GOOD VIBRATIONS

IGNITION

LEANINGS

BSAs, BONNEVILLES AND DICK MANN

PETER EGAN

When I heard my friend Rob was going to haul his T-shirt trailer to the Madison BMW Club's Great River Road Rally in Soldiers Grove, Wisconsin, I decided to ride up there for a visit. It was supposed to be a beautiful day, and the loop from our house to Soldiers Grove and back takes you through 250 miles of green, hilly farm country, with lots of curves, ridges and hollows. If we were a little closer to the Appalachians, they’d be called “hollers” and Dolly Parton would live there. Alas, we don’t and she doesn’t. Nice roads nevertheless.

My one reservation in visiting the BMW rally was that I don’t have a BMW right now. I’ve owned four but am sadly Boxerless at the moment. As a soulful alternative, I thought I’d take something British, so it was a toss-up between my 2008 Triumph T100 Bonneville or recently refurbished 1969 BSA 441 Victor Special.

The burning philosophical question was: Should I take my Triumph and buy a BSA shirt from Rob, or ride the BSA and buy a Triumph T-shirt? I already have about 12 Triumph shirts and no BSA shirts, so the decision was easy. I’ve long admired those shirts with the winged red BSA emblem across the front, as they always make me think of Dick Mann in his prime, which is a good memory.

Of course, there was another obvious reason to pick the Triumph: It’s a modern bulletproof bike with faultless electrics, a smooth counterbalanced crank and a top speed above too mph, and the BSA is not.

I’ve been riding the Victor quite a bit lately, mostly on those short evening jaunts where you chuff around the countryside and watch the sun go down—making sure, of course, to get home before dark.

The bike is kind of a vampire in reverse; it has a special darkness-sensing headlight that starts to flicker and dim just about moonrise, as if it wants to fold its cape and return to the crypt for the night. So most of these twilight rides last only about 25 miles, which I’ve found to be just the right amount of time to spend on the bike, anyway.

Why?

Well, vibration.

An old Cycle World road test from April of 1966 shows the Victor running the quartermile in 15.5 seconds at 81 mph, with a theoretical top speed at redline (6500 rpm) in fourth gear of 93 mph. This was on a brand-new test bike, of course, and mine is old, but I would no more attempt to squeeze 81 mph out of this engine than drop our favorite cat out of an airplane to see if it lands on its feet. Not without a Carrillo rod, anyway. As for 93 mph, well, it’s like hearing your Chevy Sonic will hit 215 mph, if you can just reach redline. No need to go there.

I’ve discovered this bike is happiest at about an indicated 45 mph. And I say “indicated” because the speedometer does seem to be reading slow, so it might be 50 mph, for all I know. Smiths instruments have always been vague, which some would say is a serious shortcoming in a precision instrument designed to measure things. But I would estimate the BSA’s “sweet spot” is somewhere around 50 mph. Beyond that, it starts to vibrate in ways you instinctively know can’t be good for coil brackets, light bulbs, fender stays and other metal parts. Or your kidneys.

This bike, after all, was designed as a street-legal scrambler, so it’s geared (and cammed) for flexibility in the dirt rather than droning down the Interstate. It is, in fact, that easy torque and spare, dirtbike simplicity that define its character and make it such a charming cruiser on our quiet farm roads.

But it does vibrate some, even in that sweet spot. When I first got the BSA running last month, I rode it six miles into the town of Stoughton to put some fresh fuel in the tank, and when I came home, I told Barb proudly, “I made it all the way into Stoughton and back with no trouble!”

She smiled an uncertain smile, not quite sure what all the fuss was about.

BY THE NUMBERS

NUMBER OF LOOSE BOLTS, FATIGUE CRACKS AND BURNEDOUT HEADLIGHT BULBS ON MY 1975 HONDA 400F AFTER A SEASON OF BOX-STOCK ROADRACING FOLLOWED BY A 2000-MILE TRIP DOWN THE MISSISSIPPI TO NEW ORLEANS AND BACK

NUMBER OF FOOTPEG AND FLOORBOARD RUBBERS THAT JITTERED OFF THE NEW H-D FLH HERITAGE THAT BARB AND I RODE UP AND DOWN THE WEST COAST IN 1981

I then parked the Victor in the workshop next to my 1976 Honda CB~~o Four, and, contemplating the two of them, had to grin at the contrast. Last time I took the 550 out for a ride, I came home and told Barb, "I would honestly ride this thing to California and back without hesitation."

And now, I was proud to have made it home from the gas station.

Hardly a fair comparison, of course as these bikes, though close in age, were designed in different parts of the 20th century. Still, the most glaring difference between them is really just the electric smoothness of the Honda FOUL I've often thought the greatest single technical advance in motorcycle design in my lifetime (other than brakes that actually retard your speed) has been the conquest of destructive vibration.

BMW seems to have been the first company to tackle this problem at its root, Max Friz's Boxer Twin having a natural balance that produced only a rather pleasant rocking motion at idle. I haven’t ridden any of the historic longitudinal inline-Fours, such as the Henderson or the Indian, but I’m told by those who have that they’re quite smooth. After that, we have a mixed bag of jitters with various Singles and Twins, most fixes revolving (literally) around rubber engine mounts.

Other than Honda’s rediscovery of the inline-Four (and sublime Six), we really didn’t make much progress until Yamaha came up with its “Omni-Phase Balancer” for its 500CC and 750CC four-stroke Twins in 1973.1 remember a great debate about this at the time. Some thought this was “cheating” because these chain-driven dual counterbalance shafts added complexity to the bike without furthering its measurable performance. What would we have next? Cannibalism in our schools? The end was near.

Well, two of my favorite modern bikes, the Bonneville and the Suzuki DR650, have counterbalancers in them, and I don’t mind a bit. I can’t see or hear them, they never wear out, and my hands and feet aren’t humming like tuning forks at the end of a ride. Headlight filaments light up the night and the exhaust pipes never fall off.

And I had a serene 250-mile Bonneville ride to Soldiers Grove, a beautiful little town in the Kickapoo Valley, swarming with lots of those naturally smooth BMWs. And Rob gave me a T-shirt with that classic winged BSA logo across the chest.

Now, I look just like Dick Mann, but without the riding talent.

Or that tingling sensation in my hands and feet. When I got home, I still felt good enough to take a 25mile ride on my BSA. Wearing the T-shirt, just before dark.

THE B5A HAS A SPECIAL DARKNESSSENSING HEADLIGHT THAT STARTS TO FLICKER AND DIM JUST ABOUT MOONRISE.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Ten Rest

September 2013 By Mark Hoyer -

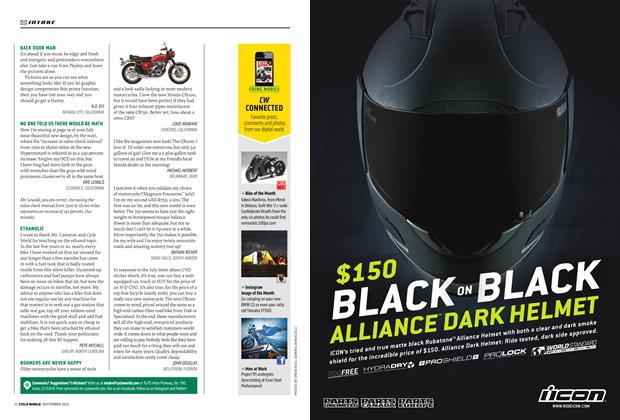

Intake

IntakeIntake

September 2013 -

Going Mobile

September 2013 -

Ignition

IgnitionSound And Fury Carb Your Enthusiasm

September 2013 By John Burns -

Ignition

IgnitionCw 25 Years Ago September, 1988

September 2013 By Blake Conner -

Ignition

IgnitionOn the Record Troy Bayliss

September 2013 By Don Canet