LIVING THE PART

TDC

THE CULTURAL PHENOMENON OF MAN AND AMERICAN MOTORCYCLE

KEVIN CAMERON

Why is Harley-Davidson the number-one selling motorcycle brand in the US? No, I don't want

to start an argument—there already have been enough. No deep analysis is required to show that many people don't buy motorcycles off a spec sheet. We can agree that Harleys are heavy, that their handling is unique, and that their performance is something unto itself— generally not to be directly compared with anything else.

Any business-school marketing course will include H-D’s success story—how it came back from the AMF years (back from the dead, nearly), ransomed itself, rationalized production, and embarked on a radical course of lifestyle marketing that continues to be uniquely successful.

One American problem that Harley addresses is masculinity. Men are no longer the sole provider in many American families, going to the plant to bring home the bacon. I certainly remember the stand-down of NASA’s Apollo Program in the early 1970s, when thousands of highly educated, experienced career engineers were “let go” in that giant budget reduction. Off they went to new careers—perhaps as Carvel-stand operators—trading in the Buck Rogers drama of, “We have ignition,” for, “Sprinkles on that extralarge twist?” Paul Bunyan, mysteriously replaced by dehydrated squirrel hormones.

In her excellent book Stiffed, sociologist Susan Faludi describes the plight of outof-work aircraft engineers during the “era of consolidation” (Douglas became McDonnell-Douglas, and then both became just a Boeing division). Wearing their Douglas jackets, they gathered for coffee before attending job fairs or realestate license training. From necessity their wives had become de facto sole providers. Yet so solid seemed the work

world in which these men grew up that they remained sure for years that any day they’d be called back to the drawing board, to the conference room, to flight test. In fact, they no longer quite knew who they were or what the point of their lives was. Old certainties had lost their moxie. They needed help, and so did their children. American motorcycles are an unchanging island of manly certainty in the river of time. Check out the colors and chrome, straight from a better time.

Then there’s the question of doing the lap times. If you unload a brand-new Ducati 1199 Superleggera at a trackday (your wallet correspondingly lightened), people might look with interest at the bike but not at you—until you show you can do the machine justice with your lap times. In the early 1980s, plenty of riders showed up for the AMA National at Loudon, New Hampshire, on TZ750 Yamahas—but frankly, all but a few of them would have lapped quicker on 250s. The 750 was just too much motorcyclefrightening. And compared with today’s 200-hp literbikes, that once-fearsome TZ has become just another quaint vintage bike on little hard tires. As a result, many riders today are secretly humiliated by their wonderful, capable 21st-century machines. Because they can’t ride them anywhere close to their limits. Who can?

But with an American motorcycle? Big difference. In this world, doing the lap times is showing up. You are cool, you are the scene, not part of it. An elbow on the ground is irrelevant, even laughable. You sit at the stoplight with a 100-inch engine rumbling and the handlebars shaking. How can that guy control that mighty machine? Theater! The light changes, you thunder off. You may very well be just on your way to a latte, but your departure is pure Easy Rider.

Marketeers play games with our natures, changing shapes and colors to send particular messages that will seep between us and our money like mold release, allowing it to separate from us. The Rolling Stones all those years ago sang, “But he can’t be a man/ ’cause he doesn’t smoke/the same cigarettes as me.” None of us want to look in the bathroom mirror one morning and see no one, nothing but the wall behind. In a world of stock prices jacked by firing 30,000 GE or IBM employees at a crack, we need identity that a Douglas jacket and 25-year pin can’t deliver. American motorcycles come with nationalism attached. American motorcycles are a metaphor for this nation at its best, heavy with momentum, going somewhere, confidently doing important things, and not being quiet about it. Try that on your Tohatsu.

BY THE NUMBERS

260,471 HARLEY-DAVIDSONS SOLD WORLDWIDE IN 2013

140 PEAK HORSEPOWER OF THE BEST TZ75Os

17,000 POUNDS OF FORCE FROM MV SHOP PRESS

Lest you think I’m headed for tats and chain wallet, have no fear. I’m still anchored somewhere in the Handbook of Chemistry and

Physics, trying to make sense of how machines work. But I also need to know how the American motorcycle phenomenon works. It’s too big to ignore.

Looking at history, we see the US created the petroleum industry and so for years enjoyed its plenty—and its lowest prices. Our cars and our bikes were big because we alone in this world could afford the fuel to run them. They were heavy because the Lincoln Highway and all those hastily made Midwestern survey roads were rough, and more steel was the reliable antidote to failure. The game began with big, slow-turning engines, and there was never a good reason to change because those engines were ideally suited to move all that metal. So the pattern has remained, and its marketing has been brilliant. The nature of the American motorcycle has grown

out of the nature of America.

Motorcycling is diverse. American motorcycles are popular but can’t be everyone’s choice.

The athletic rider is found on a sportbike or dirt bike, delighting in quick response. There are engines smoother than big V-twins, making room for other architectures and more cylinders. Those who covertly dream of reaching Patagonia ride to work on tippy-toe-tall 500-pound adventure bikes. Racers race or take care to look the part. Scooterists scoot, their treasured on-board storage bulging. Italian bikes are elegance, art. English ones have too many fasteners, that charming bulbous look, like a 1950s Hawker “Hunter” aircraft. Japanese bikes show the dizzy heights that incremental engineering can reach. German bikes? Lirst principles meet age-old tradition, with plenty of press-fits.

The choice is yours. ETU

AMERICAN MOTORCYCLES AREA METAPHOR FORTHIS NATION AT ITS BEST, HEAVY WITH MOMENTUM, GOING SOMEWHERE, CONFIDENTLY DOING IMPORTANT THINGS, AND NOT BEING QUIET ABOUTIT.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontKnow Thy Enemy

July 2014 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

July 2014 -

Ignition

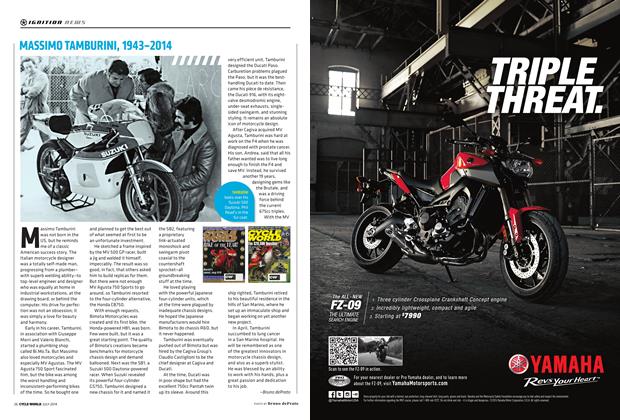

IgnitionMassimo Tamburini, 1943-2014

July 2014 By Bruno Deprato -

Ignition

IgnitionKevin Schwantz Rates Marc Marquez

July 2014 By Matthew Miles -

Ignition

IgnitionCw 25 Years Ago July 1989

July 2014 By Mark Hoyar -

Tests/reviews

Tests/reviewsTwins Not Twins

July 2014 By Kevin Cameron