The Power of One

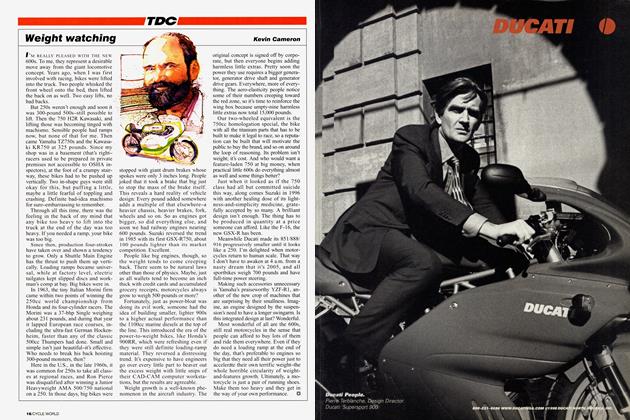

TDC

Kevin Cameron

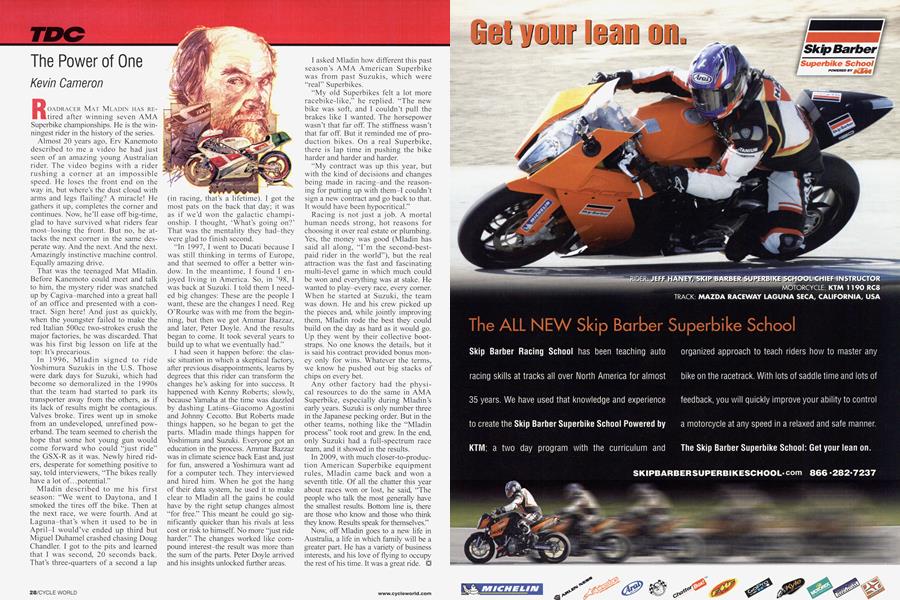

ROADRACER MAT MLADIN HAS REtired after winning seven AMA Superbike championships. He is the winningest rider in the history of the series. Almost 20 years ago, Erv Kanemoto described to me a video he had just seen of an amazing young Australian rider. The video begins with a rider rushing a corner at an impossible speed. He loses the front end on the way in, but where’s the dust cloud with arms and legs flailing? A miracle! He gathers it up, completes the corner and continues. Now, he’ll ease off big-time, glad to have survived what riders fear most-losing the front. But no, he attacks the next corner in the same desperate way. And the next. And the next. Amazingly instinctive machine control. Equally amazing drive.

That was the teenaged Mat Mladin. Before Kanemoto could meet and talk to him, the mystery rider was snatched up by Cagiva-marched into a great hall of an office and presented with a contract. Sign here! And just as quickly, when the youngster failed to make the red Italian 500cc two-strokes crush the major factories, he was discarded. That was his first big lesson on life at the top: It’s precarious.

In 1996, Mladin signed to ride Yoshimura Suzukis in the U.S. Those were dark days for Suzuki, which had become so demoralized in the 1990s that the team had started to park its transporter away from the others, as if its lack of results might be contagious. Valves broke. Tires went up in smoke from an undeveloped, unrefined powerband. The team seemed to cherish the hope that some hot young gun would come forward who could “just ride” the GSX-R as it was. Newly hired riders, desperate for something positive to say, told interviewers, “The bikes really have a lot of.. .potential.”

Mladin described to me his first season: “We went to Daytona, and I smoked the tires off the bike. Then at the next race, we were fourth. And at Laguna-that’s when it used to be in April-I would’ve ended up third but Miguel Duhamel crashed chasing Doug Chandler. I got to the pits and learned that I was second, 20 seconds back. That’s three-quarters of a second a lap (in racing, that’s a lifetime). I got the most pats on the back that day; it was as if we’d won the galactic championship. I thought, ‘What’s going on?’ That was the mentality they had-they were glad to finish second.

“In 1997, I went to Ducati because I was still thinking in terms of Europe, and that seemed to offer a better window. In the meantime, I found I enjoyed living in America. So, in ’98, I was back at Suzuki. I told them I needed big changes: These are the people I want, these are the changes I need. Reg O'Rourke was with me from the beginning, but then we got Ammar Bazzaz, and later, Peter Doyle. And the results began to come. It took several years to build up to what we eventually had.”

I had seen it happen before: the classic situation in which a skeptical factory, after previous disappointments, learns by degrees that this rider can transform the changes he’s asking for into success. It happened with Kenny Roberts; slowly, because Yamaha at the time was dazzled by dashing Latins-Giacomo Agostini and Johnny Cecotto. But Roberts made things happen, so he began to get the parts. Mladin made things happen for Yoshimura and Suzuki. Everyone got an education in the process. Ammar Bazzaz was in climate science back East and, just for fun, answered a Yoshimura want ad for a computer tech. They interviewed and hired him. When he got the hang of their data system, he used it to make clear to Mladin all the gains he could have by the right setup changes almost “for free.” This meant he could go significantly quicker than his rivals at less cost or risk to himself. No more “just ride harder.” The changes worked like compound interest-the result was more than the sum of the parts. Peter Doyle arrived and his insights unlocked further areas.

I asked Mladin how different this past season’s AMA American Superbike was from past Suzukis, which were “real” Superbikes.

“My old Superbikes felt a lot more racebike-like,” he replied. “The new bike was soft, and I couldn’t pull the brakes like I wanted. The horsepower wasn’t that far off. The stiffness wasn’t that far off. But it reminded me of production bikes. On a real Superbike, there is lap time in pushing the bike harder and harder and harder.

“My contract was up this year, but with the kind of decisions and changes being made in racing-and the reasoning for putting up with them-I couldn’t sign a new contract and go back to that. It would have been hypocritical.”

Racing is not just a job. A mortal human needs strong, hot reasons for choosing it over real estate or plumbing. Yes, the money was good (Mladin has said all along, “I’m the second-bestpaid rider in the world”), but the real attraction was the fast and fascinating multi-level game in which much could be won and everything was at stake. He wanted to play-every race, every corner. When he started at Suzuki, the team was down. He and his crew picked up the pieces and, while jointly improving them, Mladin rode the best they could build on the day as hard as it would go. Up they went by their collective bootstraps. No one knows the details, but it is said his contract provided bonus money only for wins. Whatever the terms, we know he pushed out big stacks of chips on every bet.

Any other factory had the physical resources to do the same in AMA Superbike, especially during Mladin’s early years. Suzuki is only number three in the Japanese pecking order. But in the other teams, nothing like the “Mladin process” took root and grew. In the end, only Suzuki had a full-spectrum race team, and it showed in the results.

In 2009, with much closer-to-production American Superbike equipment rules, Mladin came back and won a seventh title. Of all the chatter this year about races won or lost, he said, “The people who talk the most generally have the smallest results. Bottom line is, there are those who know and those who think they know. Results speak for themselves.”

Now, off Mladin goes to a new life in Australia, a life in which family will be a greater part. He has a variety of business interests, and his love of flying to occupy the rest of his time. It was a great ride.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontFrom One Enthusiast To Another

JANUARY 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

Best Bargain:

Best Bargain:Honda Interceptor

JANUARY 2010 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

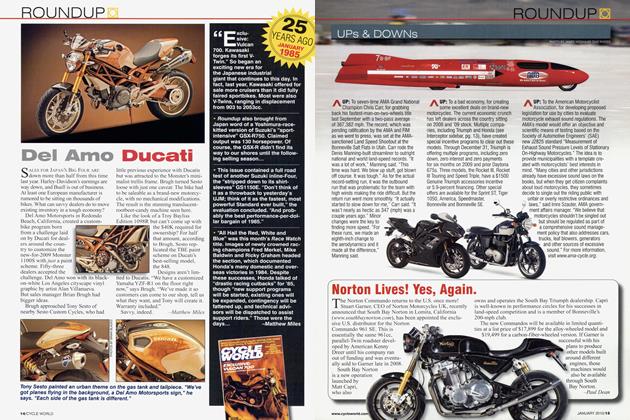

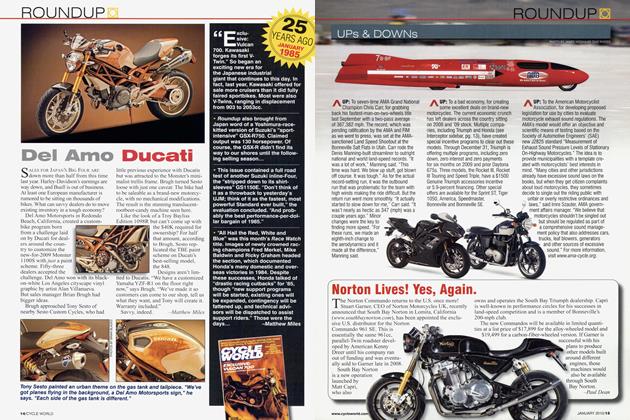

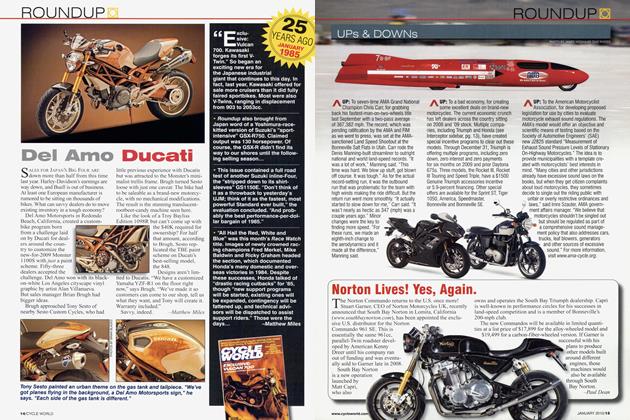

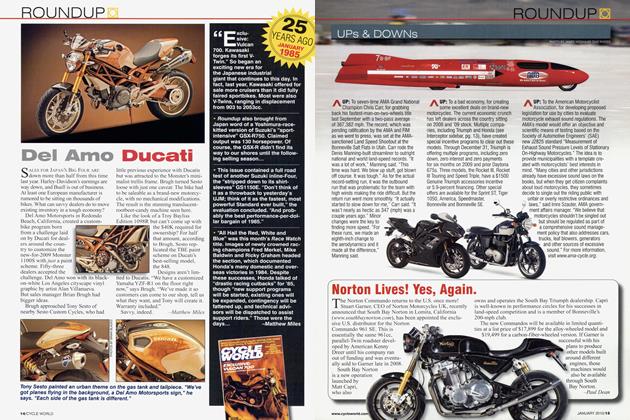

RoundupDel Amo Ducati

JANUARY 2010 By Matthew Miles -

25 Years Ago

JANUARY 2010 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupUps & Downs

JANUARY 2010 -

Roundup

RoundupNorton Lives! Yes, Again.

JANUARY 2010 By Paul Dean