Two-stroke Resurrection

ROUNDUP

Can two-stroke engines make a comeback?

STEVE ANDERSON

DURING OUR RECENT VISIT TO HUSQVARNA ("REMAKING HUSQVARNA," SEPTEMBER), company executives said they have a high-tech two-stroke, likely directly injected, in their near-term product plan. At KTM, a tech-services manager claims that the company has a direct-injection two-stroke under test, essentially ready to go when there's a need in the marketplace. Other companies drop hints that they're reevaluating their prior decisions to go 100-percent four-stroke with their dirtbike lines. Are two-stroke engines on the verge of a revival?

The answer to that question is yes, at least to a limited extent. Two-stroke engines in motorcycle applications went away for several reasons. First, they had higher levels of hydrocarbon and carbon-monoxide exhaust emissions than four-stroke engines, and reducing those emissions couldn't readily piggyback

on all the work that had been expended by the automotive industry on car en gines. Second, they also had worse fuel economy. But, third, and worst of all, they were perceived as "non-green," smoke-emitting, image disasters. Major companies such as Honda made the decision to stop producing two-strokes, and racing organizations went along by changing rules to penalize or eliminate them. Four-strokes, with a few excep tions, took over off-road motorcycling, even in closed-course competition. But there was a cost to that. The new four-stroke motocrossers were more expensive and much more maintenanceintensive than the two-stroke machines they replaced. They also tended to have exhaust sound that was offensive for longer distances, putting pressure on motocross "..,. tracks in some loca tions to quiet down or be shut down. And some riders simply liked two-stroke engine charac teristics better. But two other off-road activities also faced the same issues and

with different solutions. Both the out board-marine industry and the snowmoti bile industry initially attempted to make c the switch to four-stroke engines but it were met with customer resistance to c the heavier and more-expensive powero plants that resulted. This opposition led "~ to a new generation of cleaner, directi~ injected two-stroke engines that meet si respective emissions requirementsi~ though these are notably less strict than (1 those for on-road vehicles. The most recent example would be Ski-Doo's E-TEC (ecotech) 800cc Rotax Twin, r~ which puts out 155 horsepower-more F power per cc than BMW'S S1000RR, a the current king of literbike horsepower. c Unlike Bimota's abortive 1997 Vdue, ti a two-stroke with conventional injecn tors squirting into the transfer ports-a c design that never really worked-the outboard and snowmobile - s: engines are well-developed - -and reliable.

Now that such~h nology is available for motorcycle engines, some players in the -industry are taking another look, since direct fuel injection Ii.' e has the potential to drastically reduce emis4 sions. Two-stroke engines, which combine the intake and exhaust cycles to a degree not pos sible in four-strokes, have an issue with fresh charge coming through their transfer

ports and flowing directly out the exhaust W port, dramatically raising hydrocarbon dii emissions-and not helping fuel econin~ omy, either. Direct injection allows fuel a to be injected into the cylinder just as the ca piston is rising to seal the exhaust port, th~ preventing this direct short-circuiting. oil Similarly, conventional two-stroke enrei gines at very low loads may actually be on operating on four-, sixor eight-cycle uf processes. This is because so much fi~ exhaust gas is retained in the cylinder go at small throttle openings that it may take several crankshaft revolutions to clear the cylinder sufficiently to create a combustible mixture. It's far better to operate at low loads with intake air only (no fuel lost out the exhaust) and the in jection programmed to add fuel only on the combustible cycle. When used with engines designed for them, direct injec tion systems allow much lower baseline emissions before any after-treatment system (catalytic converter) is added, and they can improve fuel economy by as much as 50 percent.

In addition to direct fuel injec tion, there are other technologies that can help. Two decades ago, Honda introduced a 250cc, two-stroke motor cycle engine for a Japanese-marketonly dual-purpose bike that utilized "Activated Radical Combustion." This is a technology that has since been wellstudied by the automotive industry and is more commonly known as HCCI (Homogenous Charge Compression Ignition), a combustion process that requires no spark but uses gasoline rather than diesel fuel. In Honda's 250, HCCI combustion was maintained from about eight to 50 percent load, with conventional spark ignition used at both the high and low end of the engine load range. The benefit was far more stable combustion (no sixor eight-cycling) when HCCI was operating, lower emis sions and-according to those who rode j it-a two-stroke that felt as if it had the smooth power of a four-stroke. . Honda's patents have since expired.

While there is little doubt that technology exists to create off-road two-stroke ` motorcycle engines that meet current and future EPA or California green-sticker offroad emissions requirements, the question remains whether sufficient technology exists to create street-legal two-stroke en gines as in, say, a 300cc dual-purpose bike making 40-plus horsepower. This would require one of the available direct-injection technologies, an oxidiz ing catalyst in the exhaust and, likely, a direct lubrication system that feeds carefully controlled amounts of oil to the main and rod bearings to minimize oil usage. While that question currently remains unanswered, there is at least one top engine designer at a major man ufacturer who believed it was possible five years ago. The technology has only gotten better since.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

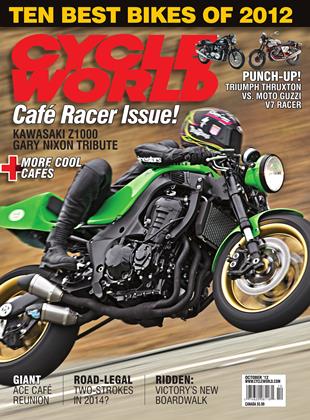

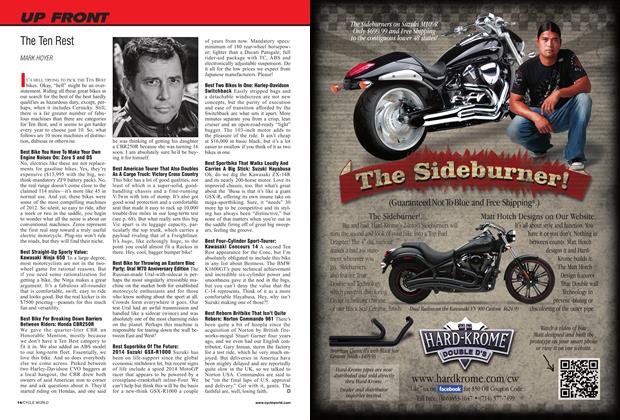

ColumnsUp Front

October 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Round Up

Round Up25 Years Ago October 1987

October 2012 By Don Canet -

Round Up

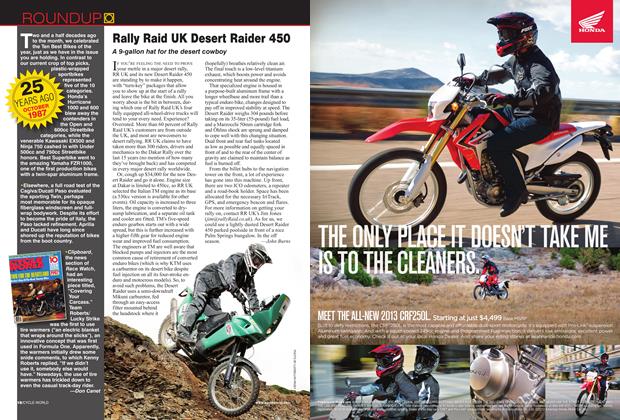

Round UpRally Raid Uk Desert Raider 450

October 2012 By John Burns -

Roundup

RoundupOn the Record: Paolo Ciabatti

October 2012 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

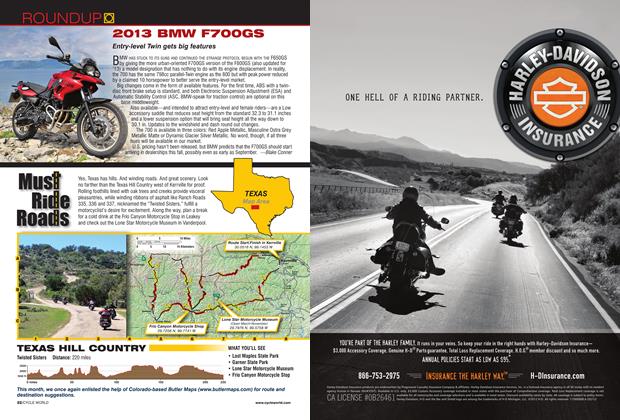

Roundup2013 Bmw F700gs

October 2012 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

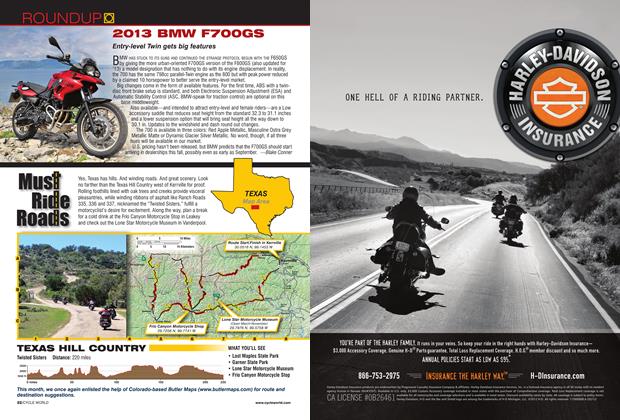

RoundupMust Ride Roads

October 2012