Simple And Straight-Forward

WHEN WAS THE GOLDEN AGE OF MOTORCYCLING? IT WAS WHEN YOU WERE 20.

March 1 2017 Kevin CameronWHEN WAS THE GOLDEN AGE OF MOTORCYCLING? IT WAS WHEN YOU WERE 20.

March 1 2017 Kevin CameronSIMPLE AND STRAIGHT-FORWARD

IGNITION

TDC

WHEN WAS THE GOLDEN AGE OF MOTORCYCLING? IT WAS WHEN YOU WERE 20.

KEVIN CAMERON

Okay, it’s 1966 and we’re about to set ignition timing on a Yamaha TD1-B 250 roadracer. These are the good old days, right? No confusing suspension adjustments, no 10 levels of traction-control intervention—just the most basic stuff. To set timing, we need a dial gauge to tell us when the piston is 2mm before top center, and to mount that gauge, we screw a cadmium-plated (Eek! Cadmium is a heavy metal, man! What’re you doing—tryin’ ta poison yerself?) dial gauge adapter into the spark plug hole. To reach down to the piston crown we have various dial gauge extensions... Ah, here’s the one. I slide the dial gauge with its extension down into the adapter (having previously put the piston at approximate TDC by poking a screwdriver down the plug hole) until I feel it touch and turn the knurled setscrew to hold it in place. Now with this 12mm box wrench on the magneto rotor bolt, I back the crank up to be sure I have enough dial gauge travel to measure 2mm. If not, I set it a bit deeper. Then, rocking the crank back and forth, I locate TDC and by turning the bezel ring of the dial gauge, I rotate its zero to line up with the gauge needle.

The idea of this is to adjust the contactbreaker points of the magneto so they open at exactly 2mm BTDC. How will I know? Two possibilities: the “smoker’s way” and the clean, smokeless, modern high-tech way. A smoker pulls some of the really thin cellophane off an open pack of ciggies and, slightly opening the number two cylinder’s contacts with the fingers of one hand, slips the end of the bit of cellophane between the points with the other. Pulling gently on the cello, I rotate the crank toward that 2mm BTDC point, but I’m watching carefully to see where the needle is when the cello slips out of the points as the little magneto cam on the end of the crank opens them. If this

happens early or late, the next job is to rotate the base on which the number two set of points is mounted in the right direction then tighten its clamp screws to hold it there.

Mind you, the process of disturbing the points may have changed their gap when open. That gap may have to be reset as well. Back and forth we go with these adjustments (like a novice driver, trying to park a car) until we have the cellophane slipping out just at 2mm BTDC and the correct gap. Small adjustments are made by tapping on the stationary point’s bracket.

Now to do the number one cylinder. Kind of like doing your income tax twice, just for fun.

The non-smoking method? Clip a palegreen Okuda Koki resistance meter across the points and watch for the swing of its needle, indicating points opening.

Later, starting the engine, we reflect that each time the floppy, pressed-together crankshaft feels the sudden slap of combustion, it assumes a subtly different shape, easily able to convert 2mm into 2.3 for one cylinder (over-advanced, inviting the detonation gremlin to dine on that piston’s tender edges) and 1.4mm for the other (retarded, with some loss of power).

A friend, seeing me at this task, proposed, “If starting the engine this time knocked it out of time, maybe starting it a second time will knock it right back where it should be.”

In my mind I know he’s right—at 10,000 rpm this thing’s surely going in and out of time thousands of times per lap. If I’d known then what I know now, I’d have shrugged like Jean-Paul Belmondo; the recommended spark plugs for this model— NGK B10EN—would today be regarded as super cold, as in, “No wonder it fouls plugs—those are practically Top Fuel sparklers.” In other words, cold-running plugs were just a crude form of insurance (we

BY THE NUMBERS

35 CLAIMED HORSEPOWER OF THAT TD1-B (PROBABLY OPTIMISTIC)

54 POWER OF YAMAHA'S 1964 SPA-WINNING RD56

100 POWER OF TOP 250 TWINS WHEN THE CLASS ENDED IN 2009

also carried fouling-resistant 7s for cold starting and 11s in case it got wicked hot).

Carburetor jetting is another aspect of the simplicity and straightforwardness of these bikes. In retrospect, jetting seems like something Druids practiced at Stonehenge. There is an idle air screw (1-1/2 turns out), but controlling mixture as you initially lift the throttles is the slide cutaway (4.0—the bigger the number, the leaner the slide), followed by the needle setting (needle is 6A1, clip in center groove), and finally, the main jet (nominally 190, but...). In case all that sounds even slightly precise, the foam-mounted float bowls (responsible for maintaining a constant fuel height for accurate flow control) did not surround each carburetor as a part of it (concentric!) but were “remote”—inches behind the carburetors. That way, fuel sloshes away from the carbs during accel-

eration (lean—gremlins approach) and toward them during braking (a process which safety-concerned moderns should know released asbestos fibers). But it all made sense years later when I learned the Yamaha race team in 1963 were finally able to get their RD56 machine to accept full throttle on the Belgian GP course at Spa by improvising one float bowl ahead of and another behind each of its two carburetors. This enabled Fumio Ito and Yoshikazu Sunako to finish first and second, relegating the great Tarquinio Provini and his potent factory Morini to third. A year later a new butt would be on its seat—that of a very young Giacomo Agostini. Mikuni read the race report and came out with prototype concentric float bowl carbs the next year—the familiar VMs used so extensively in the 1970s. Through difficulties, we ascend to the stars.

Just as radiation workers wear

film badges to accurately measure their cumulative exposure to the ionizing rays, our TDis had a cumulative vibration dosimeter system, consisting of engine mounts, which broke in a known sequence. Ten years later the same was still true of the 120-hp TZ750— if your frame failed to crack in the standard places, in the usual time, it suggested you weren’t pushing it.

So here’s the deal. Got to admit—looking back at the TDi is comical. Stuff broke all the time so you were never without tools in your hands. It was not a golden age and was neither simple nor straightforward, so let’s forget any retrospective notions of an easier time. Today’s super-sophisticated bikes seem fantastic now, but think about that. In 50 years, young people born in 2045 will giggle at their crudity while you, bent over with age, defend 2016 as a golden age of simplicity and straightforwardness. CTO

STUFF BROKE ALL THE TIME, SO YOU WERE NEVER WITHOUT TOOLS IN YOUR HANDS.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Service

MARCH 2017 By Ray Nierlich -

Race Watch

Race WatchAmerican Flat-Track Revival

MARCH 2017 By Andrea Wilson -

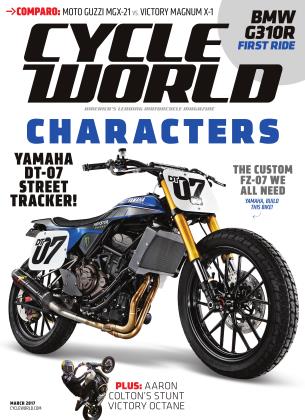

Characters

CharactersDt-07 Street Tracker

MARCH 2017 By Bradley Adams -

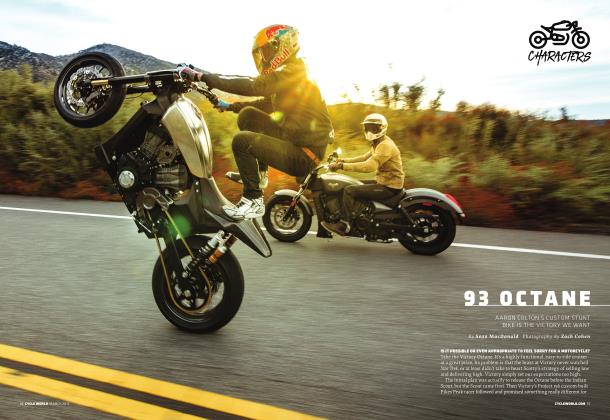

Characters

Characters93 Octane

MARCH 2017 By Sean Macdonald -

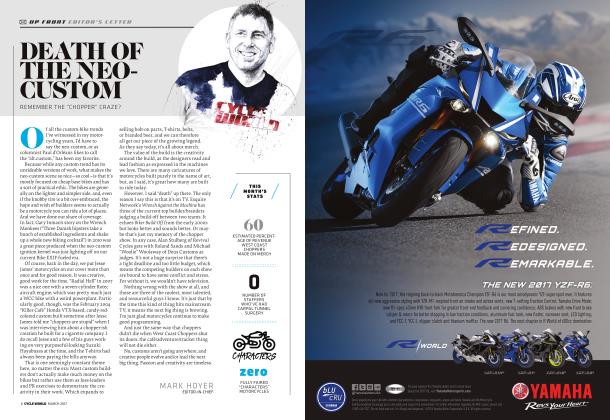

Up Front

Up FrontDeath of the Neo-Custom

MARCH 2017 By Mark Hoyer -

Ignition

IgnitionHurricanes, Poop, And Flat-Tracks

MARCH 2017 By Peter Jones