Indian Throws Down the Glove

WILL INDIAN'S NEW FLAT-TRACKER CHANGE THE FACE OF AMERICAN DIRT-TRACK RACING?

December 1 2016 Kevin CameronWILL INDIAN'S NEW FLAT-TRACKER CHANGE THE FACE OF AMERICAN DIRT-TRACK RACING?

December 1 2016 Kevin CameronINDIAN THROWS DOWN THE GLOVE

CW EXCLUSIVE

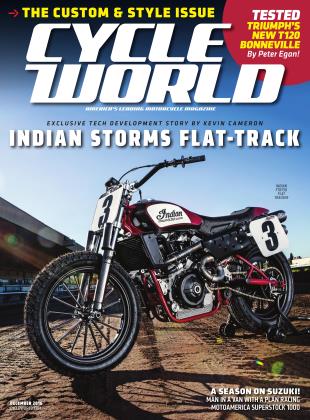

INDIAN FTR750 FLAT-TRACKER

WILL INDIAN'S NEW FLAT-TRACKER CHANGE THE FACE OF AMERICAN DIRT-TRACK RACING?

Kevin Cameron

Indian is challenging the weight of history by building a race-only 750 dirt-tracker for AMA Pro Grand National events. Since Bill Tuman won Indian’s last Grand National Championship by topping the Springfield Mile on a Scout in 1953, Harley-Davidson-mounted riders have won the GNC 50 times. How do you like those odds? Indian’s challenge is its 109hp V-twin FTR750 flat-track racebike, based on no production model. There is nothing more American in motorcycling than its century-old fairgrounds flattrack racing. Indian’s challenge asks, “Who is the most authentically American manufacturer?”

When I search for a similar long shot,

I think of Honda who, with the help of Gene Romero and others, turned its unlikely CX500 engine sideways and transformed it into the RS750, which won five AMA GNCs.

Indian management heavies made their remarkable decision late in 2015.

I went to see the chassis with rapid-prototyped (plastic) engine and bodywork in the second week of May and spoke by phone with engineer Urs Wenger of Polaris/Swissauto. In early June, I flew to Switzerland to see the 106-pound engine, both apart and running on the dynamometer, and in July I attended a closed Indian test of the complete machine in the hands of Jared Mees, at the Charlotte, North Carolina, Half-Mile. That is fast development of a kind that takes full commitment and serious R&D capability.

Why would Indian executives back this? Maybe for the same reason that Honda entered European motorcycle GP racing in 1959: to establish its name worldwide in capital letters.

Who will answer this challenge? Harley-Davidson must, for to do otherwise after so many years of success would risk more than competing does. The other successful engine in the series is the Kawasaki Ninja 650 twin, originally developed to first 698CC and then 749CC displacement by former Harley-Davidson flat-track crew

chief Bill Werner, the mechanic and team leader behind 13 XR-750 Grand National Championships. The Kawasaki is now kept in the limelight by Bryan Smith on the Howerton Crosley bike, who won the 2016 championship in a fight to the end with Jared Mees. Does Kawasaki help teams racing its engine in AMA Pro? Who knows, but a position has been attributed to Kawasaki in paddock conversation. It says “No, we cannot race a 750 in a series that permits 1,000s to compete, especially since 750s are limited to a 38mm throttle body while 1,000s get 55mm.”

It’s worth knowing why the 1,000s haven’t worked so far (they were added to the class in hope of making low-buck teams competitive). The basic answer is, big ports, big cams, and big power. That means the i,ooocc builders are fighting

the very same problems Kenny Roberts faced on the 1975 Indianapolis Mile, riding the two-stroke Yamaha TZ750—too much power, hitting much too hard. Riders today, faced with uncontrollable power, try to tame it by modulating the back brake until the disc glows red and the pads wear down to the steel, sparking furiously.

How do you enter a racing series in which you have zero experience? You begin by studying existing best practice: Harley-Davidson’s aluminum XR-750 that has been evolving since 1972. You measure winning chassis, locate major components, analyze swingarm squat/ antisquat geometry. You dyno the best engine you can lay hands on, to understand the amount of power required and the shape of its torque curve.

This showed that winning bikes have 95 to too rear-wheel horsepower, with peak torque that begins around 7,000 and hangs on forever. Winning torque curves have no dips or peaks, just nice smooth delivery that a rider can count on as he or she feels for grip on what dirt-trackers call “that 70-hp tire.” That set the goal at 110 crankshaft horsepower at 10,000 rpm. Another thing: If you’re geared to come off the corners strongly, your engine hits peak horsepower rpm well before the next corner. To get there, it has to over-rev the peak without either falling on its face or hurting itself mechanically.

Numbers for the new Indian Scout's steel-tube chassis are classic: Wheelbase is 55 inches with a nominal steering-head angle of 25 degrees (with 2 degrees of adjustment). Trail is 3.9 inches but can be altered by changing the offset between the fork legs (an Öhlins unit of the type being used in flat-track) and steering axis. Standard offset is 53mm. The frame has an adjustable swingarm pivot height (this controls the squat/antisquat behavior of the rear suspension as the rider feeds throttle to accelerate off the turn). The goal is to keep machine attitude where the rider likes it, neither squatting down (causing front push) nor topping

(which stops suspension movement). Under a tank-shaped cover are a 2.2-gallon fuel tank up front and an intake air filter case behind (with its intake through louvers in the top and visible to the rider).

Everything has been made adjustable to allow best engine position, overall ride height, and rider fore-and-aft position to be found. Steel tubes look spindly to sportbike riders, but dirt tracks aren’t

smooth, and suspension can never do the whole job, giving value to chassis flex.

First engine run was scheduled for May, and such a fast pace dictated what Wenger called “low-risk design.” That meant eliminating experimental materials or concepts whose failure might cause delays. No exotic materials are used.

The 106-pound engine was designed as a 53-degree V-twin with the goal of making it narrow and compact enough to allow wide option of placement in the chassis. The narrower the V angle, the more a V-twin shakes like a single. The less buzzing there is, the better the rider can feel what the tires are saying, so vibration had to go. When an engine has 50 percent of its reciprocating mass balanced by weights on the crankshaft, the original up-and-down shaking force of its pistons becomes a largely constant imbalance vector, rotating opposite to the crank. This can be canceled by creating an equal and opposite imbalance, also rotating opposite to the crank. This was provided by incorporating eccentric weights into the two cam drive reduction gears—one on the right for the front cylinder and vice versa. A smooth engine also stops the long and lamentable tradition of vibration-cracking of parts.

Unlike the XR-750, whose rolling bear-

ings now give it very short crank life, the new Indian has all plain bearings with side-by-side split-and-bolted connecting rods on a single crankpin (front cylinder links to the left con-rod). As in Ft practice, oil enters the end of the one-piece crank. Target engine runtime between services is 30 hours.

The time-honored Harley-Davidson XR-750 is a two-valve design, but today four lighter, smaller valves driven by

overhead cams are the choice for delivering flat torque and surviving over-rev. Why? It’s easier to accurately control the motions of smaller, lighter, paired valves than it is a larger single one with a pushrod and rocker.

Wenger said upper-end design was a matter of sizing the valves for the airflow of an engine making no hp at 10,000 rpm. That set the bore at 88mm, and to give 75OCC displacement that implied a 61.5mm stroke. Valve included angle (the angle at which intake and exhaust valve stems tip away from each other) is determined by the size of the modified production Scout cam chain sprockets. The 33.5mm intakes tip away from bore centerline at 10.5 degrees and the 30mm exhausts at 12.5, for a 23-degree included angle. The resulting shallow chamber is fully machined to control piston-to-head clearance at TDC and provide the planned 14.0:1 compression ratio. Each valve has its own inverted-bucket-type tappet from the production Scout with valve clearance

set by selective fit, eliminating valve shim spitting.

Each head has an intake and an exhaust cam, driven by silent chain that is fully controlled by contact with arcshaped plastic-faced chain guides.

Harley-Davidson's XR-750 is air-cooled, but air-cooling forces engine temperature to rise and fall with the thermometer, possibly being pushed into heat-driven detonation on hot days. Liquid-cooling was the choice for the FTR because it enables use of very high compression ratio without inviting either piston cracking or detonation.

When I asked Wenger whether Computed Fluid Dynamics was used in design of this cylinder head, he said that while CFD is valuable for emissionsregulated engines, race-only designs don’t require it.

A 60/32 gear primary drives the usual multi-plate clutch and a right-hand shift four-speed gearbox (adequate for dirttrack). In AMA Pro flat-track, part of

STEEL TUBES LOOK SPINDLY TOSPORTBIKE RIDERS, BUT DIRT TRACKS AREN’T SMOOTH, AND SUSPENSION CAN NEVER DO THE WHOLE JOB, GIVING VALUE TO CHASSIS FLEX.

race drama is the starting of engines with Indy-car-like external starters. But Wenger’s FTR engine, weighing only 70 percent as much as the XR, could easily have carried a starter. He said with amusement, “If we have an integrated starter, everyone will be pissed off!”

A much-admired feature of the XRis its big steel crank wheels, whose rotational inertia smooths power delivery. One rider observed that crank inertia does help hook-up on slippery or loose surfaces but may sacrifice acceleration on higher-grip tracks. Therefore the FTR has been provided with three weights of easily changeable external flywheel.

Dyno running impresses because the test engine seemingly hammers and bellows, but a look at the control console tells you all is normal—everything’s in the green. Through testing, cam profiles and intake length have required no change. Wenger says, “If the client is willing, I like to run a 24-hour fullthrottle test to chase out any gremlins.” At the Charlotte test I observed in July, it was 97 degrees. A tech poked the external starter into the left side

of the FTR engine and it barked to life instantly—every time. Throttle response was immediate. This is a fuel-injected engine, using stock Scout injectors.

On the track, a banked half-mile bowl of red clay, the exhaust note booms and changes register as the engine accelerates. When the rider is satisfied that all is well, he runs blocks of laps. At each stop, six technicians move through a test protocol. In racing, test sequencing resembles a computer program, with interrupts and “if...then” decision points.

I’m watching the rear tire as the bike enters turn three. With 20 psi in the tire, there is little rear wheel pattering despite the washboard from last night’s National. I follow the wall deeper into three, and can see that the rear tire leaves a trace that tells the suspension’s story. On a smoother

line, the width of the trace varies but contact is continuous. Up higher, the tire leaves a dotted line. During heats and racing, riders constantly seek the fastest surface as it moves up or down and changes character.

Grand National twins rider and Cycle World contributor Cory Texter was given two exits on the bike. He has, he told me, ridden most types of bike in the class, so he has real basis for comparison.

After his first run he said, “Power feels between a Harley and a Kawi. These are the best brakes I’ve ever used! I really liked the chassis.”

After his second go: “I’m just spinning, just slightly, off the corners. Man, it handles really good.”

Indian first raced the FTR750 at the Santa Rosa Mile, the final round of the 2016 GNC season. The goal all along, according to Indian Product Director Gary Gray, was to have a bike that tells its rider what’s happening next (Feel), a bike that hooks up and stays that way (Traction), and a bike that doesn’t break (Reliability). The team explored its possibilities with the adjustable nature of the bike. What you see in racing flat-track when two riders push each other to the limit is each one’s constant search for some slight advantage, for ways to extract just a bit more from a bit better match of bike to dirt. Timed laps in closed tests have value, but the ultimate value of what Indian has created emerged at Santa Rosa in actual racing. Past Grand National Champion Joe Kopp, now 47, qualified by finishing second in his heat (wheelying off of turn two on the opening lap!), won the Dash for Cash, and finished seventh in the main after getting the holeshot and leading the first lap. Kopp was also one of only four riders in the main to turn a sub40-second lap.

The result of this strong showing was teams lining up to buy the new bike, which will be for sale next year at an as-yet-to-bedetermined price.

On that day in Santa Rosa, Indian showed its commitment to American flat-track racing changed for good, in all the senses that can imply.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Race Watch

Race WatchMan. Van. Plan.

DECEMBER 2016 By Mark Hoyer -

Service

ServiceService

DECEMBER 2016 By Ray Nierlich -

Ignition

IgnitionRubber Revolution

DECEMBER 2016 By Kevin Cameron -

Indian Ftr750 Is On Track

DECEMBER 2016 By Cory Texter -

Up Front

Up FrontAmerican Flat-Track

DECEMBER 2016 By Mark Hoyer -

Ignition

IgnitionVirtual Combustion

DECEMBER 2016 By Peter Jones