MOTOBI 175 CATRIA

Cycle World Road Test

SOMETIMES, the performance capabilities of lightweight, small-displacement motorcycles are so good that we wonder why so many “big” bikes are on the road. Certainly, the performance potential does not go up in direct proportion to increases in engine displacement and there are limits to the amount of speed one may use in any case. Go too fast and you may find yourself explaining your transgressions to a law officer. That is one of the reasons why the lightweights are such fun to ride; you may extend them to the limit and go flailing down the road for all they’re worth—and never get going fast enough to break any laws (well, maybe bend them a bit). Whatever the reasons, we like the tiddlers.

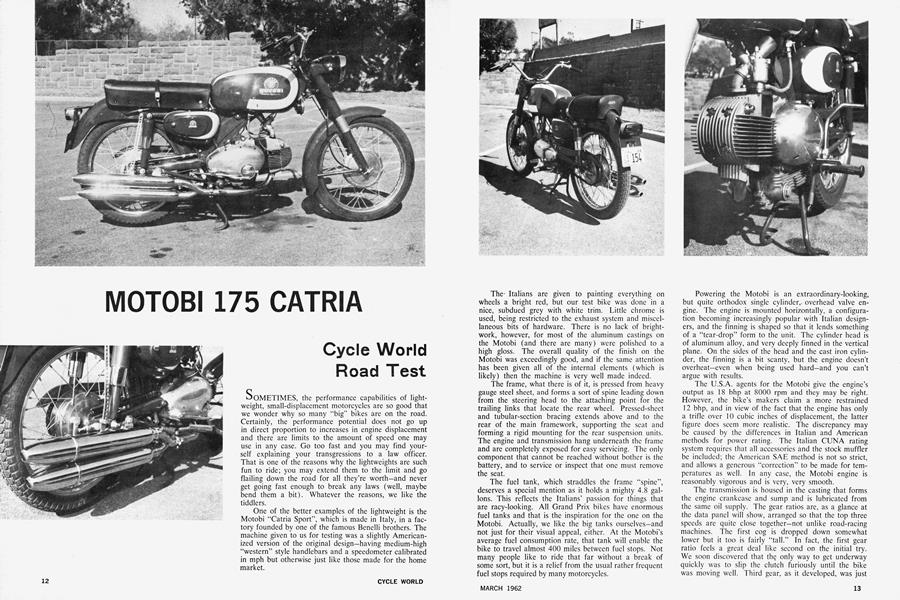

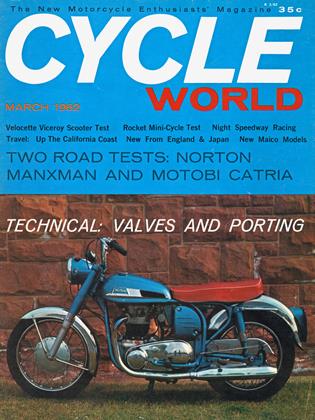

One of the better examples of the lightweight is the Motobi “Catria Sport”, which is made in Italy, in a factory founded by one of the famous Benelli brothers. The machine given to us for testing was a slightly Americanized version of the original design—having medium-high “western” style handlebars and a speedometer calibrated in mph but otherwise just like those made for the home market.

TheItalians are given to painting everything on wheels a bright red, but our test bike was done in a nice, subdued grey with white trim. Little chrome is used, being restricted to the exhaust system and miscellaneous bits of hardware. There is no lack of brightwork, however, for most of the aluminum castings on the Motobi (and there are many) were polished to a high gloss. The overall quality of the finish on the Motobi was exceedingly good, and if the same attention has been given all of the internal elements (which is likely) then the machine is very well made indeed.

The frame, what there is of it, is pressed from heavy gauge steel sheet, and forms a sort of spine leading down from the steering head to the attaching point for the trailing links that locate the rear wheel. Pressed-sheet and tubular-section bracing extends above and to the rear of the main framework, supporting the seat and forming a rigid mounting for the rear suspension units. The engine and transmission hang underneath the frame and are completely exposed for easy servicing. The only component that cannot be reached without bother is the battery, and to service or inspect that one must remove the seat.

The fuel tank, which straddles the frame “spine”, deserves a special mention as it holds a mighty 4.8 gallons. This reflects the Italians’ passion for things that are racy-looking. All Grand Prix bikes have enormous fuel tanks and that is the inspiration for the one on the Motobi. Actually, we like the big tanks ourselves—and not just for their visual appeal, either. At the Motobi’s average fuel consumption rate, that tank will enable the bike to travel almost 400 miles between fuel stops. Not many people like to ride that far without a break of some sort, but it is a relief from the usual rather frequent fuel stops required by many motorcycles.

Powering the Motobi is an extraordinary-looking, but quite orthodox single cylinder,, overhead valve engine. The engine is mounted horizontally, a configuration becoming increasingly popular with Italian designers, and the finning is shaped so that it lends something of a “tear-drop” form to the unit. The cylinder head is of aluminum alloy, and very deeply finned in the vertical plane. On the sides of the head and the cast iron cylinder, the finning is a bit scanty, but the engine doesn’t overheat—even when being used hard—and you can’t argue with results.

The U.S.A. agents for the Motobi give the engine’s output as 18 bhp at 8000 rpm and they may be right. However, the bike’s makers claim a more restrained 12 bhp, and in view of the fact that the engine has only a trifle over 10 cubic inches of displacement, the latter figure does seem more realistic. The discrepancy may be caused by the differences in Italian and American methods for power rating. The Italian CUNA rating system requires that all accessories and the stock muffler be included; the American SAE method is not so strict, and allows a generous “correction” to be made for temperatures as well. In any case, the Motobi engine is reasonably vigorous and is very, very smooth.

The transmission is housed in the casting that forms the engine crankcase and sump and is lubricated from the same oil supply. The gear ratios are, as a glance at the data panel will show, arranged so that the top three speeds are quite close together—not unlike road-racing machines. The first cog is dropped down somewhat lower but it too is fairly “tall.” In fact, the first gear ratio feels a great deal like second on the initial try. We soon discovered that the only way to get underway quickly was to slip the clutch furiously until the bike was moving well. Third gear, as it developed, was just about as fast as fourth. The overall ratio proved to be a bit too ambitious for the engine, loading it down to a modest 6800 rpm at the bike’s top speed. A higher ratio would have been useful for our speed trials but the stock gearing did enable the Motobi to* hold a good, brisk 60 mph cruising speed without feeling as though it was going to burst.

Touring on the Motobi, while pleasant, would have been a lot more comfortable if the seat had not been so narrow. Just one more inch of width would have done wonders, we are sure. The seating position, relative to the pedals and handlebars, could hardly have been improved upon and the controls were both light and precise in action. We especially liked the rocker-type gearshift pedal, which enables the rider to really ram those shifts home—going up through the gears or coming down.

Another point of comfort, although it is not often thought of as such, was the easy starting of the Motobi. There was some early reluctance, before we found the right combination, but after a time it began to crank-off for us, hot or cold, with very little hesitance. The kickstart pedal was mounted on the left-a feature we do not normally like—but we soon discovered that with such a small engine it was possible to stand beside the machine and use the right leg for kicking it through. Actually, though, the force required to pump the engine over is so little that there was never any problem-either right or left “footed.”

Braking, even on a lightweight, is an important factor and those on the Motobi were equal to any conceivable combination of load and/or speed. No matter what, the Motobi’s stoppers are going to bring the machine and whatever it happens to be carrying to a quick halt. The brakes are large, have aluminum drums and are very light in action. They would be very difficult to improve upon.

The creation of good-handling, fast-cornering machinery seems to be a special talent of the Italians, and they have not failed us in the case of the Motobi. On first inspection, the idea of cornering vigorously on those narrow-section tires is a trifle unsettling. But, as experience demonstrated, any fears we had were groundless. The Motobi will lean into bends, fast or slow, with the best of them and if these fine little machines don’t win a few road races here in America, it won’t be because of any deficiencies in their ability to get through the turns quickly.

At low speeds, threading our way through the “boondocks”, we were pleased to find that the Motobi had considerable merit there, too. A lot of steering lock has been provided and this feature makes the bike extremely agile. The lack of super-traction tires and the gearing, which is unsuited to dirt riding, handicapped the Motobi out in the rough, but we were left with the impression that one of these machines, suitably modified, could be a real dandy in scrambles and cross-country events. Ground clearance would be a small problem, but there is nothing vulnerable hanging down—aside from the castaluminum sump, which appears to be sturdy enough to take nearly anything.

Taken by and large, the Motobi 175 is a very good small-class motorcycle. It is not as fast, in a straight line, as some of the more imaginatively engineered creations one sees these days, but it certainly is no sluggard and it does offer an uncommonly fast, strain-free cruising speed. It also offers a large measure of stability, outstanding brakes and impressive cornering qualities. To top it all, the finish is so good that only a very picayune-ish person is likely to find fault. If you like the little bikes (and we are willing to admit that we do) don’t miss any chance you may have to try the Motobi; it is a real little gem. •

MOTOBI

CATRIA

SPECIFICATIONS

$569

POWER TRANSMISSION

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle Round Up

MARCH 1962 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Service Department

MARCH 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

Technical

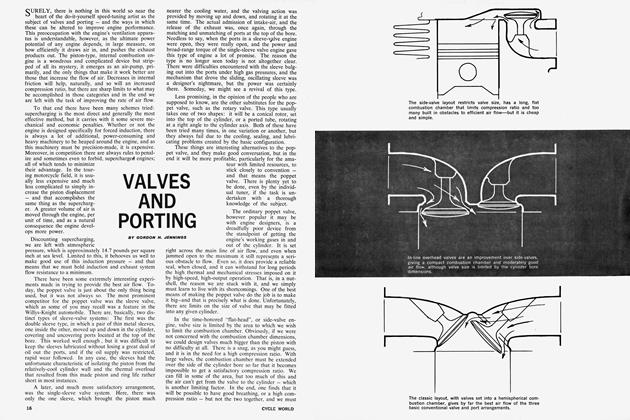

TechnicalValves And Porting

MARCH 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

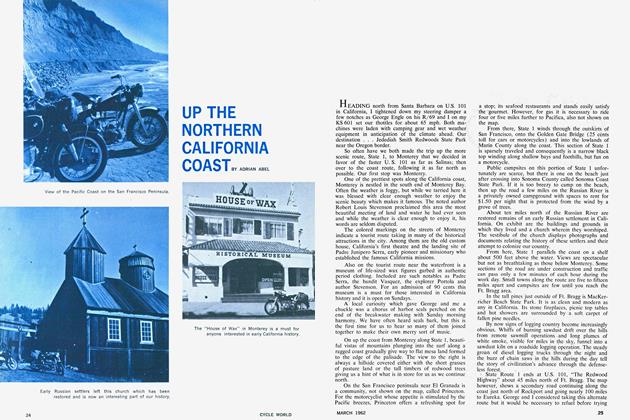

Travel

TravelUp the Northern California Coast

MARCH 1962 By Adrian Abel -

A Progress Report

A Progress ReportCycle World Forges Ahead

MARCH 1962 By Joe Parkhurst -

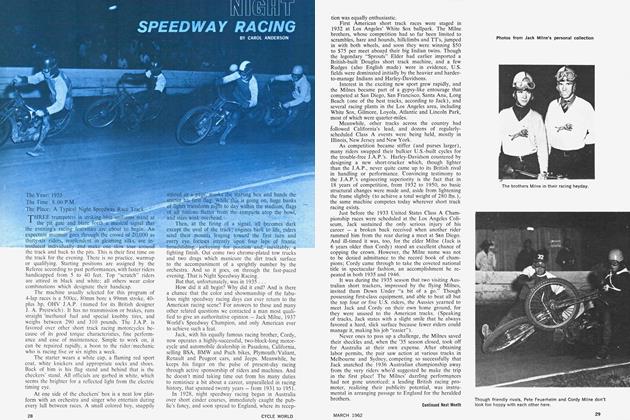

Night Speedway Racing

MARCH 1962 By Carol Anderson