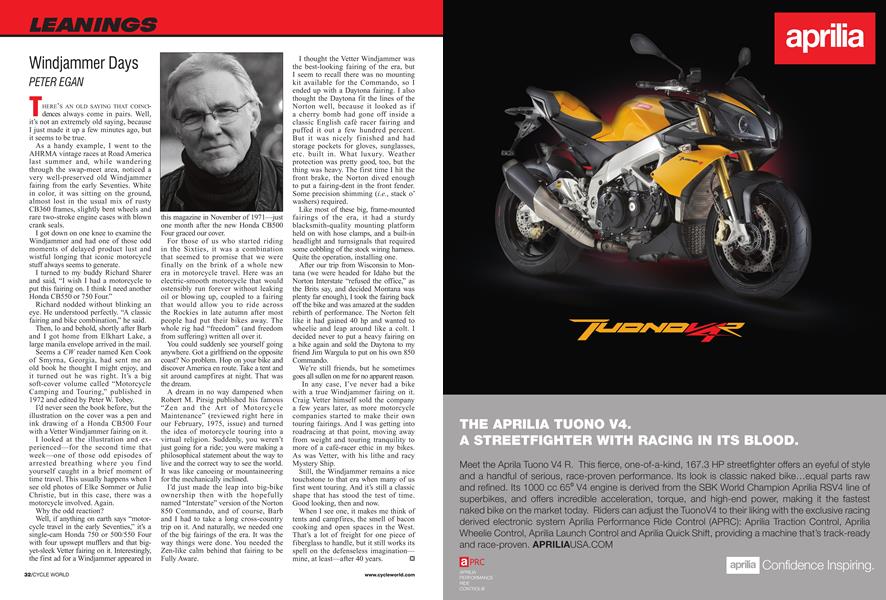

Windjammer Days

LEANINGS

PETER EGAN

THERE’S AN OLD SAYING THAT COINCIdences always come in pairs. Well, it’s not an extremely old saying, because I just made it up a few minutes ago, but it seems to be true.

As a handy example, I went to the AHRMA vintage races at Road America last summer and, while wandering through the swap-meet area, noticed a very well-preserved old Windjammer fairing from the early Seventies. White in color, it was sitting on the ground, almost lost in the usual mix of rusty CB360 frames, slightly bent wheels and rare two-stroke engine cases with blown crank seals.

I got down on one knee to examine the Windjammer and had one of those odd moments of delayed product lust and wistful longing that iconic motorcycle stuff always seems to generate.

I turned to my buddy Richard Sharer and said, “I wish 1 had a motorcycle to put this fairing on. I think I need another Honda CB550 or 750 Four.”

Richard nodded without blinking an eye. He understood perfectly. “A classic fairing and bike combination,” he said.

Then, lo and behold, shortly after Barb and 1 got home from Elkhart Lake, a large manila envelope arrived in the mail.

Seems a CW reader named Ken Cook of Smyrna, Georgia, had sent me an old book he thought I might enjoy, and it turned out he was right. It’s a big soft-cover volume called “Motorcycle Camping and Touring,” published in 1972 and edited by Peter W. Tobey.

I’d never seen the book before, but the illustration on the cover was a pen and ink drawing of a Honda CB500 Four with a Vetter Windjammer fairing on it.

I looked at the illustration and experienced—for the second time that week—one of those odd episodes of arrested breathing where you find yourself caught in a brief moment of time travel. This usually happens when I see old photos of Elke Sommer or Julie Christie, but in this case, there was a motorcycle involved. Again.

Why the odd reaction?

Well, if anything on earth says “motorcycle travel in the early Seventies,” it’s a single-cam Honda 750 or 500/550 Four with four upswept mufflers and that bigyet-sleek Vetter fairing on it. Interestingly, the first ad for a Windjammer appeared in this magazine in November of 1971—just one month after the new Honda CB500 Four graced our cover.

For those of us who started riding in the Sixties, it was a combination that seemed to promise that we were finally on the brink of a whole new era in motorcycle travel. Here was an electric-smooth motorcycle that would ostensibly run forever without leaking oil or blowing up, coupled to a fairing that would allow you to ride across the Rockies in late autumn after most people had put their bikes away. The whole rig had “freedom” (and freedom from suffering) written all over it.

You could suddenly see yourself going anywhere. Got a girlfriend on the opposite coast? No problem. Hop on your bike and discover America en route. Take a tent and sit around campfires at night. That was the dream.

A dream in no way dampened when Robert M. Pirsig published his famous “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” (reviewed right here in our February, 1975, issue) and turned the idea of motorcycle touring into a virtual religion. Suddenly, you weren’t just going for a ride; you were making a philosophical statement about the way to live and the correct way to see the world. It was like canoeing or mountaineering for the mechanically inclined.

I’d just made the leap into big-bike ownership then with the hopefully named “Interstate” version of the Norton 850 Commando, and of course, Barb and I had to take a long cross-country trip on it. And naturally, we needed one of the big fairings of the era. It was the way things were done. You needed the Zen-like calm behind that fairing to be Fully Aware.

I thought the Vetter Windjammer was the best-looking fairing of the era, but I seem to recall there was no mounting kit available for the Commando, so I ended up with a Daytona fairing. I also thought the Daytona fit the lines of the Norton well, because it looked as if a cherry bomb had gone off inside a classic English café racer fairing and puffed it out a few hundred percent. But it was nicely finished and had storage pockets for gloves, sunglasses, etc. built in. What luxury. Weather protection was pretty good, too, but the thing was heavy. The first time I hit the front brake, the Norton dived enough to put a fairing-dent in the front fender. Some precision shimming (i.e., stack o’ washers) required.

Like most of these big, frame-mounted fairings of the era, it had a sturdy blacksmith-quality mounting platform held on with hose clamps, and a built-in headlight and turnsignals that required some cobbling of the stock wiring harness. Quite the operation, installing one.

After our hip from Wisconsin to Montana (we were headed for Idaho but the Norton Interstate “refused the office,” as the Brits say, and decided Montana was plenty far enough), I took the fairing back off the bike and was amazed at the sudden rebirth of performance. The Norton felt like it had gained 40 hp and wanted to wheelie and leap around like a colt. I decided never to put a heavy fairing on a bike again and sold the Daytona to my friend Jim Wargula to put on his own 850 Commando.

We’re still friends, but he sometimes goes all sullen on me for no apparent reason.

In any case, I’ve never had a bike with a true Windjammer fairing on it. Craig Vetter himself sold the company a few years later, as more motorcycle companies started to make their own touring fairings. And I was getting into roadracing at that point, moving away from weight and touring tranquility to more of a café-racer ethic in my bikes. As was Vetter, with his lithe and racy Mystery Ship.

Still, the Windjammer remains a nice touchstone to that era when many of us first went touring. And it’s still a classic shape that has stood the test of time. Good looking, then and now.

When I see one, it makes me think of tents and campfires, the smell of bacon cooking and open spaces in the West. That’s a lot of freight for one piece of fiberglass to handle, but it still works its spell on the defenseless imagination— mine, at least—after 40 years. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAmusement Parks And the Leisure Gap

May 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

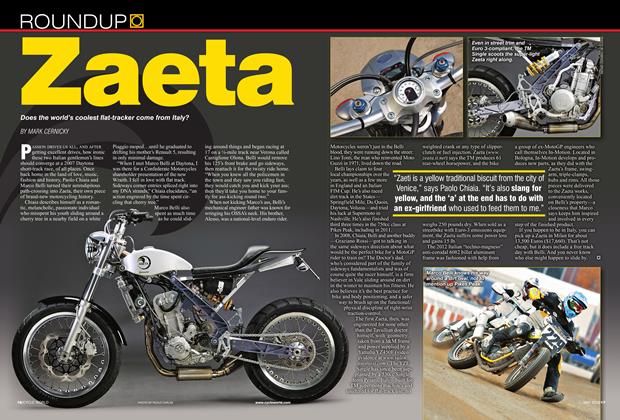

RoundupZaeta

May 2012 By Mark Cernicky -

Roundup

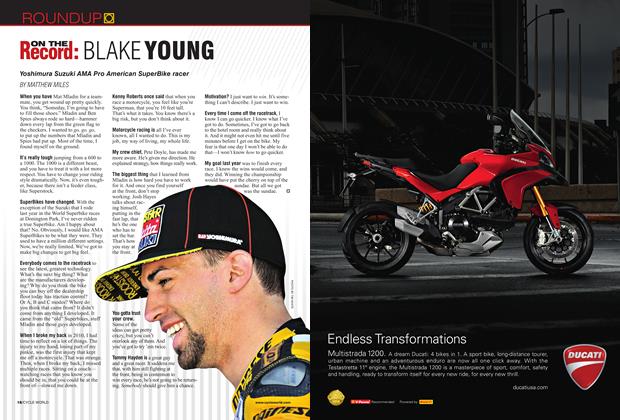

RoundupOn the Record: Blake Young

May 2012 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupRide Faster. Ride Safer.

May 2012 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago May 1987

May 2012 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupIs the Ducati For Everyone?

May 2012