THE MORGAN THREE-WHEELER

Half automobile, half motorcycle, the bizarre soluion to a loophole...

TONY HOGG

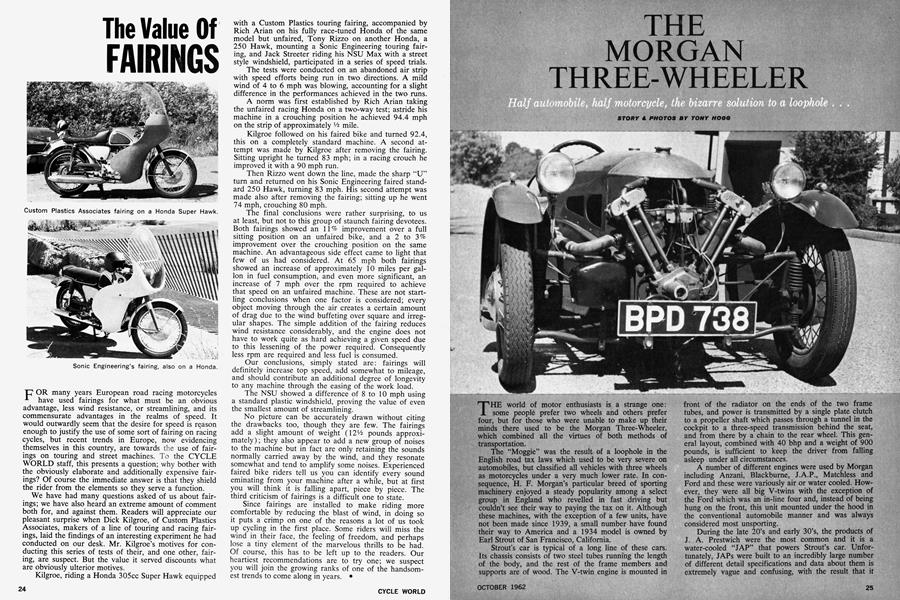

THE world of motor enthusiasts is a strange one: some people prefer two wheels and others prefer four, but for those who were unable to make up their minds there used to be the Morgan Three-Wheeler, which combined all the virtues of both methods of transpotation.

The “Moggie” was the result of a loophole in the road tax laws which used to be very severe on but classified all vehicles with three wheels as motorcycles under a very much lower rate. In consequence, H. F. Morgan’s particular breed of sporting machinery enjoyed a steady popularity among a select group in England who revelled in fast driving but couldn’t see their way to paying the tax on it. Although these machines, with the exception of a few units, have not been made since 1939, a small number have found their way to America and a 1934 model is owned by Strout of San Francisco, California.

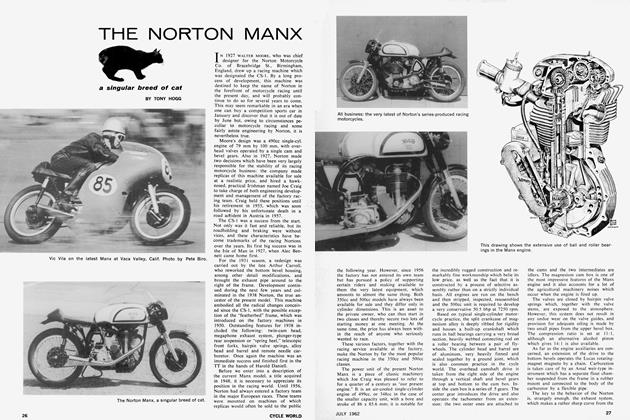

Strout’s car is typical of a long line of these cars. Its chassis consists of two steel tubes running the length of the body, and the rest of the frame members and are of wood. The V-twin engine is mounted in front radiator on the ends of the two frame tubes, and power is transmitted by a single plate clutch to a propeller shaft which passes through a tunnel in the cockpit to a three-speed transmission behind the seat, and from there by a chain to the rear wheel. This general layout, combined with 40 bhp and a weight of 900 pounds, is sufficient to keep the driver from falling asleep under all circumstances.

A number of different engines were used by Morgan including Anzani, Blackbume, J.A.P., Matchless and Ford and these were variously air or water cooled. However, they were all big V-twins with the exception of the Ford which was an in-line four and, instead of being hung on the front, this unit mounted under the hood in conventional automobile manner and was always considered most unsporting.

During the late 20’s and early 30’s, the products J. A. Prestwich were the most common and it is a water-cooled “JAP” that powers Strout’s car. Unfortunately, JAPs were built to an incredibly large number of different detail specifications and data about them is extremely vague and confusing, with the resuit that it is impossible to give accurate technical information about this particular unit. However, it is a water-cooled twin of l,100cc giving 40 bhp. The valves are operated by long pushrods and the combustion chambers are hemispherical in the normal motorcycle manner.

Engine lubrication is by a dry sump system from an oil tank situated under the hood, but Strout’s car has been modified so that a cycle oil tank is slung from one of the front suspension supports to the right of the engine. The valve springs and rockers are open to the atmosphere, which reminded me of a 300 mile trip I once took in England in a “Moggie” which was admitting too much oil to its valve guides. This, in conjunction with a broken windshield, resulted in me arriving at my destination almost entirely black from the chest up.

Carburetion is by a single Amal fitted with two float chambers to ensure an even level of gas during cornering, because otherwise this instrument will dry up due to centrifugal force, and the fuel is supplied by gravity from a tank under the hood. Contrary to normal cycle practice, ignition is by coil and distributor.

Fitted to the engine shaft is a flywheel which accepts an automobile type single plate clutch. The flywheel carries a ring gear for the electric starter but, despite an exhaust valve lifter control, the only way to start a Morgan is with the crank, because it seems that 60 degree V-twins and starter motors just aren’t in sympathy.

The drive is taken from the clutch by a propeller shaft to the transmission situated just behind the seat. For some strange reason, there are no universal joints in this shaft and in consequence the engine has to be very carefully aligned with shims when replacing, and periodic realignment is necessary because the frame has a tendency to sag after a period of time. The transmission is a three-speed unit with a worm on the end of the mainshaft which engages with a worm wheel to take the drive through 90 degrees, and a sprocket on the worm wheel delivers the drive by chain to the rear wheel. On the opposite side of the transmission to the chain sprocket is a pulley which drives the generator, so the battery is not being charged unless the car is actually in motion.

After it has become worn, the transmission has a tendency to engage two gears at once, which happen to be first and reverse, with the result that all forward motion ceases instantly. However, an advantage of the Morgan is that one can then lift up the rear end of the car, wheel it to the side of the road, and effect the necessary repairs with the minimum amount of delay and embarrassment.

In 1911, H.F.S. Morgan designed a system of independent front suspension which incorporated sliding stub axles and it is the same basic design which is used in Morgan cars today. At the rear, the wheel is carried on two arms pivoted at the transmission and supported by two quarter elliptic springs and, in general, the suspension is extremely hard indeed. Furthermore, it is not softened very much by the 4.00 x 18 tires all-round.

The braking system is peculiar because the foot pedal operates a brake on the rear wheel which has to be applied with considerable discretion or the wheel will lock, and the front brakes are applied by the emergency brake lever. This, of course, is pure cycle practice and does not present much of a problem once one has experienced the effect of each individual system and can tailor one’s braking to the needs of the moment. Both systems are cable operated and require much stronger pressures than are normal today.

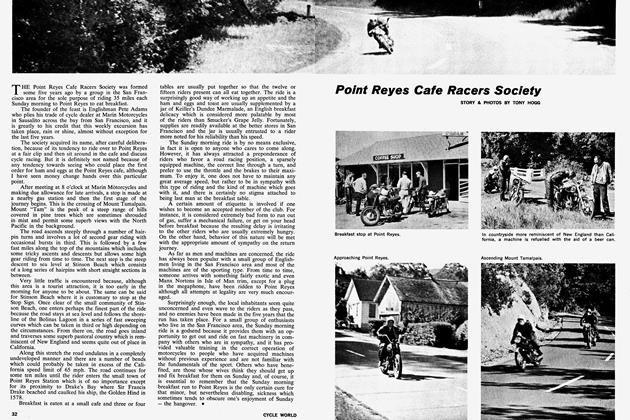

The cockpit of the car is comfortable, but cramped when a passenger is carried, and one has to be careful to avoid the hot exhaust pipes which run along each side of the body. The controls are laid out in the conventional manner except that the throttle, air and ignition controls are situated on the steering wheel and, in consequence, a well-educated thumb is required to accurately control the engine speed when shifting, although this becomes surprisingly easy after a short spell at the wheel. The steering is extremely quick with 3/4 turn from lock to lock and is also very heavy, but the heaviness disappears as soon as the car is in motion.

To start the engine is quite easy provided one knows the correct setting for the controls for a particular car. The throttle must be opened a little and it is essential to retard the ignition because these big twins have a kick like a mule. In cold weather, it is necessary to choke the engine and flood the carburetor, but after making these preliminary settings, the motor will usually fire after two or three sharp pulls on the crank. The idle is very steady and slow and each beat of the engine can be felt through the car. This slow idle is due in part to the fact that the normal flywheels inside the crankcase are assisted by the outside flywheel and automobile type clutch, all of which contribute to the flywheel effect. This arrangement also has a bearing on the low speed torque of the car, which is surprisingly good.

First gear engages quite easily although, if the alignment of the engine is not true, considerable clutch drag will be experienced. The car moves away without fuss provided the throttle opening is increased slightly as the clutch is engaged, and the road speed can be taken up to 25 mph before shifting into second. Second is good for between 40 and 45 mph and after making the shift into high, a pleasant cruising speed will be found in the 60-65 mph range and a maximum of 80 mph is attainable.

As far as road holding is concerned, the car is greatly affected by the road surface and, while it is quite comfortable and steady on freeways, it tends to jump around all over the road on an uneven surface. This is due in part to a tendency for the rear wheel to bounce, causing the car to steer with both ends at the same time. However, the extremely quick steering is useful in correcting these deviationist tendencies once one has become used to it, and the machine as a whole presents quite a challenge to one’s driving skill if the best performance is to be gotten out of it.

A family automobile business, which has existed on a minor and specialist scale for over fifty years, is a rarity. H.F.S. Morgan died in 1959 and left it to his son Peter who is well equipped to carry on the traditions of the Morgan company. The current Morgans still have an independent front suspension based on the old man’s design and a considerable amount of timber is included with every car. Totally unconcerned with mergers, takeover bids and other financial wizardry, Peter Morgan calmly goes about his business of building limited production sports cars and enjoys a fair degree of prosperity from his labors.

During a recent conversation with him, I asked if he planned a return to the Three-Wheeler and he pointed out that it was no longer necessary to make them because of a relaxation of'the English road tax. However, after renewing my acquaintance with one of these vehicles, the possibility of a four-wheeled sports car using a big V-twin cycle engine slung on the front is an intriguing one, particularly to those people who are cycle enthusiasts at heart. For sheer simplicity, accessibility and low manufacturing costs it seems to be a natural for any manufacturer who has some big V-twins to spare, so how about it up there in Milwaukee?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle Round Up

OCTOBER 1962 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Service Department

OCTOBER 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

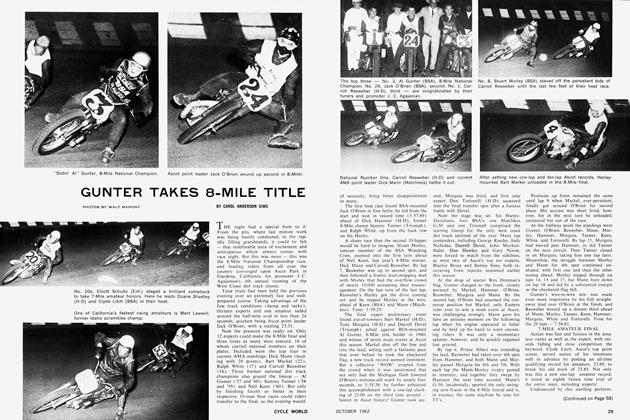

Gunter Takes 8-Mile Title

OCTOBER 1962 By Carol Anderson Sims -

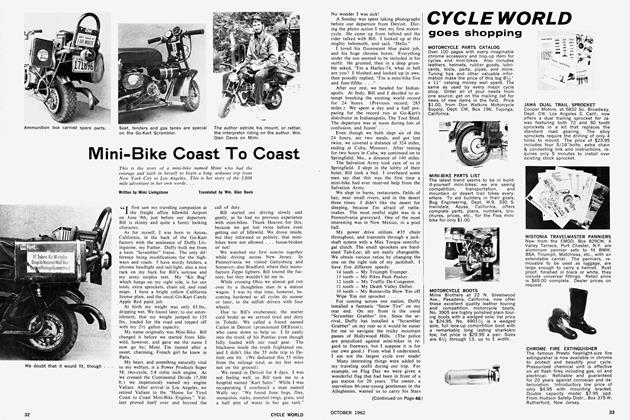

Mini-Bike Coast To Coast

OCTOBER 1962 By Mimi Livingstone -

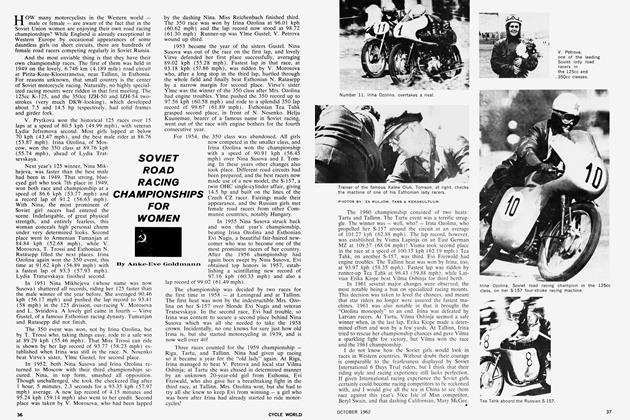

Soviet Road Racing Championships For Women

OCTOBER 1962 By Anke-Eve Goldmann -

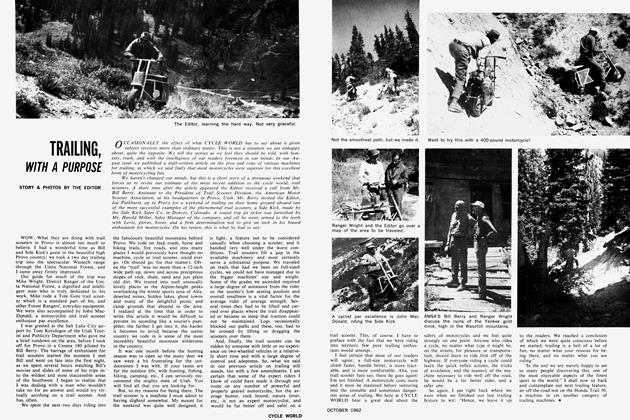

Trailing, With A Purpose

OCTOBER 1962