Porcupine

Sometimes fast, always flawed, the AJS Porcupine’s prickly history began with a supercharger and a host of innovations

January 2 2018 Kevin CameronSometimes fast, always flawed, the AJS Porcupine’s prickly history began with a supercharger and a host of innovations

January 2 2018 Kevin CameronPORCUPINE

Sometimes fast, always flawed, the AJS Porcupine’s prickly history began with a supercharger and a host of innovations

KEVIN CAMERON

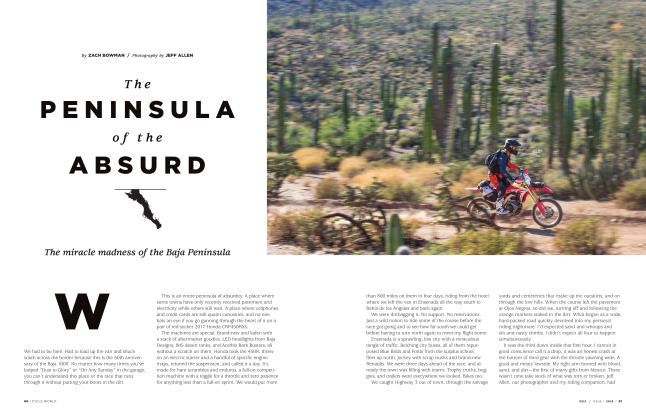

Here in all its dark, fluid grace is the AJS Porcupine, a parallel-twin that was England’s postwar bid to rise above the limited power of traditional British racing singles with more cylinders and higher revs. In 1949— the first year of the new FIM world championships— rider Les Graham would give the Porcupine its only championship. The bike in these photos was not the championship-winning 1949 E90, but rather the last redesign in 1954 with 45-degree-inclined cylinders.

The name—Porcupine—originated with the quill-like spike finning between the pair of cam covers of the original engine, whose cylinders were just 15 degrees above horizontal.

In the 1920s AJS had led the high-tech development of overhead-valve and then overhead-cam racing singles in the Isle of Man TT races. The Collier brothers, who joined AJS, Matchless, and Sunbeam into Associated Motor Cycles (AMC), had themselves been pre-World War I TT winners.

The Porcupine’s usual origin story is that it was sketched on napkins during tea breaks as World War II raged on. In fact, its creation was more deliberate. In 1939, AMC’s Donald Heather had teamed former Norton race boss Joe Craig with draftsmen/detail designers Vic Webb and former Vincent engineer Phil Irving in an off-limits drawing office. The main task of that office, Irving says in his autobiography, was “mainly the design of a racer-type named E90S, the ‘S’ standing for ‘Supercharged.’”

The goal of the E90S was to overcome the multicylinder head start of BMW (which won the 1939 500cc TT with a supercharged flat-twin) and Gilera (which had won the 1939 European championship with a supercharged four).

Why a twin? AJS had shown an air-cooled V-4 street bike at the 1935 Olympia Show, then invested much effort in trying to race it in various forms. What did the V-4 teach them? That adding complexity increases a bike’s weight faster than it improves its performance. Rider Walter Rusk on the supercharged and liquid-cooled AJS V-4 was as fast as the Gilera at the 1939 Ulster Grand Prix, but the bike remained a monster to handle. Harry Collier’s response was to begin designing a supercharged in-line triple. The engine was mounted "headfirst” to deal with the extra heat of supercharging—its cylinders horizontal so air would directly hit the cooling fins between its cam boxes.

When Joe Craig was hired that same year, Collier irritably ordered this Triple’s parts and drawings destroyed, saying, “Joe Craig will never learn anything from us here.”

Craig and AMC planned a compact unit-construction liquid-cooled parallel twin with a Zoller eccentric-vane blower mounted atop its gearbox. There is evidence that this engine may have had vertical cylinders with intake ports between the valves (to prevent charge loss from intake to exhaust), fed by long intake pipes from the blower. With nothing radical in its design, this engine was expected to make 65 hp—10 more than the complex and heavy 1939 V-4. Frame and cycle parts were drawn by Phil Walker, who would later design the 350cc AJS 7R “Boy Racer” OHC single.

Craig saw an engine run on the dyno before he returned to Norton in 1946. Though England had been on the winning side in World War II, times were hard: Wartime food and fuel rationing remained in force. There was nothing extra. Now came a terrible blow: In September 1946, racing’s ruling body banned supercharging. The new AJS racer was unusable.

With Craig at Norton and Matt Wright and Phil Irving departed to Vincent, the task of saving the company’s investment by conversion to air-cooling and unsupercharged operation fell to Vic Webb. Irving noted that the result “was equipped with a new cylinder head designed by Vic Webb with conventional inlet ports, and with transverse fins broken up into a number of pieces (the ‘porcupine quills’) to assist airflow.”

The near-horizontal cylinder position of this E90 clearly came straight from Harry Collier’s Triple. Power was disappointing—29 hp on its first dyno run, rising to 36.8 by its press launch in May 1947—about the same as the 500cc single-cylinder Manx Norton on the rationed low-octane fuel.

The engine was ruggedly built for supercharging with both crankshaft and gearbox unitized in the same Elektron magnesium casting. Forged RR56 aluminum con rods used Vandervell plain insert bearings. A four-speed vertically stacked Burman crossover gearbox was driven through a gear primary and large dry clutch. A Y-shaped housing on the right contained nine gears driving the two overhead cams plus an accessory shaft across the top of the gearcase. This drove the magneto and oil pumps for this dry-sump system.

Design for supercharging had left its mark. Combustion chambers were deep, with large-stemmed aircraft-type valves set at a 90-degree angle—not the faster-burning and shallow 58 degrees that Norton would a year later give its export twins. Exhaust ports were huge. The mounting pad for the Zoller blower remained atop the gearbox. Crank mass, originally supplemented by the substantial supercharger rotor, was low, leading to stalling in slow corners.

Intake flow entered two Amal GP carburetors, which were supplied with fuel by a single cylindrical float bowl between them. With carbs at roughly 45 degrees, curved intake pipes were required to carry mixture to the ports. One of the Porcupine’s several riders, Ted Frend, would years later say that carburetion had been the bike’s greatest problem.

In the 1947 Isle of Man TT, Les Graham was pushed down to sixth by a crash, then had his chain run off.

After a year’s additional development, none of the Porcupines finished in the 1948 TT. Unlike Norton or Velocette, AJS had no continuing in-house racing know-how. AMC boss Donald Heather therefore asked Matt Wright (lately returned from Vincent) to take over development. He further adapted the Porcupine to unsupercharged operation, first reducing valve angle to 79 degrees, and then adding a deflector in each port to encourage turbulence and improve combustion.

Wright’s program achieved 50 hp, but company policies worked against them. Riders were required to use AMC’s own unadmired rear suspension units. The use of streamlining was forbidden, and when engine airflow pioneer Harry Weslake offered his services, Donald Heather remarkably turned him down.

Everything seemed to be going their way in the 1949 TT, with Les Graham and Ted Frend leading 1-2. Then Frend crashed out, leaving Graham leading by miles, just 2 miles from the finish. Then the engine stopped. With Jock West (TT and grass-track racer who also worked for AMC in sales) trotting beside him shouting encouragement, Graham pushed in the 2 miles for 10th place. The magneto drive had failed.

Graham took several victories (and a retirement with a split fuel tank) to take the world 500cc title by one point.

Other teams advanced more rapidly. Norton’s new Rex McCandless-designed “Featherbed” twin-loop chassis made the Manx faster. Geoff Duke would easily have been champion on a 500 Manx in 1950 had his tires not delaminated (cotton plies at 150 mphl). Gilera and newcomer MV Agusta saw that handling makes power usable. Both “Nortonized” their air-cooled in-line four frames as fast as they could—abandoning spindly prewar chassis, jerky friction dampers, and antiquated girder forks.

In the 1950 TT, the Porcupine’s best finish was Graham’s fourth—behind three Featherbed-framed factory Norton singles.

The Porcupine’s 21-inch wheels were now downsized to 19. Engine oil was moved to a boatlike underengine sump— to ease starting by allowing preheated oil to be poured directly into the engine. Wheelbase and weight were reduced.

Despite such effort, AJS steadily lost ground to the Gileras. While Norton’s Craig gained wisdom from punishing dyno-race simulations, political forces within AJS looked for someone to blame for their lack of success.

For 1952, the machine was completely redesigned by Ike Hatch and Phil Walker, lifting the engine’s cylinders to 45 degrees. Its cooling spikes were replaced by normal hns. A “softer” chain drive was substituted for the gears that had previously driven the magneto. Wright commented that “this whole project was a total waste of effort.”

For 1954, AJS hired the man then considered to be England’s top racing-development engineer: Jack Williams. He replaced the AMC rear suspension units with the Girlings preferred by everyone else. Rubber sleeves prevented the previous “shaking off” of the carburetors. A new fuel tank, pump, and weir system (a kind of header tank and dam/ spillway setup for consistent fuel delivery) replaced troublesome and vibration-sensitive float chambers.

In the 1954 TT, AJS team rider Derek Farrant crashed on Lap 1. Rod Coleman ran fifth for three laps but pitted with a split fuel tank, coming home 12th. Bob McIntyre finished 14th.

As postwar auto production took sales from motorcycles, GP racing was revealed as an extravagance—not the powerful sales builder it had been in the 1920s. Triumph and BSA, who had hit the US bike market early, prospered. Those counting on domestic sales did not. At the end of 1954, all British factory GP teams ceased operation.

Had the Porcupine succeeded, it would today be remembered for its innovations—unitized engine/transmission construction, gear primary, and a modern chassis with hydraulic-damped telescopic fork and swingarm.

There were two reasons for the Porcupine’s lack of success. First, the hasty conversion from supercharged to unsupercharged operation was incomplete and failed to incorporate best contemporary practice, and second, AJS management had made the classic mistake of initiating a project that needed more-intensive development than they were willing or able to provide.

The Porcupine remains a glorious relic of an era marked by experimentation and possibility and survives to remind us of our successes and failures.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue