Triumph Speedmaster

QUICKRIDE

The Triumph cruiser, right-sized?

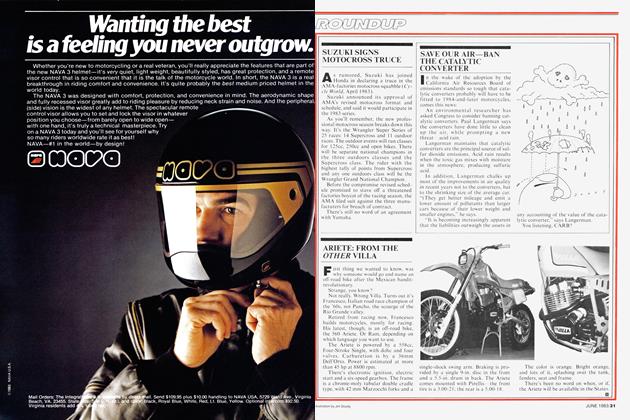

"ENTRY-LEVEL?” AS A DUDE who’s been riding motorcycles for three decades now, am I not supposed to like ones labeled “entry-level”? I guess because sportbikes are my favorites, smaller and lighter to me generally means better, a mindset I can’t entirely shake when I ride cruisers.

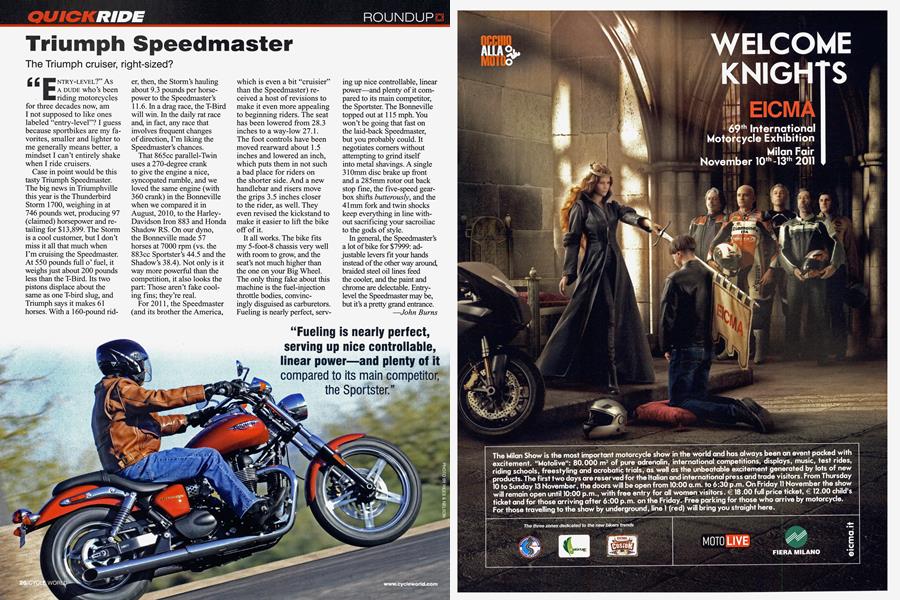

Case in point would be this tasty Triumph Speedmaster. The big news in Triumphville this year is the Thunderbird Storm 1700, weighing in at 746 pounds wet, producing 97 (claimed) horsepower and retailing for $13,899. The Storm is a cool customer, but I don’t miss it all that much when I’m cruising the Speedmaster. At 550 pounds full o’ fuel, it weighs just about 200 pounds less than the T-Bird. Its two pistons displace about the same as one T-bird slug, and Triumph says it makes 61 horses. With a 160-pound rider, then, the Storm’s hauling about 9.3 pounds per horsepower to the Speedmaster’s 11.6. In a drag race, the T-Bird will win. In the daily rat race and, in fact, any race that involves frequent changes of direction, I’m liking the Speedmaster’s chances.

That 865cc parallel-Twin uses a 270-degree crank to give the engine a nice, syncopated rumble, and we loved the same engine (with 360 crank) in the Bonneville when we compared it in August, 2010, to the HarleyDavidson Iron 883 and Honda Shadow RS. On our dyno, the Bonneville made 57 horses at 7000 rpm (vs. the 883cc Sportster’s 44.5 and the Shadow’s 38.4). Not only is it way more powerful than the competition, it also looks the part: Those aren’t fake cooling fins; they’re real.

For 2011, the Speedmaster (and its brother the America,

which is even a bit “cruisier” than the Speedmaster) received a host of revisions to make it even more appealing to beginning riders. The seat has been lowered from 28.3 inches to a way-low 27.1.

The foot controls have been moved rearward about 1.5 inches and lowered an inch, which puts them in not such a bad place for riders on the shorter side. And a new handlebar and risers move the grips 3.5 inches closer to the rider, as well. They even revised the kickstand to make it easier to lift the bike off of it.

It all works. The bike fits my 5-foot-8 chassis very well with room to grow, and the seat’s not much higher than the one on your Big Wheel. The only thing fake about this machine is the fuel-injection throttle bodies, convincingly disguised as carburetors. Fueling is nearly perfect, serv-

ing up nice controllable, linear power—and plenty of it compared to its main competitor, the Sportster. The Bonneville topped out at 115 mph. You won’t be going that fast on the laid-back Speedmaster, but you probably could. It negotiates comers without attempting to grind itself into metal shavings. A single 310mm disc brake up front and a 285mm rotor out back stop fine, the five-speed gearbox shifts butterously, and the 41mm fork and twin shocks keep everything in line without sacrificing your sacroiliac to the gods of style.

In general, the Speedmaster’s a lot of bike for $7999: adjustable levers fit your hands instead of the other way around, braided steel oil lines feed the cooler, and the paint and chrome are delectable. Entrylevel the Speedmaster may be, but it’s a pretty grand entrance.

—John Burns

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

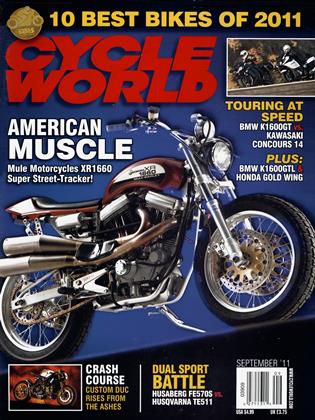

Up FrontThe Ten Rest 2011

SEPTEMBER 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

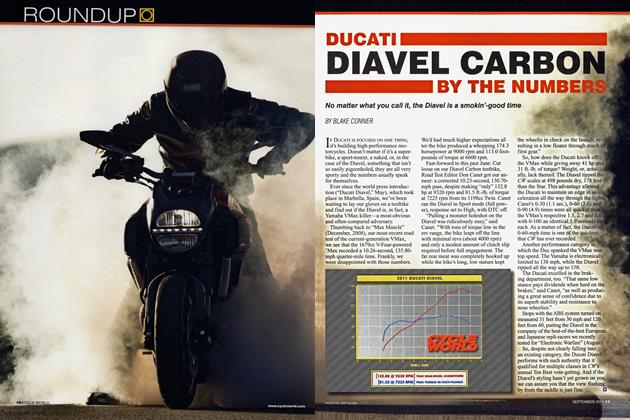

RoundupDucati Diavel Carbon By the Numbers

SEPTEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

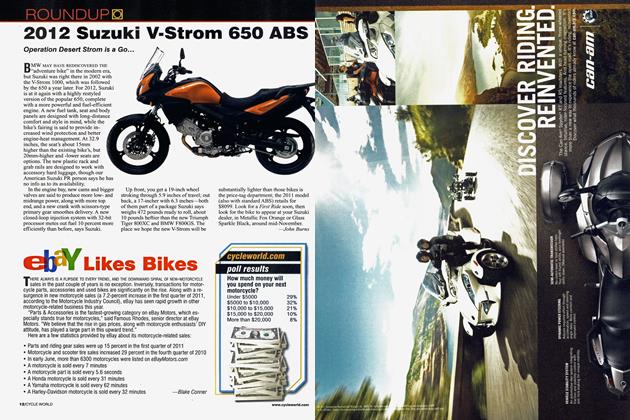

Roundup2012 Suzuki V-Strom 650 Abs

SEPTEMBER 2011 By John Burns -

Roundup

RoundupEbay Likes Bikes

SEPTEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago September 1986

SEPTEMBER 2011 By John Burns -

Roundup

RoundupMv Agusta F3

SEPTEMBER 2011 By Bruno Deprato