TALES OF BRAVE ULYSSES

When Buell developed an American adventure bike

September 1 2021 STEVE ANDERSONWhen Buell developed an American adventure bike

September 1 2021 STEVE ANDERSONTALES OF BRAVE ULYSSES

ORIGINS

When Buell developed an American adventure bike

STEVE ANDERSON

It was the kind of phone call no CEO wants to get. It was to Jon Flickinger, the president of Buell Motorcycles, and it was from Gail Lione, head of Buell-owner Harley-Davidson’s legal department. The message was essentially this: “Stop your guys from top-speed testing on Interstate 43 right now! People driving to work at H-D keep telling me that they’ve been passed by bikes on Buell factory plates going about a million miles an hour.”

Tony Stefanelli, who was the platform director in charge of Buell Ulysses development, doesn’t mind sharing that story a decade and a half after the event, even if it got a little heated back in the day. He explains, “Some manufacturers at the time [cough, BMW, cough] put a speed limit on a fully loaded adventure bike with weight in the luggage: 110 mph or so. We didn’t want that. So we did a lot of testing to make sure that the bike was stable at its top speed.” There wasn’t any legal place to do quick top-speed stability tests on a new configuration near the Buell offices, so Interstate 43 it was.

While probably 20 or more people at Buell actively worked on the Ulysses development at one point or the other, the three who most shaped it were Stefanelli, Erik Buell, and John Fox, the lead design engineer for the project. Stefanelli remembers the beginning of the project: “We wanted parts commonization with other XB models to keep the cost of tooling and the overall cost down, but we needed to hit the features and specs target: ‘the most fun-to-ride adventure-touring bike.’ Given our engine, we knew we needed to emphasize the street portion, but it also had to be fun off-pavement.

Erik wasn’t shy about letting us use different triple clamps, forks, rear subframe—but he wanted to keep the same airbox and stuff.”

Fox remembers, “As we got into it, we ended up making changes to the frame, the steering-head angle, we made changes to the rear, the subframe and the shock mount location on the frame. We increased the suspension travel, lifting the bike up, and increased the luggage capacity.” Some of those choices were planned, while others weren’t anticipated

Both Stefanelli and Fox recall the first prototypes as being super tall. It wasn’t a big issue for Stefanelli, who always had at least one KTM competition enduro bike in his garage, but for somewhat height-challenged Fox, it meant he struggled to get a foot on the ground when the bike was stopped. According to Stefanelli, the solution was shortening the suspension travel a little more than an inch to get the seat height lower. “The rear cylinder head was where it was, and shortening travel was the only option.”

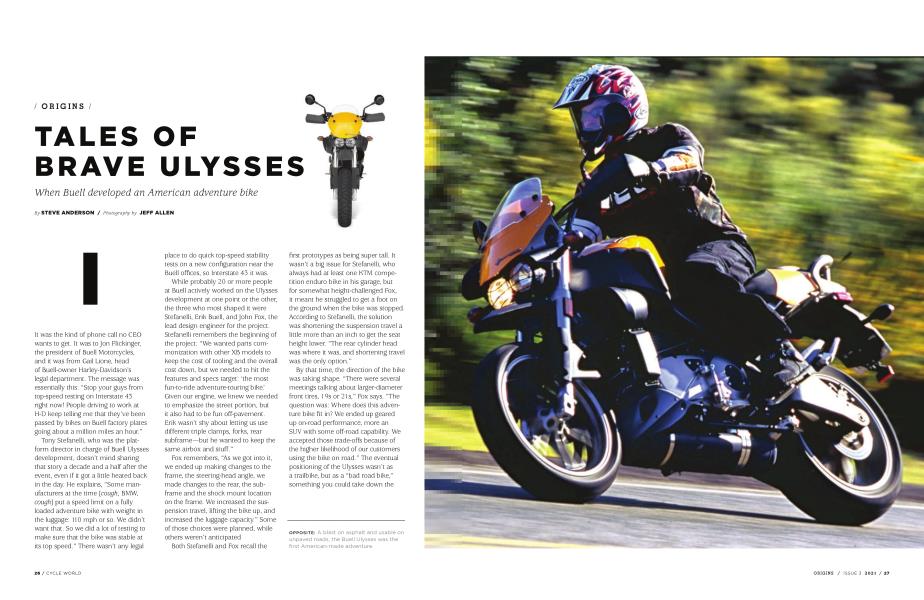

By that time, the direction of the bike was taking shape. “There were several meetings talking about larger-diameter front tires, 19s or 21 s,” Fox says. “The question was: Where does this adventure bike fit in? We ended up geared up on-road performance, more an SUV with some off-road capability. We accepted those trade-offs because of the higher likelihood of our customers using the bike on road.” The eventual positioning of the Ulysses wasn’t as a trailbike, but as a “bad road bike,” something you could take down the gnarliest asphalt or gravel road quickly and comfortably. Tires remained 17-inchers at both ends, more supermoto than dirt bike.

Stefanelli says there were places that Harley-Davidson just wouldn’t let Buell go with the Ulysses, in the kind of micromanagement that used to drive Erik Buell crazy: “Originally, it was going to be a chain final drive,” Stefanelli says. “But Harley didn’t want us doing a chain and show that there were any weaknesses in belt drives. But the Gates belts wouldn’t work off-road, getting damaged by stones or packing with mud and getting overtightened. I wanted to do openings on the sprockets to give mud or foreign objects a place to go. Gates said that wouldn’t work. The holes in the sprockets didn’t fail, but we still couldn’t get the Gates belts to work. We had to show Harley so much data that Gates wouldn’t work. Finally, we told them: It was either a chain or a Goodyear belt, what do you want? Harley said go with Goodyear.” The Goodyear belts, made of Kevlar in a rubber matrix, were much more damage resistant than the carbon-fiber-in-a-polyurethane-matrix Gates belts, even if they didn’t have the same theoretical strength. Which all goes to explain why Stefanelli was shocked when the H-D Pan America came with a chain.

I participated in the first Cycle World road test on a production Ulysses, and then a few months later went to work for Buell, the second platform director and Stefanelli’s peer. By that time the Ulysses was safely in production, with a small team of two engineers fixing problems that showed up in warranty reports and upgrading the bike as possible. The Ulysses went from Dunlop tires to Pirellis, and the steering geometry changed a bit, items that improved stability even more after first year complaints from German autobahn users. The engine became more durable, and engine heat on the rider was reduced by clever airflow management. The Ulysses was one of Buell’s better-selling models, and I had put a lot of miles on the bikes and on fleet bikes at Buell. I loved it.

“I still have my 2010 Ulysses, and not because I worked on it. It’s just fun.”

Stefanelli explains why, in part: “I still have my 2010 Ulysses, and not because I worked on it. It’s just fun. There was a GP course at the Ford Proving Ground where we tested that was halfway between a road course and an autocross course. Top speed there was probably 80 mph and the slowest corners were 20 to 25 mph. The Buell test riders thought the Ulysses was the fastest bike there, faster than an 1125. It was light and had a short wheelbase. It had a steep head angle. It would really transfer right to left quickly. The riders just raved about how fun the Ulysses was on the GP track. ”

And I still remember one of the most memorable rides of my life, which was on a Ulysses. In early 2008 Harley-Davidson’s European PR team arranged an in-Europe reintroduction of the Buell 1125 to the European press, at the Monteblanco Circuit outside of Seville, Spain. I flew over as the engineering representative from Buell. The Monteblanco Circuit was designed as a country club or off-season testing circuit. It was tight and basically consisted of short straights ending in tight corners, and was much, much more demanding on brake heat dissipation than, say, Daytona. You couldn’t have picked a worse circuit to show off the 1125, which loved fast tracks and sweepers and whose single-disc design struggled with shedding heat. Without racing pads, disc brakes literally melted in the event, something that inspired many brake improvements in later Buells.

“But while the event was a disaster for showing off the 1125, there was also a fleet of Ulysses there, and the PR types had arranged to use them on a route that included 20 or so miles of mountain road under construction. The mountain road had been graded and graveled and rolled, but was yet unpaved. Leaving the Monteblanco Circuit on the Ulysses,

I rode with Craig Jones, engineer and “Wheelie King” who was sponsored by Buell at the time, and who rode for us in some crazy French rally events that were essentially roadracing on bad public roads.

On the way to the mountain road, the Ulysses we were on tried to kill us in the few hundred meters of sand wash the PR guys had chosen as part of the route, the short trail of the Ulysses and the 17-inch front tire simply not compatible with a deep, loose sand. But then we got to the hard-pack mountain road. We let all the European journalists go ahead, the majority of them inexperienced in off-road riding. Then Craig and I attacked the road, 20 miles of mountain flat tracking. As long as you stayed on the throttle in a corner, you could do no wrong on a Ulysses. It was a magic bike on that road, a refined and street-legal XR-750, except better. We ended up passing almost everyone we had let in front of us. Bad road bike, indeed.

John Fox had similar fondness for the Ulysses: “Journalists were always complaining about the Harley engines in XBs. But I was at the Ulysses US press launch in Colorado, and we were stopped at the lunch break, and a journalist, I don’t remember who, came to me grinning big: This motor has finally found its home.’"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

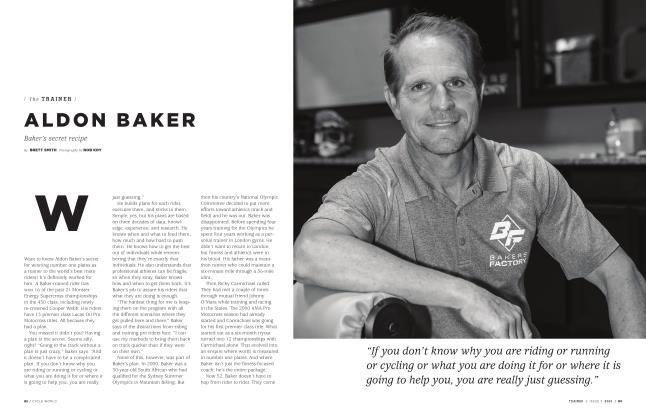

The TRAINER

The TRAINERALDON BAKER

Issue 3 2021 By BRETT SMITH -

CALIFORNIA TT

Issue 3 2021 By MICHAEL GILBERT -

TDC

TDCIN THE STYLE OF THE TIME

Issue 3 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

ELEMENTS

ELEMENTSTHE ELEGANT SOLUTIONS

Issue 3 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

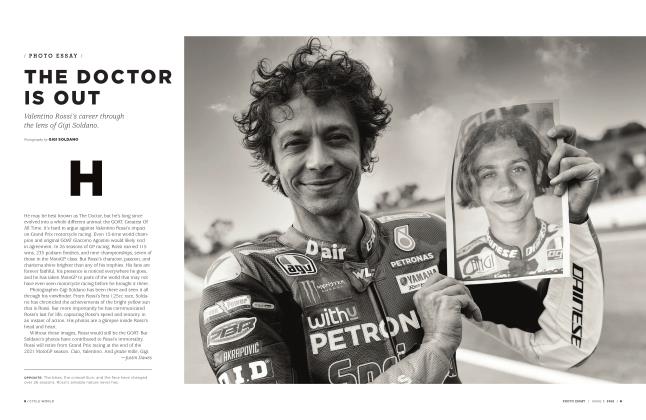

PHOTO ESSAY

PHOTO ESSAYTHE DOCTOR IS OUT

Issue 3 2021 By Justin Dawes -

UP FRONT

UP FRONTSERIES D

Issue 3 2021 By MARK HOYER