TWINS NOT TWINS

TWO UNIQUE SOLUTIONS TO THE TWO-CYLINDER SUPERBIKE POWER PUZZLE

Kevin Cameron

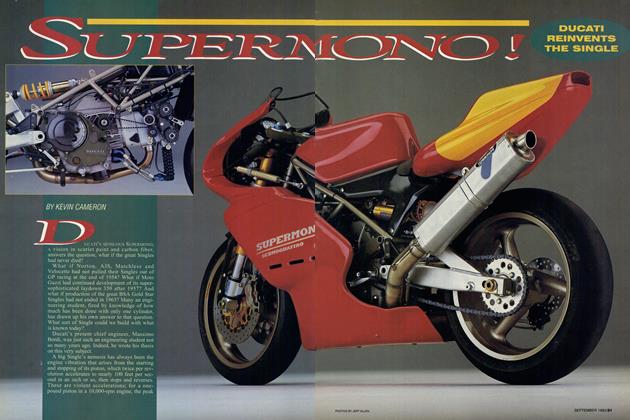

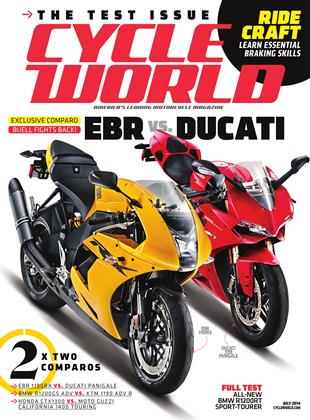

DUCATI AND EBR have taken different paths toward the same end: an ultra-highperformance V-twin superbike. Ducati's Panigale has no frame; a rigid box, doubling as the intake air plenum, is bolted in Vincent fashion to the cylinder heads, just as Ducati did in MotoGP, with the steeringhead made as a forward extension of it.

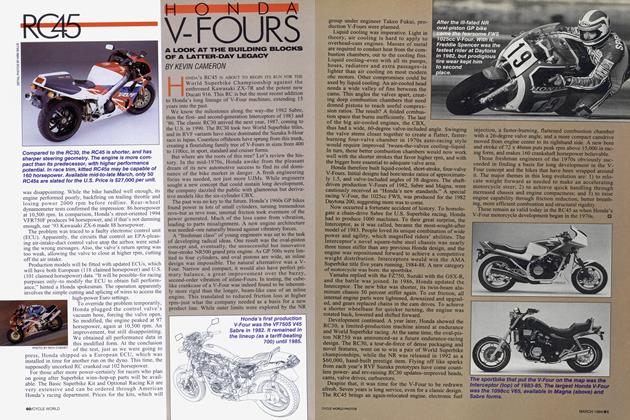

EBR combined functions on the 1190RX just as effectively, but differently. By putting the fuel into the beams of a more conventional cast aluminum perimeter frame, EBR eliminated the usual volume competition between fuel tank and intake airbox.

Ducati has stayed with Fabio Taglioni’s original 90-degree cylinder V-angle because it uniquely can be made selfbalancing. The cost of this reduced vibration is increased

bulk; the length of the horizontal cylinder pushes the heavy crankcase/gearbox unit rearward, making it harderto get enough load on the front tire to keep it steering out of corners.

EBR chose a narrower72degree cylinder angle to reduce bulk but did not close it up to the 60-degree setup Aprilia chose for its previous superbike twins because that left too little room in the Vee forthe desired intake system. The cost of this desirable compactness is a need for balance shafts to quell the shaking that appears as V-angle is reduced from 90 degrees. Why not just man up and let 'er shake like British twins did? Light, stiff aluminum chassis are vibration-sensitive. Then why not rubber-mount the engine? Because a rigidmounted engine contributes valuable stiffness to the chassis, saving significant weight.

In the design of the engine itself, Ducati followed Claudio Domenicali’s initiative to provide power at least equal to that of four-cylinder rivals.

To get it, extreme bore-andstroke dimensions of 112.0 x 60.8mm were chosen, allowing big-block-Chevy-sized pistons to freely rev to the skies above. The big ports required to flow air at peak are so big that torque in the midrange suffers. From 4,000 to 8,500 rpm, the EBR makes between 5 and 18 more pound-feet of torque and a similar amount of additional horsepower. Big ports are great for peak power, and the Ducati peaks about 6 hp higher, but when the pistons move more slowly at mid-revs, so must the intake flow, generating less vigorous in-cylinder turbulence that is essential for fast, efficient combustion.

EBR chose less peak-power-

oriented dimensions of 106.0 x 67.5mm and reasoned that because street riders spend most of theirtime in the midrange, that was where most of the engineering should go. They decided to try opening one of each pair of intake valves a bit early, giving flow entering the cylinder an initial circular motion. It took time and a stack of experimental cams to get this right, but the dyno shows that it works: Axial swirl keeps combustion brisk in the midrange, not letting torque sag. Yes, professional racers can go fast on bikes with peaky power, but it’s easier for pros and street riders alike to lap quickly and confidently with a wider band and meatier midrange. Going fast with peaky power requires you to do everything perfectly. For some, that is a welcome challenge. For many others, it interferes with the fun. CUM

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontKnow Thy Enemy

July 2014 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

July 2014 -

Ignition

IgnitionMassimo Tamburini, 1943-2014

July 2014 By Bruno Deprato -

Ignition

IgnitionKevin Schwantz Rates Marc Marquez

July 2014 By Matthew Miles -

Ignition

IgnitionCw 25 Years Ago July 1989

July 2014 By Mark Hoyar -

Ignition

IgnitionLiving the Part

July 2014 By Kevin Cameron