No Limits?

Maddison does the math

KEVIN CAMERON

WATCH THE VIDEO. AUSTRALIAN Robbie Maddison accelerates his Yamaha YZ250 down a short ramp and runway to gain speed, then transitions to a second, nearly vertical ramp. He shoots up, off the end, noses the bike over and lands easily atop the 96-foot-high replica Arc de Triomphe in Las Vegas. Ten stories up. We gasp.

He makes a slow lap of the roof, then stops to look down at the descent ramp. Another couple of slow laps and he simply rides off the edge into space. An extra foot per second or two carry him farther out than planned, so he falls almost to the transition before hitting very hard. But he recovers and a moment later brakes to a stop.

It looked like a crazy stunt, but it was clear there was science behind it. I phoned to talk with Maddison, who explained that in this business, “You have to come up with a fresh concept-thinking outside the square.”

His first goal, completed a year earlier, was to jump farther, not higher. He sold his

distance jump as “jumping a football field,” and it worked-Red Bull funded the program. But what tops a 322-foot jump?

“I’m driving down the freeway, looking at all these buildings, and I’m thinking about this,” he said. “I’m counting floors. And that’s how the (vertical jump) idea came to me. Five? That’s not enough. Ten stories seemed about right.”

He took on a physics advisor, Eric Brooking. Brooking told me, “Initially, Robbie was able to do a lot of things by seat-of-the-pants feel and sheer experience. Jumpers distrusted physics because it gave the wrong answers. But when you start to take account of the energy losses-air drag, suspension compression, tire friction and the flexing of the ramp-it becomes very accurate.”

To put in the right energy to accomplish the jump, speed had to be exactly controlled. Checking against a speed gun, Maddison found he could “hear” the speed in the engine sound. In run after run, he hit the required speeds by ear.

When the bike hit the ramp transition upward, it pulled many gs, and Maddison said it took all his strength to hold himself forward. The transition compressed the suspension deeply, and too-rapid of a rebound could have pushed the bike right off the nearly 70degree ascent ramp. Yet if rebound was still occurring as the bike left the top of the ramp, it would have pitched the bike

strongly nose-down. It was also essential to consider that as rebound occurred up the ramp, the actual trajectory of the man/bike center-of-mass would be slightly more than the ramp’s angle.

“We actually did practice this jump,” Maddison admitted. “We built a platform on scaffolding and started at 50 feet and could raise it to 100.”

How does a rider learn to trust the numbers? “Are you sure, mate?” was Maddison’s question as they tackled each new height. Success is hard to argue with, and they achieved predictive accuracy. Brooking said it helped a lot that Maddison could always keep the bike pointed the way it was going. That kept its frontal area constant, making air-drag calculations easier. Supercross riders use the throttle or brake to nose the bike up or down in flight-call it “inertial pitch control.”

The jump down? “That was a little scary,” Maddison said. Just a bit of extra speed off the deck took him much farther down the descent ramp than planned. Yet he survived the heavy g load.

“I think that was pure talent,” said Brooking. The force split the thumb/ forefinger web of Maddison’s left hand.

The future? “The game I’ve created for myself is very dangerous,” Maddison admitted. Tilting the scales in his favor is the unique database that he is fast accumulating. We wish him every success.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

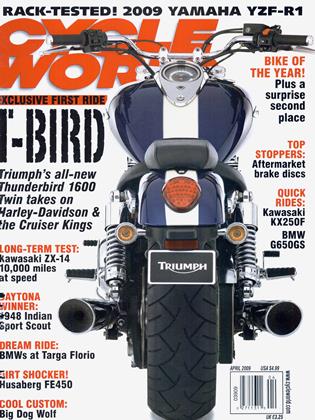

Up FrontBike of the Year

April 2009 By David Edwards -

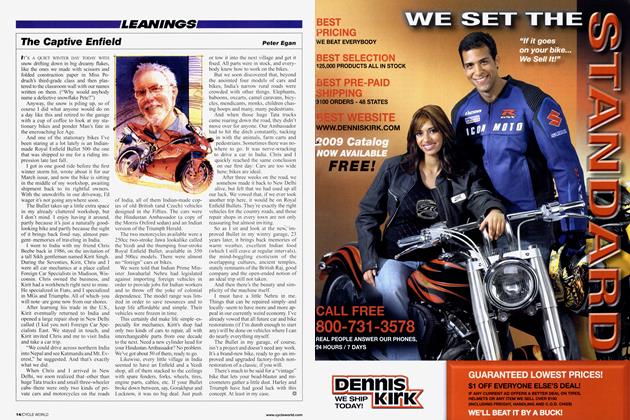

Leanings

LeaningsThe Captive Enfield

April 2009 By Peter Egan -

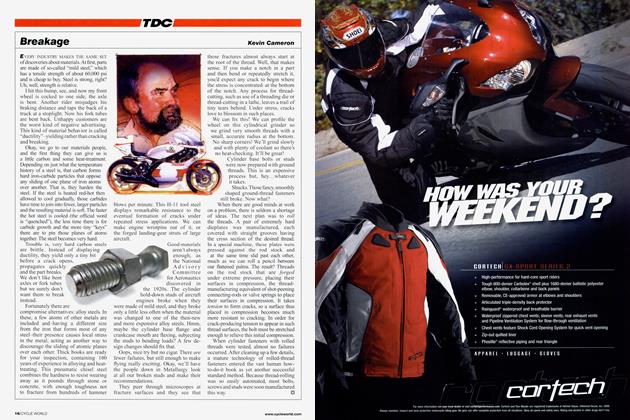

TDC

TDCBreakage

April 2009 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2009 -

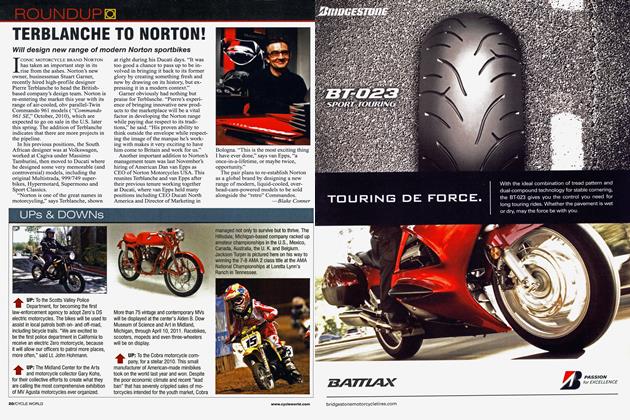

Roundup

RoundupCall of the Wild

April 2009 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupCustoms Live: Reports of Hot-Rodding's Demise Have Been Greatly Exaggerated

April 2009 By Paul Dean