HAP ALZINA & THE ILL-FATED ARROW

RACE WATCH

A true story of a day and place where winning wasn't everything

ALLAN GIRDLER

HAP ALZINA LOVED MOTORCYCLING. There was no doubt whatsoever about that. Born in 1894, at the dawn of the sport, Alzina got his first motorcycle when he was barely in his teens and went to work as a mechanic as soon as he turned 16. He raced dirt-track and hillclimbs and endurance runs, in which he was good enough to defeat the legendary Cannonball Baker at least once.

Alzina was also an effective and austere man of business. The mechanic’s job became service manager, then he bought an agency that was doing poorly and put it into the black so quickly that indian-at the time the world’s largest motorcycle-maker-made him district, then California and later West Coast distributor of the brand.

Through no fault of Alzina, Indian declined. Founders George Hendee and Oscar Hedstrom had retired and the company was taken over by men who knew finance but not motorcycles. On at least one occasion, Alzina crossed the country with a suitcase packed with cash so the factory could meet the payroll.

That isn’t to say Alzina didn’t enjoy himself. His dealership was in Oakland, California, and nearby was Mount Tamalpais, topped with a pagoda and accessed via a railroad. In 1915, he rode his Indian up the tracks and with some help from friends boosted it atop the pagoda’s railing, all to get his favored brand of tire into the newspapers.

And-this is one of the keys to the story-Hap Alzina was a family man. As one would guess from the smile in photos, wife Lil was a charming woman. They had three children-two strapping sons and a pert and perky daughter.

Here we pause the disc and select a different scene: It’s the depth of the worldwide Depression. Indian is using two percent of the plant’s capacity, and Alzina is shipping parts back east so the company can fill what few orders it has.

Indian management has improved. The new majority stockholder is Paul DuPont, yes of the DuPont paint and chemical empire, another man of business and a motorcycle fan since his teen years.

Indian Motocycle-not only did Hendee spell it that way, Indian had a patent on the word-was one of the two surviving American motorcycle makers. Harley-Davidson was also running in the red but had enough cash to engineer and produce a new and sporting middleweight: the evergreen Model E, a 61-cubic-inch overhead-valve Twin.

In 1937, Harley’s racing department went to Daytona Beach to set some records and gain some publicity. They had stock bikes-well, mostly stock-for the 45and 74-inch classes. But the main contender was a Model E, fitted with magneto and two carburetors, and streamlined by the addition of spats over the wheels, trailing covers for the fork tubes, a tiny fairing for the rider to >

crouch behind and full enclosure for the rear of the machine. With Joe Petrali doing the riding, the machine’s official time, a two-way average, was 136.183 mph.

The good news was that this was an American speed record and gave Harley-Davidson the hoped-for publicity, in that it took the record from earlier Indian runs and that the record made that Model E the fastest non-supercharged motorcycle in history.

The bad news was that the actual speed runs had been made with the bodywork removed. The bike had simply been too unstable as originally run. The embarrassing news-and probably the worst-kept secret in racing-was that the press photos and release never exactly admitted that the motorcycle was shown wearing the bodywork it hadn’t actually used. There were no lies but, as someone says in the movies, the PR staff did have a talent for fiction.

Hap Alzina saw this as a challenge and an opportunity.

Pause the DVD again and find scenes from the 1920s. National motorcycle racing then was mostly what was known as Class A: full-race engines and special frames allowed, choice of fuel and a vague suggestion that the equipment be offered to the sporting public, which it never really was.

Excelsior, at the time the third American maker, created a 750cc class when it released the Super X, an intake-over-exhaust V-Twin, later replaced with a full overhead-valve version. The Super X did so well that both Harley and Indian countered with 750 Class A engines.

Road machines of the time were ioe or sidevalve, cheaper and quieter and easier to service. Because the fuel was low octane, higher compression ratios weren’t practical. But this didn’t mean the guys in the race shops didn’t know how to make engines that performed. The Class A 750s were built with compression ratios up to 15:1, ran on alcohol blended with benzol and made good power. There used to be a quip that a real racing engine was one next to which it wasn’t comfortable to stand, and on one occasion this reporter was there when one of these antiques was fired up. We all stepped back.

Indian, meanwhile, had put its dwindling eggs in the wrong basket by developing and promoting its inlineFour-the top of the line but never as popular as the sales force had hoped and way beyond the sporting rider’s budget or even his ambitions.

While Class A racing had declined, those ohv V-Twins were still in service. Alzina owned one; historian Harry Sucher says there’s some evidence it was the actual engine used by Johnny Seymour to set the American record132 mph-that Petrali broke, and it had been bored and stroked to 1 OOOcc or 61 cubic inches.

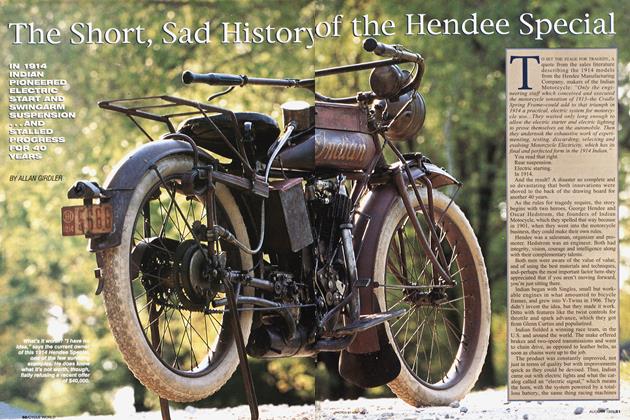

Shades of Burt Munro, Alzina and his ace mechanics pieced together parts from the 101 Scout and earlier bits, tuned the engine as far as they dared and installed it as low in the frame as they could, ground clearance not being a concern.

Harley’s problems with the streamlining were public knowledge, so Alzina and backers called in an aerodynamicist, one with motorcycling experience.

He designed a shell, like a lima bean on edge, which fully enclosed the bike proper. It came in two halves-front and back. Rider Fred Ludlow, who had already set many speed records for Indian, climbed aboard with the front half in place and then the rear half was attached. The shell was literally built as close to Ludlow, who was not a big man, as it could be. A set of tiny wheels, retracted at speed, was the only part of the ’liner extending past the shell.

In 1937, the team went to test at Muroc dry lake, scene of too many record runs to list. Everything looked as good as one could hope. Seymour, Alzina’s oldest son, had ridden that engine, in a bare frame, to 132 mph. Ludlow had been clocked on a Class C Scout at 128 mph. Since the target was any speed higher than 137, no worries, eh?

Pause again and select a different scene. It’s a sad truth, universally acknowledged, that the worst thing that can happen to any human being is to lose a child. Nothing can be more painful or less fair.

Seymour was a natural athlete and budding scholar, a young man of promise and, of course, the apple of his parents’ eyes. He and a buddy were hunting ducks, there was an accident and the pal was hurt. Young Alzina went for help. Either he overestimated his strength or discounted the difficulty, but either way, he drowned. Keep that in mind as we return to Muroc for testing.

They began slowly, as was proper, and ran 100 mph with no problems. They upped the speed and, darn, the engine threw a rod! They went back to the shop, and the engine was fixed easily enough. But because the summer and heat were approaching, and because there were rumors (later made fact) that Muroc was to become Edwards Air Force Base, they decided to wait for cooler weather and move the attempt to Bonneville’s salt flats.

The crew arrived at Bonneville on schedule in September of 1938. Everything looked good, so they fired the engine and off Ludlow went. At an indicated 135 mph, the streamliner began to wobble. A check showed nothing

out of the ordinary. This time, at 145 indicated, the wobble became a tank-slapper, ripping the grips from Ludlow's hands.

Back up a year. When the Harley record-setter didn't work as built, the crew removed the bodywork and Petrali tucked in, held on and set the record. He was a tough man. And he’d never lost a child.

The Indian crew considered all the options. It could have been that the front suspension and alignment simply weren’t right for the speed and so forth. Or maybe the streamlined shell was at fault. Either way, Alzina simply said under no circumstances would he risk anyone’s life just to set a record or promote a brand. The ’liner was parked, never to run for serious again.

Does the story end there? No. Ludlow climbed onto the tuned 45-inch Sport Scout and set a Class C record for 750s: 115.126 mph. He climbed onto the Chief and set a Class C record for 1200s: 120.727 mph. Both times beat the earlier records held by HarleyDavidson. (The official certification records show the runs were made using > high-test gas, rated at 76 octane, one reason the sidevalve engines were useful for so many years.)

In other news, Miss Alzina married a motojournalist and lived happily ever after; motojournalists are Prince Charmings, every one. The younger Alzina son went racing and did well, especially in hillclimbs, just like dad.

Alzina himself saw the handwriting on the wall. In 1949, he resigned the Indian distributorship and took on the BSA brand on the West Coast. He sponsored more top racers than can be listed here, and he persuaded BSA’s manager to design and homologate the machines that kept BSA in AMA contention until the very end. Alzina died in 1960 and was one of the first men named to the Motorcycle Hall of Fame.

Another brand went after the speed record using a lima bean shell very like that of the Arrow. At speed, that ’liner, too, went out of control and slid to a stop on its side. No one was hurt, but by that time, science had worked out that lima beans are too short for high speeds, which is why Munro, Johnny Allen and Cal Rayborn set their records with torpedo-shaped bodywork, and why dirt-tracker Chris Carr rode inside a body shaped like a salmon. Then we invented nostalgia, and the Arrow was dragged out of the shed and became a feature in shows and displays.

All for good, surely. But one can’t help wonder what would the speed have been if Ludlow had run the Arrow minus the shell. And if the suits at Indian way back when had named Hap Alzina president, would there right this minute be Sport Scouts for sale at an Indian store near us? □

For more photos of the Indian Arrow, go to www.cycleworld.com.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Lost Von Dutch

September 2009 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThis Is Your Brain On Motorcycles

September 2009 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCOld World Craftsman

September 2009 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2009 -

Roundup

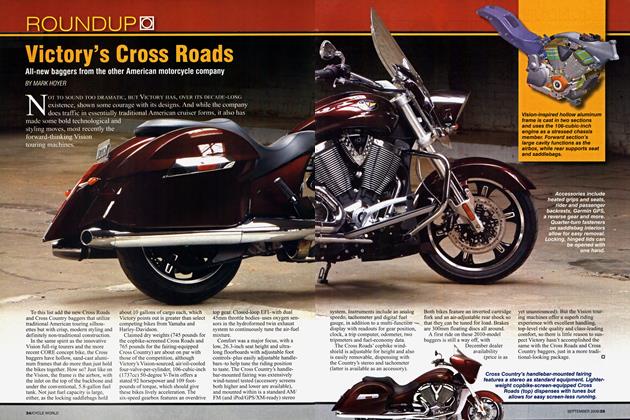

RoundupVictory's Cross Roads

September 2009 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago September 1984

September 2009 By Blake Conner