WHEN THE ENGINE STARTS

TDC

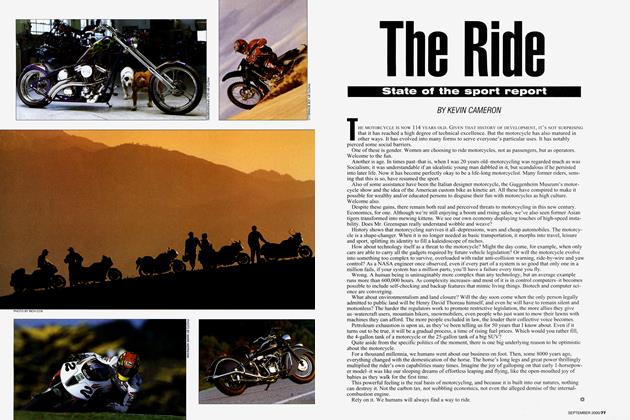

The Joy of Movement

KEVIN CAMERON

I bought a terrible rigid-framed BSA D1 Bantam for $140 in 1959. Insuring and registering anything as offensive to good order as a motorcycle in those days required that I enter the “assigned risk pool.” I took the subway there and I stood in one of the several lines. The window closed as I reached it, so I moved to another line. Eventually I had the essentials—plate and registration.

The great day came—to ride from my strange new life to my old familiar one, 200 miles up through New Hampshire and Vermont, crossing Lake Champlain at Crown Point and then into the Adirondack Park.

My little engine fussed along. In hilly Vermont, top gear (third) was inevitably too tall and second too low, so at first I oscillated. Then I found a truck just a little faster than I was, and I stuck close in his draft, feeling the alternating side-to-side buffets of whirling wake vortices shed from the box.

I wasn’t actually cold, but I certainly wasn’t warm. It was good to arrive after some 200 miles. I had escaped undetected.

Years later I was in Germany to visit Continental Tire, and my host was describing the lives of European salarymen, who know exactly how much they will be paid in each decade of their entirely predictable working lives. They know when they will be able to afford to marry. They know when they can afford a car. They are arguably prisoners on a slow-moving escalator, as perhaps I was at university.

Some of them therefore buy adventure-themed motorcycles that will never take flight off the crest of an equatorial dune or tear at 90 mph through National Geographic villages full of smiling children. The traveling machines humans make are means of possible escape. The tasks of responsible members of society become easier when they know that an engine could be started and a great journey begun. It never will, because the terms of employment must be met, the payments made, the savings wisely accumulated. But it could be. The engine could be started.

I built pipes for a man well into middle life whose anchor in a stormy sea of prescribed behaviors was a modified Kawasaki 500cc HI Triple. His family didn’t like or understand it, but he had won from them a temporary deviation. He had over the course of a season or two of club road racing gone through three sets of drag pipes: their limited cornering clearance had triggered three pipe-flattening crashes. He didn’t mind the crashes—I had the feeling he’d actually enjoyed them: they represented something totally foreign to the life around him—but he knew that family forces were marshaling to put an end to his adventure.

I built the pipes directly on his bike, tucked away so that even with suspension compressed in mid-corner and the machine at a lean angle unlikely for a clubman, they would not touch the pavement.

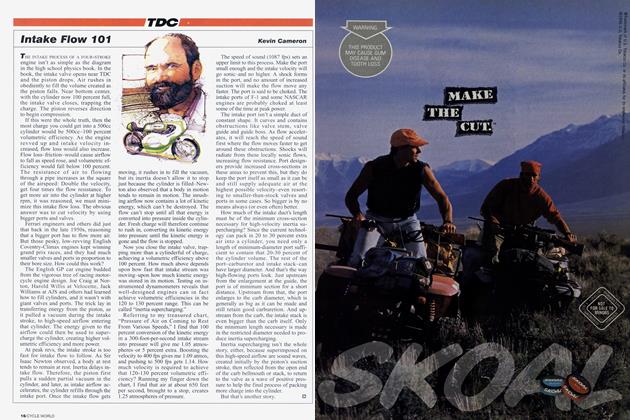

“If the engine has fuel, spark, compression, and timing, it has no choice; it will start and run. ”

Months later he phoned me to say that the elders of his family had gathered in grave conference, with the result that he was given the predictable choice. He was unable to continue racing. I had the feeling that the unspoken message was to thank someone who had taken his limited escape seriously. His family might be pillars of high tradition but he would know that he had donned leathers and helmet and raced a motorcycle.

The appetites of World War II had required that every rail locomotive in the nation work 24 hours a day— including giant coal-fired steam engines. As my family’s first postwar trip to visit grandparents was about to begin, my dad took me to the far end of the platform to see the engine, wreathed in steam and radiating heat. It was frightening but fascinating, covered with mysterious shapes and constructions that I wished I could understand.

Most tremendous were the engine’s “forearms”—the great steel driving rods that transmitted to the driving wheels the force of steam pressure on the double-acting pistons. There was the engineer, high in his cab, comfortable, even nonchalant. Soon he would move the throttle, steam would be admitted to the cylinders, and those tall steel wheels would turn.

In the spring of 1952, at Betties, Alaska, a bush pilot was about to start a high-wing Noordwyn “Norseman” floatplane. For him it was a routine departure, something he did every working day. For me, 10 years old, it was an irresistible display of the power of human devising.

The propeller blades swung slowly round, oily smoke curled from the exhaust pipes, and the start failed after a few coughs.

The pilot, looking down, reaccelerated the inertia starter’s flywheel for 30 seconds and at the second try the engine fired and cleared, blowing away a hurricane of thick smoke from oil accumulated in its cylinders. Soon he was in flight, climbing over the empty boreal forest.

As a boy, Peter Clifford—former editor of Motocourse—lived near an RAF fighter base. On any day he might see a swept-wing Mach 2 BAC Lightning aircraft make its take-off run, then pull up into a vertical climb and disappear. Who could resist such magical liberation from earth—to vanish into the zenith? Much later in life he made the flight he’d held in his imagination for years—in the back seat of a Lightning for hire in South African civil registration.

Straight up at 50,000 feet per minute (566 mph). Fuel consumption for that aircraft, in that regime of flight, is 1,050 pounds per minute.

On a pleasant fall afternoon in 1969, I sat cross-legged next to my motorcycle, near a two-lane asphalt road leading north to Bennington, Vermont. I was clearing a light piston seizure with a bit of wet-or-dry sandpaper over a forefinger. Beside me on the grass was the engine’s cylinder, already prepared for reassembly. The little kit I’d brought with me contained everything I needed to get going again.

Soon the freshly smoothed piston was back on the rod with wristpin clips in place, the cylinder was slid into place over it and its rings, and I was tightening the four head nuts. My dad had once challenged me during a previous project, “What makes you think that once you get this thing together it will even run?”

I replied that if the engine has fuel, spark, compression, and timing, it has no choice; it will start and run.

Soon I had started the engine. As it warmed, I put on a helmet and gloves. I was on my way. I felt unstoppable.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

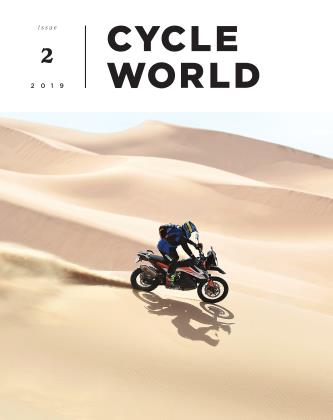

More From This Issue

-

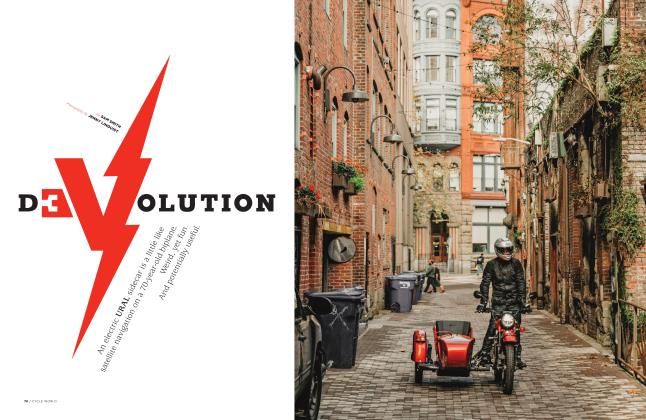

Devolution

Issue 2 2019 By Sam Smith -

Feature

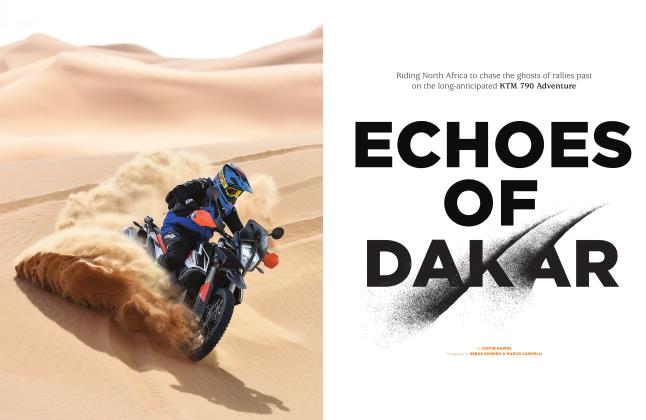

FeatureEchoes of Dakar

Issue 2 2019 By Justin Dawes -

Reviews

ReviewsBalance of Power

Issue 2 2019 By Michael Gilbert -

Elements

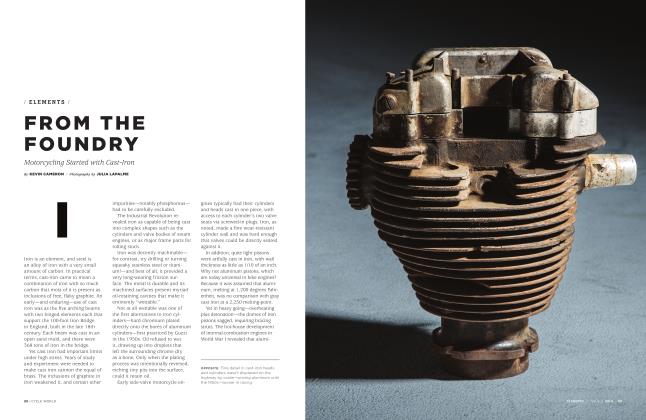

ElementsFrom the Foundry

Issue 2 2019 By Kevin Cameron -

Reviews

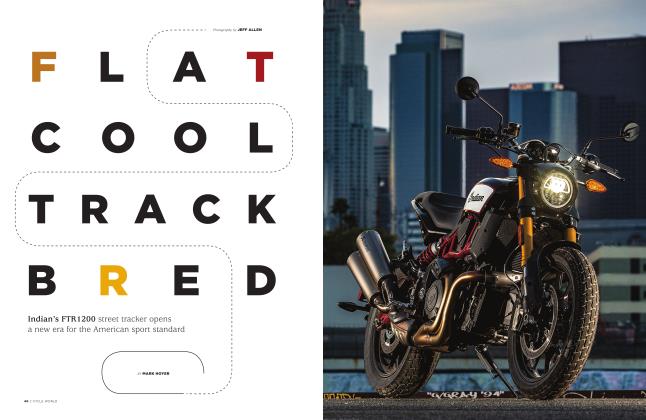

ReviewsFlat Cool Track Bred

Issue 2 2019 By Mark Hoyer -

Origins

OriginsThe First Superbike

Issue 2 2019 By Kevin Cameron