HATCHING A HIGHWAY MACHINE

Ride a CZ to work? It's better than the bus!

Jake Grubb

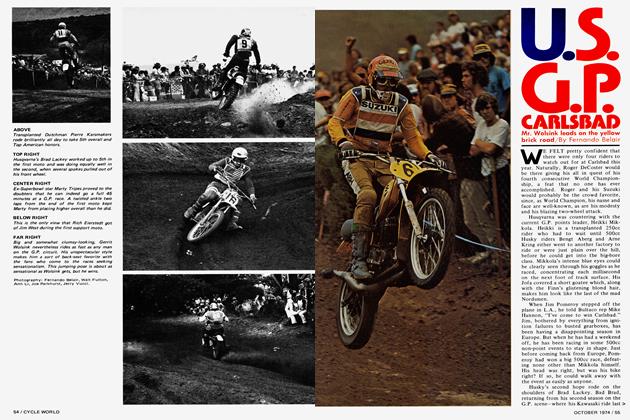

LITTLE MORE than a decade ago there was a trend going on that had people changing almost any kind of motorcycle they owned into something that could be ridden in the dirt:

"Whut yuh do is, yuh git a hammer, a piece uh pipe, a cressunt wrinch, a hacksaw an' a screwdriver. Some wire an' a roll uh racer's tape an' a little bit uh that sticky yella stuff that comes in a tube'll probly help too. Now set that thar bike on the stand an’ flat git to it!

Unscrew the front and back lights from the brackets an ’ cut the whole wire y mess away from the frame. Next

thing is to bob the rear fender. Scratch a mark across it right above where the tail light used to be so’s you know where to cut. Now grab the saw an ’ start hackin ’. After you cut it all the way across make sure to file the edge so it don’t cut somebody.

Then git down an ’ loosen the nut on the rear axle so ’s you can take the rear wheel off. You get rid uh the street tire an’ slap that knobbie on the back. After that yuh jus’ take the baffles out uh the pipes and then put them big handlebars on. Before yuh know it you’ve got a dirt machine! ”

There is a lot less slip-shod modification going on today. In recent years the trend has osmosized into widespread buying of dirt bikes—complete dirt bikes that manufacturers offer as specialized instruments for pure play. Both the industry and the motorcycle owner have become much more sophisticated.

There is no motivation like necessity, however, and the biggest and newest trend is one of compliance with an “energy crisis” that, whether real or perpetrated, is making it damned expensive for people to take part in normal everyday road travel. Present problems of personal transportation, now so familiar to everyone, are hatching a multiplicity of makeshift commuter modes certainly unforeseen by state and local DMVs! While a newly-awakened Yankee ingenuity is scratching its sleepy

head, citizens who need to keep moving are scurrying desperately to adapt.

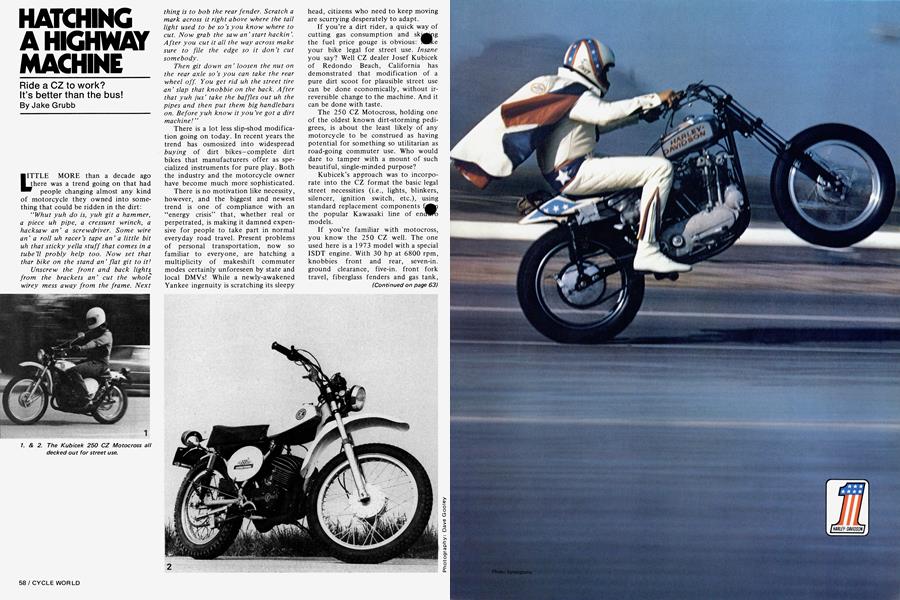

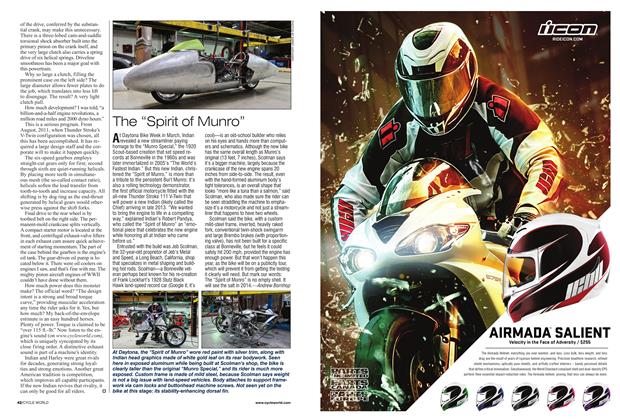

If you’re a dirt rider, a quick way of cutting gas consumption and skkÉkig the fuel price gouge is obvious: WBce your bike legal for street use. Insane you say? Well CZ dealer Josef Kubicek of Redondo Beach, California has demonstrated that modification of a pure dirt scoot for plausible street use can be done economically, without irreversible change to the machine. And it can be done with taste.

The 250 CZ Motocross, holding one of the oldest known dirt-störming pedigrees, is about the least likely of any motorcycle to be construed as having potential for something so utilitarian as road-going commuter use. Who would dare to tamper with a mount of such beautiful, single-minded purpose?

Kubicek’s approach was to incorporate into the CZ format the basic legal street necessities (i.e., lights, blinkers, silencer, ignition switch, etc.), using standard replacement components the popular Kawasaki line of encWR models.

If you’re familiar with motocross, you know the 250 CZ well. The one used here is a 1973 model with a special ISDT engine. With 30 hp at 6800 rpm, knobbies front and rear, seven-in. ground clearance, five-in. front fork travel, fiberglass fenders and gas tank, and a hair-trigger throttle—all at only 227 pounds—it is a high-strung performer. A throttle squirt will instantly lift the front end high over obstructions, the tires will dig dirt (and slip on pavement), the brakes are modest stoppers at best by street standards, and the exhaust note raises a lot of commotion. Kubicek first quelled some of the engine’s rowdy fire by changing the tuned exhaust pipe. The replacement version drops peak engine rpm by 500 revs and widens the powerband. It is smaller in diameter, shorter than the performance pipe, and sweeps clean and close up the left side of the cycle.

(Continued on page 63)

Continued from page 58

Inside the pipe is a silencer and spark arrester from a 350cc F9 Kawasaki that quiets the crackle considerably and also keeps heated carbon particles from straying out the end of the exhaust pipe.

Kubicek moved next into the tire department by removing the knobbies. The rear replacement is a 4.00-18 Barum Trials type; a good street/dirt compromise. On the front is a 3.00-21 Dunlop Trials.

Along with the front tire change, Kubicek also fitted a 350cc F9 hub and brake to the wheel. The Kawasaki internal-expanding brake has additional beef and also incorporates an accurate (and lawful) speedometer drive. Aluminum telescopic front forks remain the same, but British Girling units have been added to the rear because of their superior dampening and convenient adjustability.

Internally, the engine is unchanged. Carburetion has been modified in the form of a 32mm Mikuni concentric, fitted with the intake manifold necessary for the change. This replaces the standard Jikov carburetor, which Kubicek praises. But consistent with popular opinion, he cites the option of an adjustable idle stage, manual choke and easily-changeable jets and float level as being qualities conducive to dependable all-around road performance. The ignition is a single-coil Femsatronic transistor ignition which is dependable, requires less maintenance and produces a more constant spark than a points/condenser system.

The full 65-watt lighting circuit, by Stanley, is common to Kawasaki street and enduro bikes. On the CZ it runs off of a compact six-volt battery that is kept charged by the stock generator.

Bolted to the underside of the fork crown is a simple instrument panel from the small lOOcc Kawasaki G5 Enduro. This includes speedometer, ignition switch and signal lights for neutral, brake light and blinkers. At the handgrips are the switches for lights, horn and turn indicators. These also are from the G5.

Front blinker lights, which are fitted to the handlebars, are from the Kawasaki Fl 1 Enduro, as are the indicators in the rear. Also from the Fll are the semi-oval rear taillight that is mounted on top of the CZ fender (yes, holes had to be drilled), the headlight and the fiberglass air cleaner box. The air cleaner box, incidentally, houses a recleanable Filtron foam rubber element.

Particular attention to detail can be seen in Kubicek’s installation of a “neutral pick-up” from the transmission. He had to split the cases and go into the gearbox to do this. A wire lead travels from the engine to the instrument` panel, where a neutral light flashes and shows when the bike is out of gear.

Further, the front brake lever is wired so that it activates the brake light just as the rear brake does.

Also significant is the Kawasaki choke lever, located on the left handlebar under the switch cluster. Because the Mikuni carburetor has a manual choke and no remote control is really necessary, Kubicek has the choke lever set up to activate the compression release, which is used in the dirt to slow the engine without use of the brakes. This eliminates the clutter of an extra lever.

Lastly, the addition of an aluminum BSA gas tank to the already handsome CZ adds polished beauty. Its capacity and function are little different from those of its CZ equivalent. Again, it is a Kubicek preference.

On the road the CZ is a surprise. Power delivery is smooth and handling is responsive, almost airy. The engine, because of its racy “on or off” disposition, cruises with a slight roughness that is to be expected.

Traction on pavement is adequate with the trials tires. It is an obvious compromise, satisfactory primarily because of the rear Barum, which is especially versatile.

The brakes, which do not fess up to the standards of top notch street bike brakes, work pretty well on this model because of its light weight. It doesn’t take much to stop the CZ.

Low dirt gearing is noticeable but does not hinder cross-town or even freeway travel because of the five-speed gearbox and reasonably wide powerband. Hand controls and electrical switches work with the same efficiency and comfort as those on any new^ÉS Kawasaki.

You still have to kickstart the CZ, you still have to mix the oil with the gas manually, and you still have to warm the engine on a hot plug before screwing in the cold plug for normal riding. The engine produces less punch in the dirt because of the “tamed” exhaust pipe, and you break things like blinkers and running lights if you go down.

These little quirks are not to be avoided. But the bike is still a hot rod in the rough, gets mileage twice that of popular compact cars on the road, and takes up a quarter of the space necessary for an automobile when it comes to parking. The bike is fun and it is useful.

Joe Kubicek will duplicate such a project for others at an approximate cost of $400, depending upon the specifics of a given order. He estimates the cost of doing it yourself at not less t^^ $350, with respect to such variables as the type of bike modified, components chosen, extent of the changes, and who does the work.

Joe is available for serious inquiries at: South Bay Motorcycles, 2001 Artesia Blvd., Redondo Beach, CA 90278. With luck, you’ll catch him between his usual mid-morning wheelies down the boulevard.... 151