Desmodreamic

Ducati camshafts and the question of degrees

The much-publicized new role of electronics in shaping engine power delivery has masked old truths. More than anything else, cam timing and lift are what shape the “natural engine” that lies beneath today’s electronic smoothing of power curves.

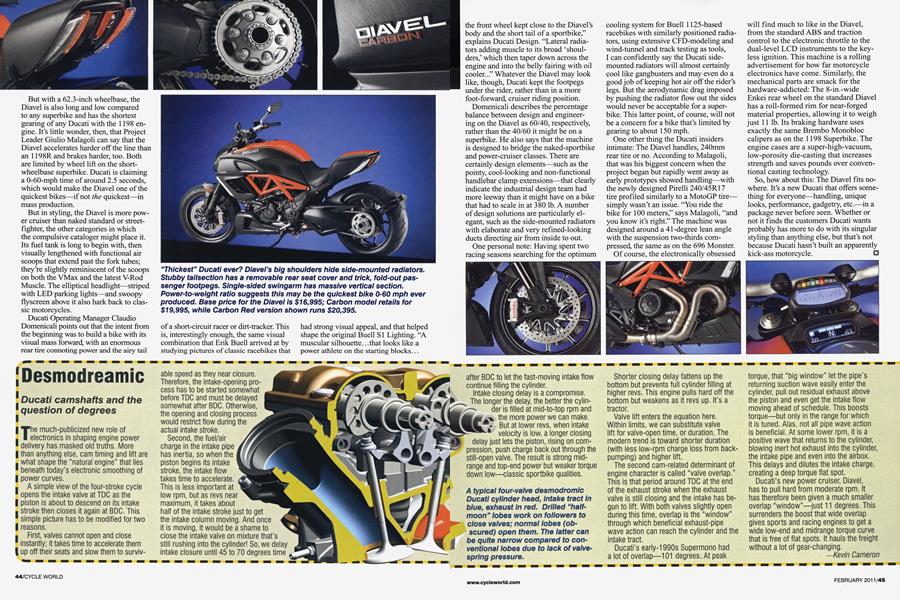

A simple view of the four-stroke cycle opens the intake valve at TDC as the piston is about to descend on its intake stroke then closes it again at BDC. This simple picture has to be modified for two reasons.

First, valves cannot open and close instantly; it takes time to accelerate them up off their seats and slow them to surviv-

able speed as they near closure.

Therefore, the intake-opening process has to be started somewhat before TDC and must be delayed somewhat after BDC. Otherwise, the opening and closing process would restrict flow during the actual intake stroke.

Second, the fuel/air charge in the intake pipe has inertia, so when the piston begins its intake stroke, the intake flow takes time to accelerate.

This is less important at low rpm, but as revs near maximum, it takes about half of the intake stroke just to get the intake column moving. And once it is moving, it would be a shame to close the intake valve on mixture that’s still rushing into the cylinder! So, we delay intake closure until 45 to 70 degrees time after BDC to let the fast-moving intake flow continue filling the cylinder. Intake closing delay is a compromise. The longer the delay, the better the cylinder is filled at mid-to-top rpm and g* the more power we can make. But at lower revs, when intake velocity is low, a longer closing delay just lets the piston, rising on compression, push charge back out through the still-open valve. The result is strong midrange and top-end power but weaker torque down low—classic sportbike qualities. Shorter closing delay fattens up the bottom but prevents full cylinder filling at higher revs. This engine pulls hard off the bottom but weakens as it revs up. It’s a tractor.

Valve lift enters the equation here.

Within limits, we can substitute valve lift for valve-open time, or duration. The modern trend is toward shorter duration (with less low-rpm charge loss from backpumping) and higher lift.

The second cam-related determinant of engine character is called “valve overlap.” This is that period around TDC at the end of the exhaust stroke when the exhaust valve is still closing and the intake has begun to lift. With both valves slightly open during this time, overlap is the “window” through which beneficial exhaust-pipe wave action can reach the cylinder and the intake tract.

Ducati’s early-1990s Supermono had a lot of overlap—101 degrees. At peak torque, that “big window” let the pipe’s returning suction wave easily enter the cylinder, pull out residual exhaust above the piston and even get the intake flow moving ahead of schedule. This boosts torque—but only in the range for which it is tuned. Alas, not all pipe wave action is beneficial. At some lower rpm, it is a positive wave that returns to the cylinder, blowing inert hot exhaust into the cylinder, the intake pipe and even into the airbox. This delays and dilutes the intake charge, creating a deep torque flat spot.

Ducati’s new power cruiser, Diavel, has to pull hard from moderate rpm. It has therefore been given a much smaller overlap “window”—just 11 degrees. This surrenders the boost that wide overlap gives sports and racing engines to get a wide low-end and midrange torque curve that is free of flat spots. It hauls the freight without a lot of gear-changing.

Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe “last” Rebuild

FEBRUARY 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

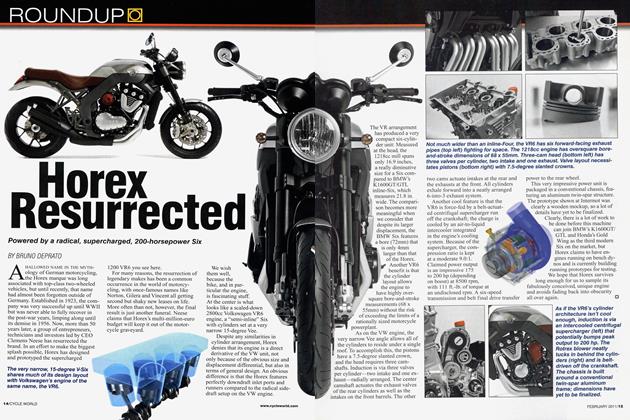

RoundupHorex Resurrected

FEBRUARY 2011 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

Roundup2012 Ducati Superbike

FEBRUARY 2011 By Jeff Roberts -

Roundup

RoundupLittle Hauler

FEBRUARY 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago September 1985

FEBRUARY 2011 By John Burns -

Roundup

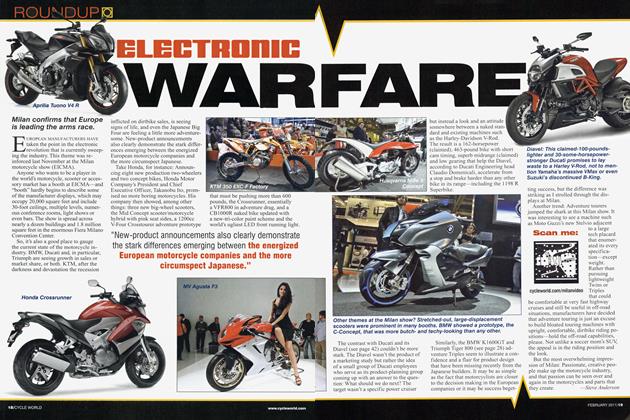

RoundupElectronic War Fare

FEBRUARY 2011 By Steve Anderson