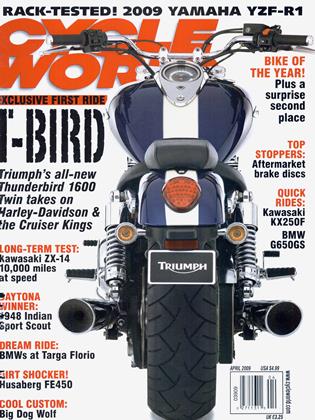

THUNDER ROAD

CW EXCLUSIVE

TRADITION AND INDIVIDUALISM RUMBLE AT THE core of the cruiser market. The first point is what drives the proliferation of V-Twins in the segment, but the second makes this very proliferation somewhat ironic.

Triumph had a different idea and knew full well that to ignore its own tradition of Twinness-the parallel kindmight be interpreted as too “me-too” and inauthentic for the British company. So a Vee was out.

Riding Triumph's all-new big-bore cruiser Twin

MARK HOYER

Meet the 2010 Thunderbird, its 1596cc parallel-Twin giving this classic American-style bike a British heart, albeit a rather enlarged one!

Cycle World got an early first ride on a pre-production Thunderbird to gather some initial impressions long before the expected summer-2009 on-sale date. My ride was but a half-day in the Spanish mountains outside Barcelona near the IDIADA multi-brand (two and four wheels) proving grounds and testing facility. IDIADA is an acronym for a very long Spanish phrase that I believe translates to “A place to ride motorbikes when it is waaaay too effin’ cold in jolly olde England...” Okay, maybe not, but there is plenty going on inside the secure walls (the never-ending howling tires of a car on a skidpad, for example), which is why we weren’t allowed to enter!

The bike was shuttled out by Triumph’s lead tester, David (say Dah-VEED) Lopez. The 30-something Spaniard exroadracer, who is also a trained mechanical engineer, has been making Triumphs handle sweetly since the turn of the century, playing a role in most every machine since the TT600. Also on hand was Triumph Product Manager Simon Warburton, in charge of the types of bikes Triumph makes.

“David just can’t make a badhandling bike,” said Warburton in a hushed tone so none of the other manufacturers at the facility might hear him.. .then added, “David is a very valuable member of our chassis team, but I need to add the proviso that I’m sure David would add: He works as part of a team. There are two dozen engineers and technicians involved in the Thunderbird project, and the bike is the result of the work of all of them.”

In any case, Cycle World agrees about the development team’s ability to make Triumphs handle. I went back through the years reading about key machines that Lopez & Co. had helped develop, and we have almost always praised their superb handling, even when we were hard on the bikes in other areas.

Obviously, a cruiser like this has a different emphasis than, say, the Daytona 675, but you still need to find the happy numbers. Warburton comments on the process: “We know that cruisers are not famed for their dynamic capabilities, and we know that there are certain characteristics of this type of bike that mean there will always be limitations (such as cornering clearance), but we wanted the Thunderbird to feel like a Triumph, which means it had to be comfortable, easy and confidence-inspiring around corners as well as on the straights.”

I got a good inkling of this back when I rode the early prototype

Thunderbird in England during December, 2007. So when I threw a leg over this near-production version, I was already familiar with the bike’s ergonomic package, which had been set way back then. As I settled into the 27.5-inch-high (and generously wide) saddle, I was pleased to find the same “cruiser rational” riding position. Despite the feet-forward/sweptbackbar stance, the general character is fairly upright and therefore quite comfortable.

Suspension tune is compliant, but with a surprising degree of well-controlled damping for a cruiser. The fork is a very large 47mm conventional Showa unit with no adjustments. The twin shocks are also from Showa and have provision for springpreload adjustment. A 32-degree rake and long, 64.6-inch wheelbase keep steering on the relaxed side, but hustling down winding roads doesn’t unsettle the bike. The only real limitation on a winding road-as is the norm in the cruiser class-is cornering clearance, but the Thunderbird leans adequately for its intended purpose. Braking performance is strong from the triple 310mm-disc setup, which shrugs off hard stops with a medium-effort pull on the lever. The rear brake, however, is a bit numb in terms of feedback. ABS will be an option, but our bike was standard.

Ridden at a typical cruiser pace where you are interacting more with the scenery while letting the nuances of the tarmac and where precisely to apex fall farther to the back of your mind, the nicely weighted steering (with mild inside bar pres-

sure holding your cornering line) is a pleasure. Low-speed U-turns are also easy to execute. The handling truly belies the bike’s expected (but not finalized) 680-pound dry weight.

A large part of this cornering character comes from

the specially constructed, T-Bird-specific 120/70ZR19 and 200/50ZR17 Metzeler ME880 tires. The latter is significant in the sense that it is not any larger. “The Thunderbird’s tires certainly contribute to the way it handles-tires are vital parts of any bike’s chassis setup,” said Warburton. “We chose the 200 section because it looked right on the bike, and we were confident that this size of tire would give us the chassis attributes we wanted. We didn’t try out any bigger-section tires.” The implication in the last statement is that the chassis attributes were of larger importance than going “size-matters” and compromising ride quality. The resulting bike is indeed nice-handling and comfortable to ride.

"Suspension tune is compliant, but with a surprising degree of well controlled damp ing for a cruiser."

But the news here is in the engine room. Cylinder dimensions for this all-new counterbalanced dohc Twin are an impressive 103.8 x 94.3mm bore and stroke. Output goals were 80 horsepower and 100 foot-pounds of torque, which the company says it exceeded, although official numbers await final emissions homologation.

On the road, this is a good-running motor, with loads of bottom-end torque and pleasing sound from the exhaust-the 270-degree crankshaft spaces the firing in a way that mimics a V-Twin sound. This was a specific move on Triumph’s

part to satisfy the aural expectations of a mainstream cruiser buyer, because there is no doubt who Triumph is after here. Traditionalists with old Meriden 360-degree bikes in their garages might like the more-even drone of the old crank layout, but the 270 meets sonic expectations for a bike with the Thunderbird’s silhouette.

And it does sound good.

Fuel mapping for the EFI system is excellent and there is lots of flywheel inertia for the kind of luggability we’ve come to expect from a large Twin. Rev it anywhere near its 6500-rpm redline and there is plenty of boogie, too. The real sweet spot is between 1800 and 3500 rpm. The engine is alive with torque in this range, and the bike lunges forward with significant and immediate snap.

Even spun up pretty high in revs, the engine has no unpleasant vibes (thanks to the counterbalancing), just whacking great big power pulses that inform you there is real combustion going on in that pair of 798cc-apiece cylinders.

The early prototype I rode for our exclusive technical preview (“T-Bird,” November, 2008) had a lot of this character and sizzle when revved up, but it was unrefined at lower revs. The smoothing solution to the bottom-end power during ensuing development was to add a big lump of inertia-some 20 pounds !—to the crank. It worked. With a bit of restraint on the throttle, this engine can be dropped nearly to the 800-rpm idle speed in most gears and pull away cleanly.

I “Between 1800! 3500 rpm, the ! engine is alive I with torque; I the bike lunges j forward with ¡ significant snap.”

From about 1400 revs, even with the transmission in overdrive sixth gear, roll on the gas with impunity. You just go.

In terms of refinement and pleasant mechanical sounds, the Thunderbird’s 1600cc mill is more than competitive

with American and Japanese offerings in its class. Not even the starter motor makes unpleasant or out-of-the-ordinary noises.

Feel from the cable-actuated clutch is quite good, and the pull at the lever is surprisingly light. Shift quality from the new gearbox-using quieter, helically cut gears in second through sixth-is also good, although it falls a little short of the sort of satisfying mechanical operation of current Harley-Davidson Big Twin gearboxes. But the Triumph transmission is transparent and quiet in its function. Belt final drive suits the cruiser norm and makes custom wheels a more accessible accessory than they would be with shaft drive.

The $12,999 base price (the ABS version is $800 more) puts the Thunderbird right on par with its Japanese competition and makes the bike cheaper than most offerings from Victory and Harley-Davidson.

The Triumph’s non-traditional engine layout surely will appeal to riders looking for just a bit more individualism in what is otherwise a very traditional-looking cruiser.

And, hey, if you feel the engine is a little too different for your taste, just think of it as a 0-degree V-Twin! You won’t be disappointed. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBike of the Year

April 2009 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Captive Enfield

April 2009 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCBreakage

April 2009 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2009 -

Roundup

RoundupCall of the Wild

April 2009 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupCustoms Live: Reports of Hot-Rodding's Demise Have Been Greatly Exaggerated

April 2009 By Paul Dean