Old World Craftsman

TDC

Kevin Cameron

I HAVE BEEN THINKING ABOUT THE SPLIT between large Chinese motorcycle manufacturer Haojue and former Aprilia racing manager Jan Witteveen. Witteveen and engine-development engineer Franco Moro (ex-Aprilia, ex-Fantic) were contracted to design for Haojue a 125cc two-stroke Single for Grand Prix roadracing-something surely straightforward if not actually easy, given their background.

The split came when the resulting Haojue (formerly Maxtra) 125 proved unreliable and was down 10 mph in top speed from the competition, implying a 20 percent power deficit. The design provided to Haojue (and manufactured largely in Italy, as you’d expect, by the usual providers of critical parts for European racing projects) was a bit unusual in a couple of ways. First, instead of employing rotary-valve inlet as the Aprilia 125 and 250 do, the designer!s) gave it a forward-facing reed-inlet system more like that of the unsuccessful Fantic 250 V-Twin racer. And second, the engine’s cylinder pointed down and forward, recalling Kawasaki’s X-09 250 of 1992.

Why would Witteveen have given Haojue a lesser design than the best available to him-one based upon the successful Aprilia rotary-valve 125? Was he legally compelled to do so by a non-compete agreement, signed at the time of his departure from Aprilia? Or was his managerial position at Aprilia remote from actual design details? We may never know for sure.

Where do successful racing motorcycle designs come from? The big companies like to imply that they design motorcycles by feeding requirements into the usual “giant electronic brain,” which then spews forth a solution. The uncomprehending humans manufacture this and-Kfr/ö/-excellence is born. But in fact until very recently, actually getting the power from a newly drawn two-stroke cylinder has been the province of experience and craftsmanship. Today, too many people have seen Aprilia, Honda and KTM cylinders for there to be any secrets. And there will be little more development, as the 250 GP class becomes a 600cc four-stroke spec-engine class next year.

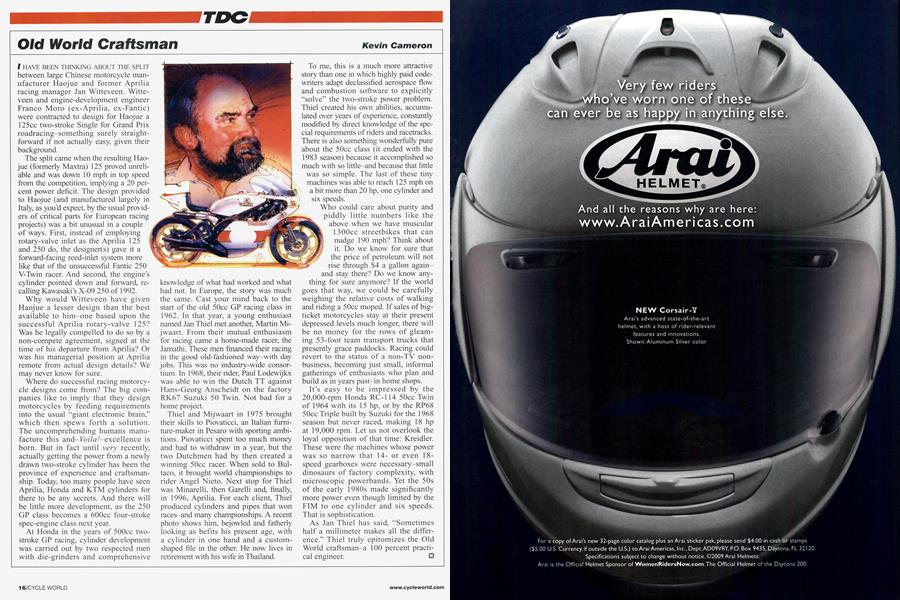

At Honda in the years of 500cc twostroke GP racing, cylinder development was carried out by two respected men with die-grinders and comprehensive knowledge of what had worked and what had not. In Europe, the story was much the same. Cast your mind back to the start of the old 50cc GP racing class in 1962. In that year, a young enthusiast named Jan Thiel met another, Martin Mijwaart. From their mutual enthusiasm for racing came a home-made racer, the Jamathi. These men financed their racing in the good old-fashioned way-with day jobs. This was no industry-wide consortium. In 1968, their rider, Paul Lodewijkx was able to win the Dutch TT against Hans-Georg Anscheidt on the factory RK67 Suzuki 50 Twin. Not bad for a home project.

Thiel and Mijwaart in 1975 brought their skills to Piovaticci, an Italian furniture-maker in Pesaro with sporting ambitions. Piovaticci spent too much money and had to withdraw in a year, but the two Dutchmen had by then created a winning 50cc racer. When sold to Bultaco, it brought world championships to rider Angel Nieto. Next stop for Thiel was Minarelli, then Garelli and, finally, in 1996, Aprilia. For each client, Thiel produced cylinders and pipes that won races-and many championships. A recent photo shows him, bejowled and fatherly looking as befits his present age, with a cylinder in one hand and a customshaped file in the other. He now lives in retirement with his wife in Thailand.

To me, this is a much more attractive story than one in which highly paid codewriters adapt declassified aerospace flow and combustion software to explicitly “solve” the two-stroke power problem. Thiel created his own abilities, accumulated over years of experience, constantly modified by direct knowledge of the special requirements of riders and racetracks. There is also something wonderfully pure about the 50cc class (it ended with the 1983 season) because it accomplished so much with so little-and because that little was so simple. The last of these tiny machines was able to reach 125 mph on a bit more than 20 hp, one cylinder and six speeds.

- Who could care about purity and piddly little numbers like the above when we have muscular 1300cc streetbikes that can • nudge 190 mph? Think about J it. Do we know for sure that the pnce of petroleum will not - rise through $4 a gallon againand stay there? Do we know any thing for sure anymore? If the world goes that way, we could be carefully weighing the relative costs of walking and riding a 50cc moped. If sales of bigticket motorcycles stay at their present depressed levels much longer, there will be no money for the rows of gleam ing 53-foot team transport trucks that presently grace paddocks. Racing could revert to the status of a non-TV non business, becoming just small, informal gatherings of enthusiasts who plan and build as in years past-in home shops.

It’s easy to be impressed by the 20,000-rpm Honda RC-114 50cc Twin of 1964 with its 15 hp, or by the RP68 50cc Triple built by Suzuki for the 1968 season but never raced, making 18 hp at 19,000 rpm. Let us not overlook the loyal opposition of that time: Kreidler. These were the machines whose power was so narrow that 14or even 18speed gearboxes were necessary-small dinosaurs of factory complexity, with microscopic powerbands. Yet the 50s of the early 1980s made significantly more power even though limited by the FIM to one cylinder and six speeds. That is sophistication.

As Jan Thiel has said, “Sometimes half a millimeter makes all the difference.” Thiel truly epitomizes the Old World craftsman-a 100 percent practical engineer. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

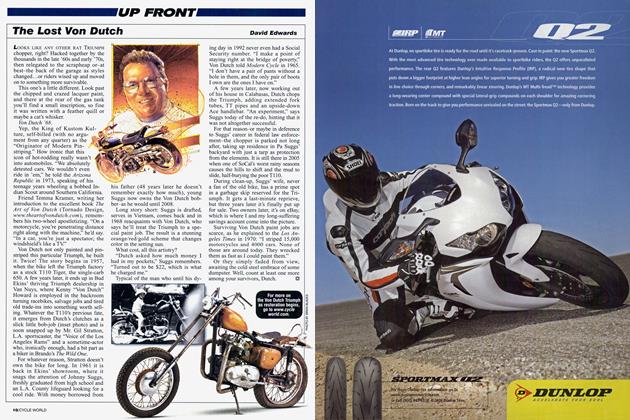

Up FrontThe Lost Von Dutch

September 2009 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThis Is Your Brain On Motorcycles

September 2009 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2009 -

Roundup

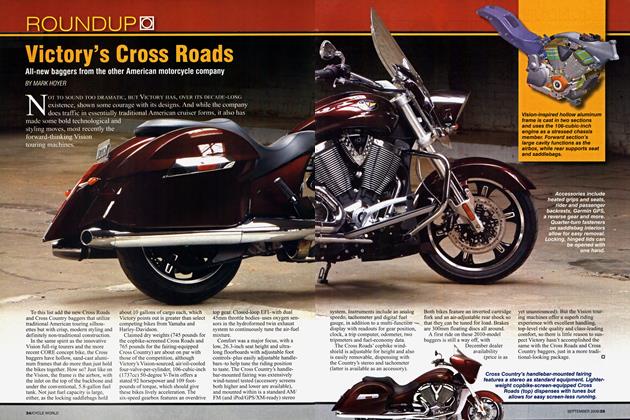

RoundupVictory's Cross Roads

September 2009 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago September 1984

September 2009 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupFuzzy Spy Shots!

September 2009 By Blake Conner