it to the left or the right, but which becomes incredibly stable and fast when controlled by a practiced crew.

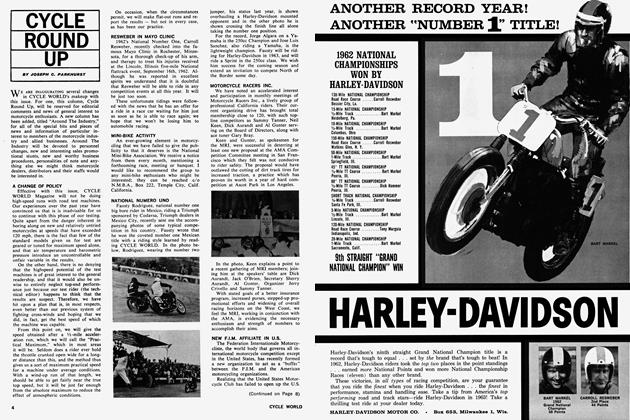

Sidecar racing at the international level is restricted to 500cc engines and the two most popular machines used are the BMW and the Norton, both of which are highly developed machines constructed for the sole purpose of racing. However, in neither case do the factories enter starts are the normal procedure. Two BMW outfits leave the line.</pam:caption> <p>their, own machines although they both give assistance to certain drivers. Until a few years ago, Nortons were supreme in this form of racing and their supremacy reached a peak during the years 1951 to 1954 when Eric Oliver was World Champion. However, since those days they have gradually been surpassed in development

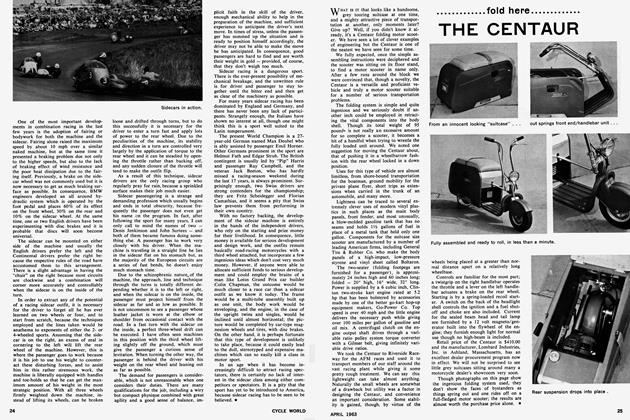

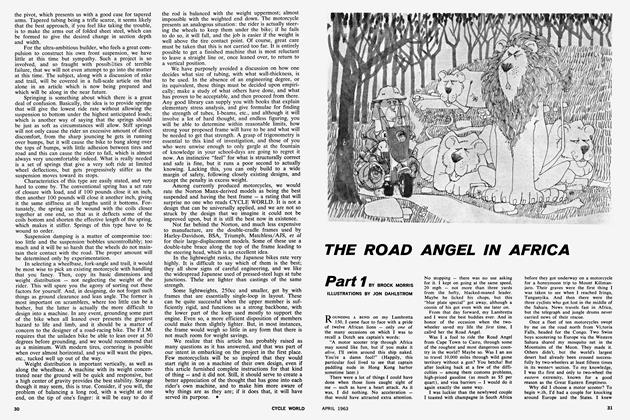

by BMW, and the German make has been able to take the championship ever since.</p> <p>This basic layout makes the BMW a natural for sidecar racing because of the low center of gravity which has become more and more important in combination racing. Furthermore, the engine can be mounted much lower than is usual in this machine because, when it is used for solo racing, the engine must be set about a foot off the ground to avoid grounding the valve covers in the turns: a problem that has always mitigated against this particular layout. Actually, a number of special BMW sidecar outfits

have been constructed with exceptionally low frames, and these are usually referred to as “kneelers” because of the peculiar driving position.</p> <p>On the other hand, the Norton has a tall engine which must be housed in a tall frame and, although it is now common practice to relegate the fuel tank to

the sidecar and use a pump to bring fuel up to a small gravity tank, the Norton is still at a disadvantage from its basic design.</p> <p>From the standpoint of sheer power output, which counts for a lot in passenger-machine racing, the BMW once again has the edge, with some 55 bhp from its 500cc as opposed to the Norton’s 50. An interesting feature of the BMW is the

Bosch fuel injection which is sometimes used as an alternative to the Dellorto carburetors, but injection is not suited to all circuits and these machines are frequently run with carburetors.</p> <p link_para="22.2">Due to the layout of the three wheels, a sidecar outfit undergoes considerable stress when in action and has the appearance of being locked in constant battle with its driver. To combat these stresses, it is frame of the sidecar must be strong and rigid but

as light as possible, and a typical weight for</p> <pam:caption check_zone="true">Florian Camathias riding an early type BMW with the fuel tank in the normal position.</pam:caption> <pam:caption check_zone="true">Sidecars in action.</pam:caption> <p link_para="22.2">a racing sidecar complete with wheel is about 70 pounds.</p> <p>The alignment and positioning of the sidecar wheel is extremely critical. Normal practice is to mount it about 10 in. in advance of the rear wheel; the reason being that the sidecar wheel always drags and, if it is in line with the rear wheel, the machine will have an impossible understeering quality at racing speeds. However, if the unsteered wheel is advanced more than about 10 in. it is partially in the track of the front wheel, where it causes the machine to crab excessively. Furthermore, the rear wheel then has less resistance to sideways slide and breaks

away. Actually, there is no solution to the problem although better results can be obtained if the driver has extremely strong wrists. To help make the whole machine run straight, the sidecar wheel is toed in half an inch, and if this does not work, the cycle is set so that it leans out slightly.</p> <p>As a result of all this

activity, tire wear is very high indeed and in pictures of machines in action, the tires sometimes appear to be in process of being ripped off the rims. However, Dunlop produces a special tire for this particular form of sport with tread patterns suitable for the 18-in. front and rear wheels of the cycle, and the 14-in. wheel on the sidecar.</p> <p article_con="22.1">The general impression one gets from watching sidecar racing is that it involves a vast expenditure of both physical and mechanical energy, and this is correct to the point that reliability is a prime consideration if one is going to win races. Blowups and other mechanical failures are very common because a large proportion of the available power has to be used through the turns and, due to the extra weight of the sidecar and the passenger, and also the drag of the sidecar, full throttle can be held much longer on the straights.

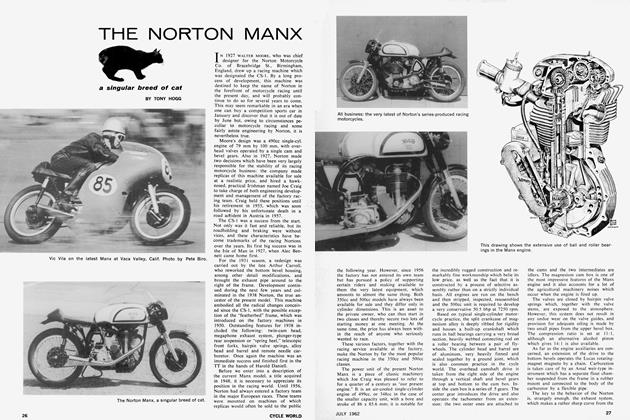

One of the most important developments in combination racing in the last few years is the adoption of fairing or bodywork for both the machine and the sidecar. Fairing alone raised the maximum speed by about 10 mph over a similar naked machine, but at the same time it presented a braking problem due not only to the higher speeds, but also to the lack of braking effect of wind resistance and the poor heat dissipation due to the fairing itself. Previously, a brake on the sidecar wheel was not commonly used but it is now necessary to get as much braking surface as possible. In consequence, BMW engineers developed an all around hydraulic system which is operated by the foot pedal and places 60% of its effect on the front wheel, 30% on the rear and 10% on the sidecar wheel. At the same time, one or two English drivers have been experimenting with disc brakes and it is probable that discs will soon become universal.

The sidecar can be mounted on either side of the machine and usually the English drivers prefer the left and the Continental drivers prefer the right because the respective rules of the road have accustomed them to this arrangement. There is a slight advantage in having the “chair” on the right because most circuits are clockwise and a combination will corner more accurately and controllably when the sidecar is on the inside of the turn.

In order to extract any of the potential of a racing sidecar outfit, it is necessary for the driver to forget all he has ever learned on two wheels or four, and to start from scratch, because the techniques employed and the lines taken would be anathema to exponents of either the 2or 4-wheeled sports. Assuming that the sidecar is on the right, an excess of zeal in cornering to the left will lift the rear wheel of the machine. However, this is where the passenger goes to work because it is his job to use his weight to counteract these disturbing forces, and to assist him in this rather strenuous work, the machine is liberally equipped with handles and toe-holds so that he can get the maximum amount of his weight in the most strategic position. With all three wheels firmly weighted down the machine, instead of lifting its wheels, can be broken loose and drifted through turns, but to do this successfully it is necessary for the driver to enter a turn fast and apply lots of power to the rear wheel. Due to the peculiarities of the machine, its stability and direction in a turn are controlled very largely by the application of torque to the rear wheel and it can be steadied by opening the throttle rather than backing off, and any sudden closure of the throttle will tend to make the outfit flip.

As a result of this technique, sidecar drivers are the only racing group who regularly pray for rain, because a sprinkled surface makes their job much easier.

Sidecar passengering is a strange and demanding profession which usually begins and ends in total obscurity, because frequently the passenger does not even get his name on the program. In fact, after following the sport for many years, I can only call to mind the names of two — Denis Jenkinson and John Surtees — and both of them became famous doing something else. A passenger has to work very closely with his driver. When the machine is traveling in a straight line he lies in the sidecar flat on his stomach but, as the majority of the European circuits are a series of fast bends, he doesn’t enjoy much stomach time.

Due to the schizophrenic nature, of the machine, the approach, line and technique through the turns is totally different depending whether it is to the left or right, and when the sidecar is on the inside, the passenger must project himself from the sidecar as far and as low as possible. It is not uncommon to see a passenger whose leather jacket is worn at the elbow or shoulder from occasional contact with the road. In a fast turn with the sidecar on the inside, a perfect three-wheel drift can be executed. I have often seen machines in this position with the third wheel lifting slightly off the ground, which must give the passenger a curious sense of levitation. When turning the other way, the passenger is behind the driver with his weight on the rear wheel and leaning out as far as possible.

The demand for passengers is considerable, which is not unreasonable when one considers their duties. There are many qualifications for the job, including a wiry but compact physique combined with great agility and a good sense of balance, implicit faith in the skill of the driver, enough mechanical ability to help in the preparation of the machine, and sufficient experience to anticipate the driver’s next move. In times of stress, unless the passenger has summed up the situation and is ready to position himself accordingly, the driver may not be able to make the move he has anticipated. In consequence, good passengers are hard to find and are worth their weight in gold — provided, of course, that they don’t weigh too much.

Sidecar racing is a dangerous sport. There is the ever-present possibility of mechanical breakage, and the unwritten rule is for driver and passenger to stay together until the bitter end and then get as clear of the machinery as possible.

For many years sidecar racing has been dominated by England and Germany, and there has never been any lack of participants. Strangely enough, the Italians have shown no interest at all, though one might think this is a sport well suited to the Latin temperament.

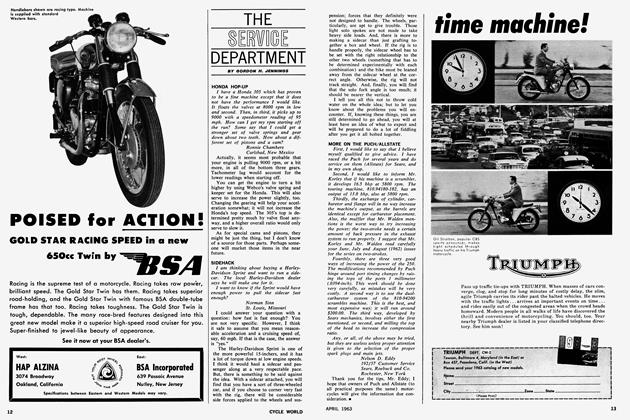

The present World Champion is a 27year-old German named Max Deubel who is ably assisted by passenger Emil Horner. Other Germans prominent in the sport are Helmut Fath and Edgar Strub. The British contingent is usually led by “Pip” Harris and passenger Ray Campbell, and the veteran Jack Beeton, who has hardly missed a racing-season weekend during the last 17 years, is always prominent. Surprisingly enough, two Swiss drivers are strong contenders for the championship; they are Fritz Scheidegger and Florian Camathias, and it seems a pity that Swiss law prevents them from performing in their own country.

With no factory backing, the development of the sidecar machine is entirely in the hands of the independent drivers, who rely on the starting and prize money for their livelihood. In consequence, little money is available for serious development and design work, and the outfits remain basically road-racing motorcycles with a third wheel attached, but incorporate a few ingenious ideas which don’t cost very much money. However, if anyone were able to allocate sufficient funds to serious development and could employ the brains of a man like Lotus Grand Prix car builder Colin Chapman, the outcome would be much closer to a race car than a sidecar outfit as we know it today. The frame would be a multi-tube assembly built up as one unit, the body work would be enveloping, and the engine, in the case of the upright twins and singles, would be inclined until almost horizontal; the picture would be completed by car-type magnesium wheels and tires, with disc brakes. On the other hand, it is perhaps fortunate that this type of development is unlikely to take place, because it could easily lead to the dull, stereotyped and expensive machines which can so easily kill a class in motor sport.

In an age when it has become increasingly difficult to attract racing spectators, there is certainly no lack of interest in the sidecar class among either competitors or spectators. It is a pity that the sport has yet to be introduced to America, because sidecar racing has to be seen to be believed. •

View Full Issue

View Full Issue