Original Ninja

Fast times at Laguna Seca

JOHN ULRICH

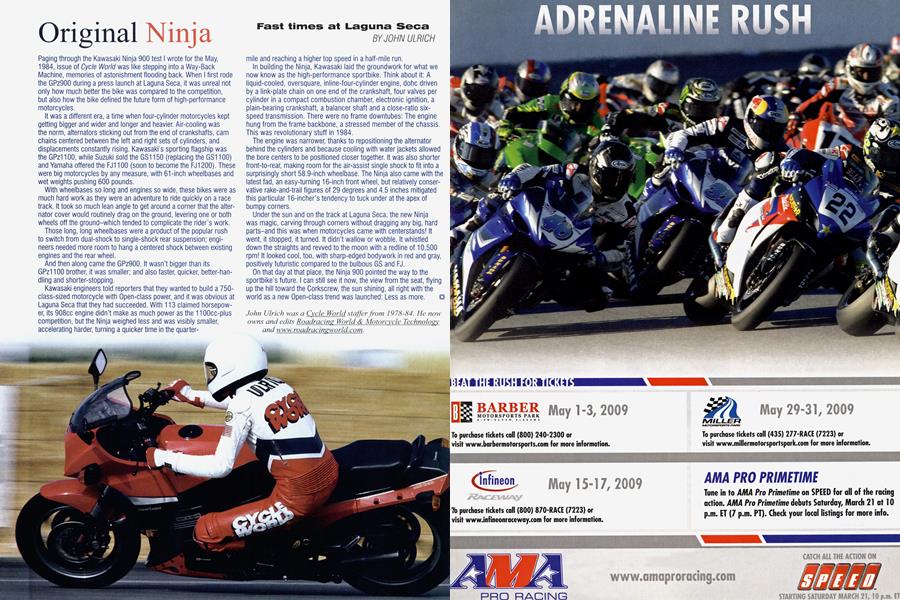

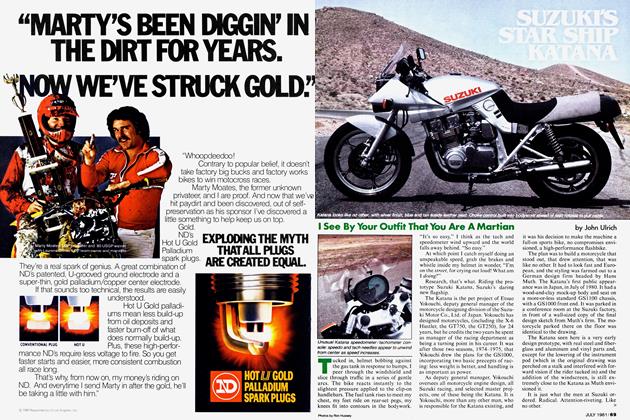

Paging through the Kawasaki Ninja 900 test I wrote for the May,

1984, issue of Cycle World was like stepping into a Way-Back Machine, memories of astonishment flooding back. When I first rode the GPz900 during a press launch at Laguna Seca, it was unreal not only how much better the bike was compared to the competition, but also how the bike defined the future form of high-performance motorcycles.

It was a different era, a time when four-cylinder motorcycles kept getting bigger and wider and longer and heavier. Air-cooling was the norm, alternators sticking out from the end of crankshafts, cam chains centered between the left and right sets of cylinders, and displacements constantly rising. Kawasaki’s sporting flagship was the GPz1100, while Suzuki sold the GS1150 (replacing the GS1100) and Yamaha offered the FJ1100 (soon to become the FJ1200). These were big motorcycles by any measure, with 61-inch wheelbases and wet weights pushing 600 pounds.

With wheelbases so long and engines so wide, these bikes were as much hard work as they were an adventure to ride quickly on a race track. It took so much lean angle to get around a corner that the alternator cover would routinely drag on the ground, levering one or both wheels off the ground-which tended to complicate the rider’s work.

Those long, long wheelbases were a product of the popular rush to switch from dual-shock to single-shock rear suspension; engineers needed more room to hang a centered shock between existing engines and the rear wheel.

And then along came the GPz900. It wasn’t bigger than its GPz1100 brother, it was smaller; and also faster, quicker, better-handling and shorter-stopping.

Kawasaki engineers told reporters that they wanted to build a 750class-sized motorcycle with Open-class power, and it was obvious at Laguna Seca that they had succeeded. With 113 claimed horsepower, its 908cc engine didn’t make as much power as the 1100cc-plus competition, but the Ninja weighed less and was visibly smaller, accelerating harder, turning a quicker time in the quarter-

mile and reaching a higher top speed in a half-mile run.

In building the Ninja, Kawasaki laid the groundwork for what we now know as the high-performance sportbike. Think about it: A liquid-cooled, oversquare, inline-four-cylinder engine, dohc driven by a link-plate chain on one end of the crankshaft, four valves per cylinder in a compact combustion chamber, electronic ignition, a plain-bearing crankshaft, a balancer shaft and a close-ratio sixspeed transmission. There were no frame downtubes: The engine hung from the frame backbone, a stressed member of the chassis. This was revolutionary stuff in 1984.

The engine was narrower, thanks to repositioning the alternator behind the cylinders and because cooling with water jackets allowed the bore centers to be positioned closer together. It was also shorter front-to-rear, making room for the air-assist single shock to fit into a surprisingly short 58.9-inch wheelbase. The Ninja also came with the latest fad, an easy-turning 16-inch front wheel, but relatively conservative rake-and-trail figures of 29 degrees and 4.5 inches mitigated this particular 16-incher’s tendency to tuck under at the apex of bumpy corners.

Under the sun and on the track at Laguna Seca, the new Ninja was magic, carving through corners without dragging any big, hard parts-and this was when motorcycles came with centerstands! It went, it stopped, it turned. It didn’t wallow or wobble. It whistled down the straights and revved to the moon with a redline of 10,500 rpm! It looked cool, too, with sharp-edged bodywork in red and gray, positively futuristic compared to the bulbous GS and FJ.

On that day at that place, the Ninja 900 pointed the way to the sportbike’s future. I can still see it now, the view from the seat, flying up the hill toward the Corkscrew, the sun shining, all right with the world as a new Open-class trend was launched: Less as more. □