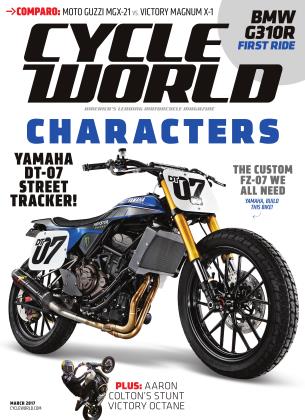

American Flat-Track Revival

Is the racing sport of turning left finally making the right turn?

March 1 2017 Andrea WilsonIs the racing sport of turning left finally making the right turn?

March 1 2017 Andrea WilsonRace Watch

DIRT, REBRANDED TWINS VS. TWINS SINGLES VS. SINGLES INDIAN CIRCLING

THE VIEW FH am msmE THE PHaHOEH

AMERICAN FLAT-TRACK REVIVAL

FLAT-TRACK

Is the racing sport of turning left finally making the right turn?

Andrea Wilson

Flat-track racing has pretty much been awesome since, well, two motorcycles met some neatly arranged left turns on dirt. Over the decades, the success of the Grand National Championship has gone up and down, but there has never been any question that the sport has offered some of the best motor racing of any kind on the planet.

Even with its great action and strong tradition, flat-track’s popularity on the national level dwindled in the modern era. The only thing that kept it going was a tightly knit core of enthusiasts who put money into the sport purely out of love. And there has been but one factory committed long-term: Harley-Davidson. Without this love for the sport and this one factory, it’s unlikely that flat-track would have survived as a professional national series.

But in recent years, flat-track has been rediscovered by a wider audience. The bikes have always been pure, but it’s the accessibility, both from a participatory standpoint and as a fan on the national level, that makes flat-track so attractive. You can walk pit areas and talk to the top riders, who are glad to share their time with you. Custom builders have widely adopted the tracker style and Hooligan racing—a run-whatya-brung-grassroots-racing emergence typified by Dirt Quake (Race Watch, Oct. 2015) and similar events—has brought even more interest.

There’s also been a high-profile push on the world stage with guys like Valentino Rossi, Marc Marquez, and Troy Bayliss sharing their passion for the sport. And America’s own Brad Baker has banged bars with Marquez at the annual Superprestigio indoor short-track race in Barcelona, Spain. To add to that buzz, flat-

track landed a spot in X Games, further widening the audience. Basically, flat-track is burning bright again and, as a result, has a window of opportunity. That’s whyAMA Pro Racing’s flat-track boss Michael Lock has introduced some big changes for the AMA Pro Flat-Track series in 2017, starting with a complete rebranding to American Flat-Track, new logo and all.

“The last thing we wanted to do was mask it all with this feeling that nothing’s changed,” Lock says. “It was imperative that we apply a fresh look onto the top of the sport in order for people to know we were doing something new. We have this long, rich history. It’s the oldest form of motorcycle racing. We wanted to communicate [our new path] while acknowledging the heritage.”

But recapturing the sport’s former glory requires more than a new name and logo. So a plan was formulated and changes were made in three key areas: class structure, rules, and race format.

The first, and perhaps most important area, was class structure. Starting in 2017, the premier class—AFT Twins—will only be racing twins, and the support class—AFT Singles—will stick with 45OCC singles. “The racing classes were just fine

for the existing competitors, the existing teams, and maybe even the existing fan base,” Lock begins. “But the more I looked outside of that world I found that we were struggling to make a meaningful connection with a whole load of potential stakeholder groups around the sport that would help us grow it.”

To illustrate the problem with the old class structure you need not go far. The 2015 season finale was held on an indoor short track in Las Vegas, a home race for one of Jared Mees’ principle team sponsors—Las Vegas Harley-Davidson. Mees was able to clinch his third Grand National Championship at his sponsor’s home race but while riding a Honda. “There is no other form of pro sport I can imagine, no other form of professional auto or motorsport in the world where that could happen,” Lock says. “I understand why it happened, but I vowed that would never happen again.” This sort of convoluted scenario is not only unappealing to the manufacturers, but it’s also confusing for fans trying to follow the sport. “If we are to grow a new generation of fans, particularly young fans, we have to dial down the complexity and the barriers to understand flat-track, and we have to dial up the accessibility,” he says.

“In almost every other form of motorcycle sport and car sport, there is this triangle of success:

It is an athlete, a machine, and a team. Those are the three things you need. You need them all to be the same every week, otherwise there’s no story to tell.”

Fans are critical to a sport’s success, but without money there would be no narrative in the first place. Creating a manufacturerfriendly environment was a critical first step to take the series forward. “In speaking to every OEM in the industry I found this enormous gap between their participation and their goodwill,” Lock says. “So a primary driver of separating the classes into racing twins all year or singles is to get

the attention of that dozen motorcycle manufacturers out there, and say, ‘Hey, we’ve cleaned up the format, now can I ask for you to help?’ So if we achieve nothing else with the class change, we’ve achieved a lot with that.”

Another part of cleaning house and attempting to sell to motorcycle manufacturers was simplifying the rules, most notably, tightening up the displacement range for the Twins class from 55OCC to i,200cc to 65OCC to 990CC. “It’s still too broad in the long term, but what we don’t want to do is just exclude bikes that are currently on the grid,” Lock explains. “So we’re trying to send out a message to say, long-term, the 650 might go to 750, and the 990 might come down to 850, for example.”

Lock also envisions a productionbased championship. At the moment, purpose-built race machines line up alongside production-based machines. Harley-Davidson XR75OS, the dominant flat-track bike of the past 40 years, have now been joined by the brand-new Indian Scout FTR750, reigniting one of the oldest motorcycle racing rivalries. The rest of the field lines up on bikes that started out as street machines.

With renewed interest comes increased scrutiny. And there have been grumblings about Indian coming in with a race-only engine that wasn’t for sale when the FTR750 made its race debut at the Santa Rosa Mile (“Indian Throws Down the Glove,” Dec. 2016).

“Indian wanted to get into the sport and be competitive as quickly as they could because they saw an opportunity and growth in pro flat-track,”

Lock explains. “The only way they could execute that in a short space in time was to create a bike for flat-track, much in the way Harley-Davidson did 40 years ago with the XR. But by the end of 2019 we will be looking to have only production-based engines eligible for competition. Indian understands that they’ve got a window to develop and compete with this bike, and that’s the same for anybody else.”

It’s unlikely anybody else is working on a prototype flat-trackspecific powerplant, but Lock says if a manufacturer has the inclination, any prototype fitting the rules would be allowed.

Aside from a race-format change (a tournament-style elimination program will keep the top racers on track and in front of spectators more through race day), the new flat-track presents itself much like the old flattrack but in a package the series hopes will bring more fans and sponsors to the races, to TV screens (every round on NBC Sports Network), and streaming feeds (fanschoice.tv).

American flat-track has seen many attempted “revivals” over the years, but none has been supported by the broader cultural popularity we are witnessing. If there was ever a time for big growth and success for flattrack, that time is now. E1MM

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Service

MARCH 2017 By Ray Nierlich -

Characters

CharactersDt-07 Street Tracker

MARCH 2017 By Bradley Adams -

Ignition

IgnitionSimple And Straight-Forward

MARCH 2017 By Kevin Cameron -

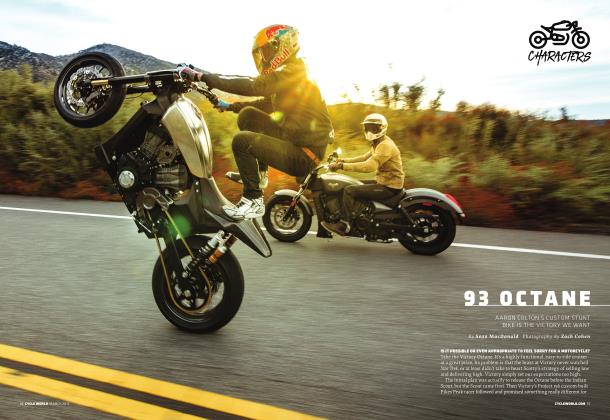

Characters

Characters93 Octane

MARCH 2017 By Sean Macdonald -

Up Front

Up FrontDeath of the Neo-Custom

MARCH 2017 By Mark Hoyer -

Ignition

IgnitionHurricanes, Poop, And Flat-Tracks

MARCH 2017 By Peter Jones