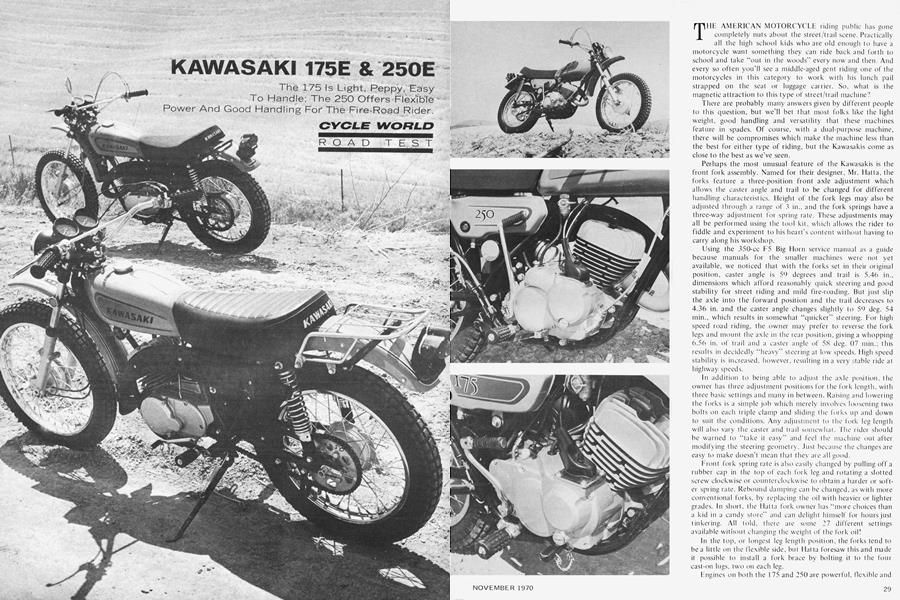

KAWASAKI 175E & 250E

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

The 175 Is Light, Peppy, Easy To Handle; The 250 Offers Flexible Power And Good Handling For The Fire-Road Rider.

THE AMERICAN MOTORCYCLE riding public has gone completely nuts about the street/trail scene. Practically all the high school kids who are old enough to have a motorcycle want something they can ride back and forth to school and take “out in the woods" every now and then. And every so often you'll see a middle-aged gent riding one of the motorcycles in this category to work with his lunch pail strapped on the seat or luggage carrier. So, what is the magnetic attraction to this type of strect/trail machine?

There are probably many answers given by different people to this question, but we'll bet that most folks like the light weight, good handling and versatility that these machines feature in spades. Of course, with a dual-purpose machine, there will be compromises which make the machine less than the best for either type of riding, but the Kawasakis come as close to the best as we've seen.

Perhaps the most unusual feature of the Kawasakis is the front fork assembly. Named for their designer, Mr. llatta, the forks feature a three-position front axle adjustment which allows the caster angle and trail to be changed for different handling characteristics. Height of the fork legs may also be adjusted through a range of 3 in., and the fork springs have a three-way adjustment for spring rate. These adjustments may all be performed using the tool kit, which allows the rider to fiddle and experiment to his heart’s content without having to carry along his workshop.

Using the 350-cc F5 Big Horn service manual as a guide because manuals for the smaller machines were not yet available, we noticed that with the forks set in their original position, caster angle is 59 degrees and trail is 5.46 in., dimensions which afford reasonably quick steering and good stability for street riding and mild fire-roading. But just slip the axle into the forward position and the trail decreases to 4.36 in. and the caster angle changes slightly to 59 deg. 54 min., which results in somewhat “quicker" steering. For high speed road riding, the owner may prefer to reverse the fork legs and mount the axle in the rear position, giving a whopping 6.56 in. of trail and a caster angle of 58 deg. 07 min.; this results in decidedly “heavy" steering at low speeds. High speed stability is increased, however, resulting in a very stable ride at highway speeds.

In addition to being able to adjust the axle position, the owner has three adjustment positions for the fork length, with three basic settings and many in between. Raising and lowering the forks is a simple job which merely involves loosening two bolts on each triple clamp and sliding the forks up and down to suit the conditions. Any adjustment to the fork leg length will also vary the caster and trail somewhat. The rider should be warned to “take it easy" and feel the machine out after modifying the steering geometry. Just because the changes are easy to make doesn't mean that they are all good.

Front fork spring rate is also easily changed by pulling off a rubber cap in the top of each fork leg and rotating a slotted screw clockwise or counterclockwise to obtain a harder or softer spring rate. Rebound damping can be changed, as with more conventional forks, by replacing the oil with heavier or lighter grades. In short, the llatta fork owner has “more choices than a kid in a candy store" and can delight himself for hours just tinkering. All told, there are some 27 different settings available without changing the weight of the fork oil!

In the top, or longest leg length position, the forks tend to be a little on the flexible side, but llatta foresaw this and made it possible to install a fork brace by bolting it to the four cast-on lugs, two on each leg.

Engines on both the 175 and 250 are powerful, flexible and easy to start. Our 175 had as much low-end power as some 250s. Die-cast aluminum engine cases are featured and are well finished and strong. A rotary inlet valve is used, as on most of Kawasaki’s machines, and five transfer ports allow the fuel/air charge to move from the crankcase to the combustion chamber. Both bikes exhibited a slight rattle from the ultra-thin rotary valve, but such a valve is needed if engine width is to be kept at a minimum, an important consideration on a trail machine.

Two spark plug holes are tapped into the cylinder head which allows the owner to carry a spare spark plug or install a compression release for increased engine braking. In typical two-stroke fashion, the crankshaft is a pressed-together affair, with the rod running on roller bearings at the big end and needle bearings at the wrist pin. Hefty ball bearings support the crankshaft in the cases, and a gear drive to the clutch is used.

Clutches were light in action and very positive in taking up the drive, but both tended to drag just enough to make neutral selection difficult when the machine was stationary. Selecting neutral while rolling obviated this malady, but was inconvenient at times.

The five-speed transmissions are of constant-mesh design and use three conventional shifter forks riding in a grooved shifting drum. Ball and roller bearings support both the layshaft and the mainshaft, and the gears are all of generous dimensions to ensure reliability. Shifting was light and easy, but it was possible, particularly with the 250, to shift through second and third gears into an unwanted neutral il care was not exercised. The Kawasaki F-5 Big Horn we tested in the January 1()7() issue suffered from the same problem, but since both of our test bikes in this issue were prototypes, and the I 75 was quite new and still tight, it is possible that the shifting would improve when the machines become fully broken in.

Ignition and lighting on both bikes were faultless, although the horns of both ceased operating after a few minutes of operation, indicating a need for some detailing to ward off the effects of vibration. Nonetheless, the system is simple and the components are well made.

Three coils are located inside the flywheel, which contains the magnets. These coils are the primary and secondary ignition coils and the lighting coil which supplies alternating current to the rectifier (which changes the a.c. current to d.c.) to operate the lights and horn and to charge the battery. Due to the differences in output required for day riding with the lights off, when the output required is light, and for night riding with the lights on, when more current is required, a light load wire and a heavy load wire are taken from the lighting coil and are connected to the main switch.

The 1 75 had several new features which we especially liked. New rubber hoods are mounted on the speedometer and tachometer, and the dials are black with pale green numerals and red-tipped white pointers. Controls are laid out conventionally, and the clutch and brake levers on both bikes now come with rubber dust excluders like their bigger brother, the Big Horn. High mounted front fenders reduce the unsprung weight of the front wheel and prevent the building up of mud between the front wheel and the fender. Both bikes feature folding footpegs that are adjustable for height, and a rear chain guide which is invaluable when riding through brush. The 175 had chains between the brake and gearshift pedals and the frame to prevent the accumulation of sticks and brush. We assume that the 250s will come similarly equipped, as ours was an early prototype which was slightly different from the production models.

Kawasaki’s effective Superlube automatic oil injection system is featured on both bikes, which precludes mixing the gas and oil separately. Oil is fed from the oil pump through the inlet tract and directly into the crankcase where it lubricates the bearings and cylinder wall. The more the throttle is opened and the higher the crankshaft speed, the more oil that is delivered to the engine.

A vacuum fuel valve is located under the tank on the 175 which opens when there is a vacuum in the inlet manifold. Hence, there is no worry about shutting the fuel off at night or when the machine is left standing. There is a reserve position and a prime position to flood the carburetor if the bike has been left standing for a long period of time. We hope the production 250s will have the same feature.

The 175 has a drain pump like the Big Horn, which operates by crankcase pressure using one-way valves to pump out any excess gasoline at the bottom of the carburetor chamber, while the 250 utilizes a one-way valve beneath the carburetor cavity to perform the same function.

Floating rear brake plates are a professional touch on both machines, which, until recently, were found only on some motocross machines. The brake anchor is bolted under the swinging arm pivot to minimize the torque effect, which tends to “lift” the swinging arm when the rear brake is applied and cause the rear wheel to hop excessively when braking on rough surfaces. Five-way adjustable rear shock absorbers with good rebound damping also help keep wheel hop to a minimum on the 250. The 175 is not as well off, however, and the back wheel can be made to chatter vigorously in rapid stops on the dirt, suggesting an inappropriate damping rate. Muffling is excellent and the silencing units are equipped with an approved spark arrestor. Both pipes are finished in heatresisting matt black paint, and the rider’s leg is protected by a huge metal heat shield.

The 250 has slightly larger brakes and stronger wheels to cope with its heavier weight, but both machines’ brakes were firm and predictable. It is reassuring when you can clamp on a front brake in the dirt and don’t have to worry about the front wheel locking up and depositing you on the ground; and they worked quite well on the street, too, with their cast aluminum lips to exclude water.

Frame design is almost identical to the F5 Big Horn with duplex downtubes running from the steering head down under the engine and circling back up to connect with the double top backbone tubes. A large, single tube connects the top of the steering head with the back section. Steel plates are welded to the frame and serve as a rigid mount for the swinging arm. This adds much to the stable handling qualities inherent in the main frame section. Bash plates between the bottom tubes protect the engines’ undersides from rocks and logs.

Even with the suspension completely dialed in, the bikes weren’t the best handling dirt bikes we’ve ever ridden, but this fault can undoubtedly be alleviated somewhat by stripping off some of the unnecessary (for trail riding) electrical gear and reducing the overall weight. With ultra-comfortable seats, comfortable handlebars and a good relationship between the handlebars, seat and footrests, both bikes could be ridden out in the woods for long periods of time without the rider becoming unduly fatigued.

Paint and chrome plating were of typically high quality. Unfortunately, the attractive color stripe decals on the tank will bubble and peel quickly with a day’s dosage of sloshed gasoline, heat and dirt. The welds were well executed and everything we took off the bikes went right back on without having to pry or force things. It’s hard to fault automation! [Q]

KAWASAKI

175E & 250E

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

November 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

November 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

November 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Technical, Etc.

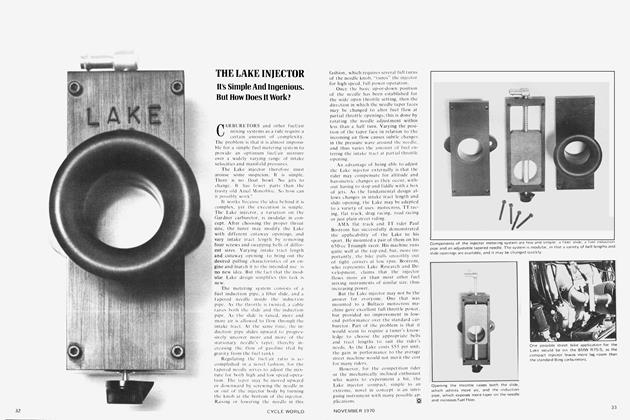

Technical, Etc.The Lake Injector

November 1970 -

Features

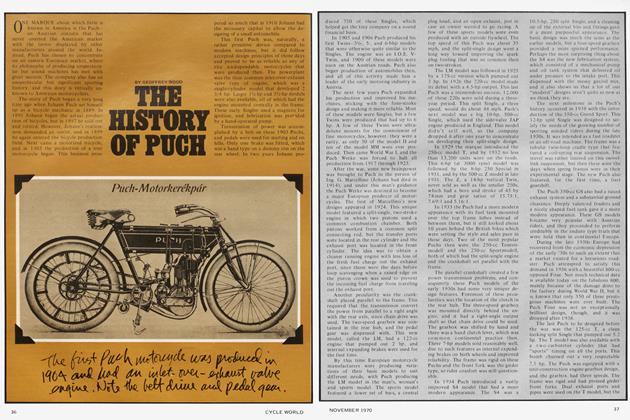

FeaturesThe History of Puch

November 1970 By Geoffrey Wood