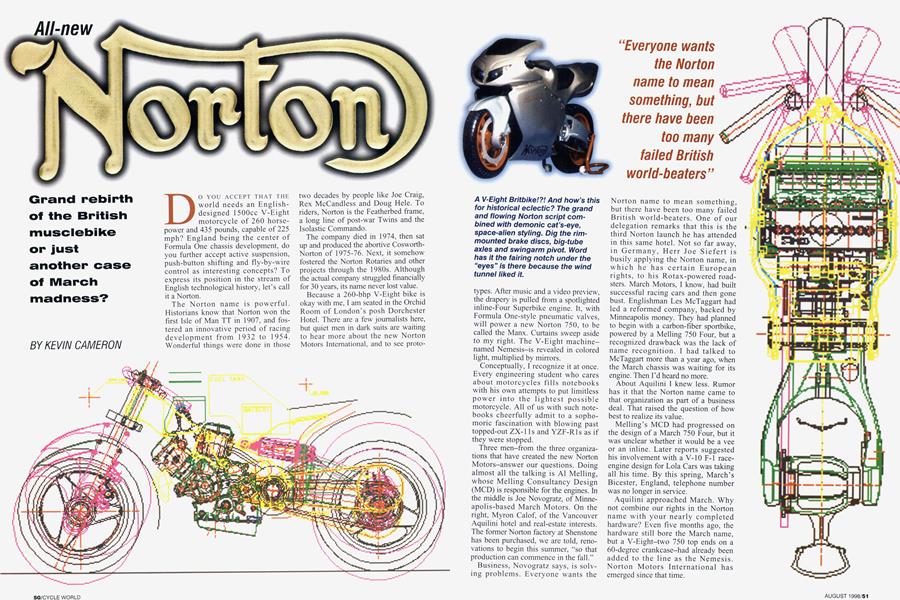

All-new Norton

Grand rebirth of the British musclebike or just another case of March madness?

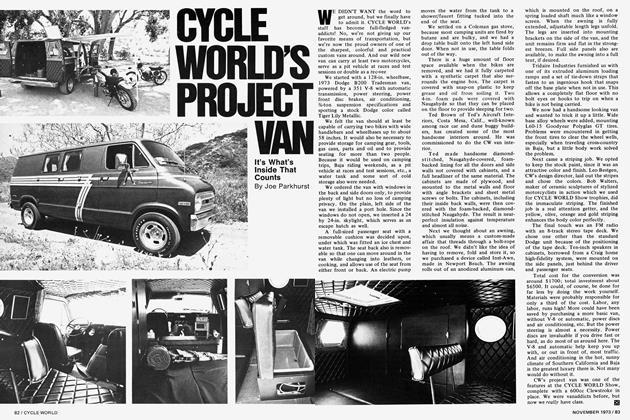

DO YOU ACCEPT THAT THE world needs an Englishdesigned 1500cc V-Eight motorcycle of 260 horsepower and 435 pounds, capable of 225 mph? England being the center of Formula One chassis development, do you further accept active suspension, push-button shifting and fly-by-wire control as interesting concepts? To express its position in the stream of English technological history, let's call it a Norton.

The Norton name is powerful. Historians know that Norton won the first Isle of Man TT in 1907, and fostered an innovative period of racing development from 1932 to 1954. Wonderful things were done in those two decades by people like Joe Craig, Rex McCandless and Doug Hele. To riders, Norton is the Featherbed frame, a long line of post-war Twins and the Isolastic Commando.

The company died in 1974, then sat up and produced the abortive CosworthNorton of 1975-76. Next, it somehow fostered the Norton Rotaries and other projects through the 1980s. Although the actual company struggled financially for 30 years, its name never lost value.

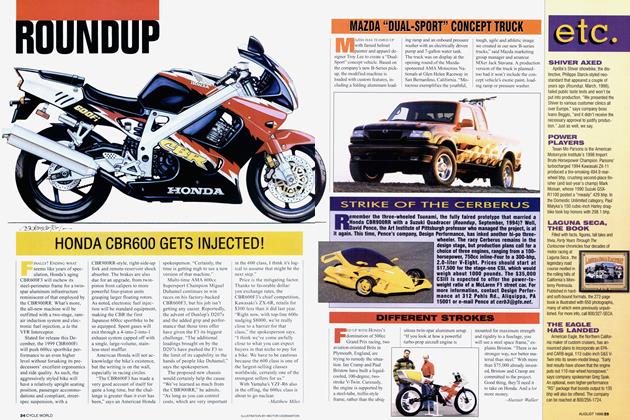

Because a 260-bhp V-Eight bike is okay with me, I am seated in the Orchid Room of London's posh Dorchester Hotel. There are a few journalists here, but quiet men in dark suits are waiting to hear more about the new Norton Motors International, and to see prototypes. After music and a video preview, the drapery is pulled from a spotlighted inline-Four Superbike engine. It, with Formula One-style pneumatic valves, will power a new Norton 750, to be called the Manx. Curtains sweep aside to my right. The V-Eight machinenamed Nemesis-is revealed in colored light, multiplied by mirrors.

KEVIN CAMERON

Conceptually, I recognize it at once. Every engineering student who cares about motorcycles fills notebooks with his own attempts to put limitless power into the lightest possible motorcycle. All of us with such notebooks cheerfully admit to a sophomoric fascination with blowing past topped-out ZX-1 Is and YZF-Rls as if they were stopped.

Three men-from the three organizations that have created the new Norton Motors-answer our questions. Doing almost all the talking is Al Meiling, whose Meiling Consultancy Design (MCD) is responsible for the engines. In the middle is Joe Novogratz, of Minneapolis-based March Motors. On the right, Myron Calof, of the Vancouver Aquilini hotel and real-estate interests. The former Norton factory at Shenstone has been purchased, we are told, renovations to begin this summer, "so that production can commence in the fall."

Business, Novogratz says, is solving problems. Everyone wants the Norton name to mean something, but there have been too many failed British world-beaters. One of our delegation remarks that this is the third Norton launch he has attended in this same hotel. Not so far away, in Germany, Herr Joe Siefert is busily applying the Norton name, in which he has certain European rights, to his Rotax-powered road sters. March Motors, I know, had built successful racing cars and then gone bust. Englishman Les McTaggart had led a reformed company, backed by Minneapolis money. They had planned to begin with a carbon-fiber sportbike, powered by a Melling 750 Four, but a recognized drawback was the lack of name recognition. I had talked to Mclaggart more than a year ago, when the March chassis was waiting for its engine. Then I'd heard no more.

About Aquilini I knew less. Rumor has it that the Norton name came to that organization as part of a business deal. That raised the question of how best to realize its value.

Melling's MCD had progressed on the design of a March 750 Four, but it was unclear whether it would be a vee or an inline. Later reports suggested his involvement with a V-10 F-l raceengine design for Lola Cars was taking all his time. By this spring, March's Bicester, England, telephone number was no longer in service.

Aquilini approached March. Why not combine our rights in the Norton name with your nearly completed hardware? Even five months ago, the hardware still bore the March name, but a V-Eight-two 750 top ends on a 60-degree crankcase-had already been added to the line as the Nemesis. Norton Motors International has emerged since that time.

"Everyone wants the Norton name to mean something, but there have been too many failed British world-beaters"

Once the short Q&A period had ended, we swarmed over the hardware and people. I was focused on Meiling and the beautifully sandcast inline-Four-there are few chances to talk about engine design with an English-speaker. Formally, the products proposed and already designed are as follows:

Nemesis-A: Cast-magnesium perimeter chassis, swingarm and wheels; F-l -style active suspension; push-button clutch and gearbox; 260-bhp, 1500cc V-Eight

Nemesis-B: Aluminum instead of mag; 235-bhp V-Eight

Manx 750 Superbike: 1) Series-produced racebike; 160-bhp; triple-sparkplug heads; pneumatic valves; 2) road version; 150 bhp; single plugs

Atlas: A 900cc Manx Commando cruiser: Pushrod 1500cc V-Eight for the U.S. market; 130 bhp; 100 ft.-lbs. of torque (Meiling adds that this will have a "cowboy saddle" and "sound like a Chevy V-Eight" because of a 90-degree crank)

of a 90-degree crank) International 600: 1) Race-replica desmo Single; 104 bhp at 11,400 rpm; for a race series planned for U.S., U.K., Australia and Japan; 2) 75-bhp roadster; 3) "65-ish-bhp" valve-spring roadster; 4) Supermotard streetbike

Ten models are a heavy program, worthy of a well-funded organization. And we, the assembled company, were firmly told that Norton Motors is financially on a "very, very secure footing." When do we see product? "Release at the end of this year," we're told. The untiring British press rumor mill assures us that the V-Eight will be priced at about $50,000.

With pneumatic valves, there are no failure-prone metal valve springs; instead, a small engine-driven pump supplies air pressure that acts beneath inverted-bucket-style tappets

Later, Meiling, other company officers and I retired to the mirror-ceilinged Terrace bar, where the broiled shrimp are large and worthy of attention. Meiling, 54, combines a comfortable figure with a fuzzy gray ponytail and Yorkshire speech-his company is in the old textile-industry town of Rochdale. Our conversation was rocky, for I was never sure whom I was hearing-a practicing engineer or a technological evangelist. Engineers, like Mark Bader of Polaris, are reassuring men with every number and concept at the tongue's tip. Meiling was somehow different. I thought of 1930s aviation pioneers, combining technical and promotional talents. Is he a character from a Dick Francis novel, the canny Northcountry racing stable owner? His sharp lads train the ponies while he does the deals. We talked about plain bearings... pneumatic valves...titanium. Farreaching claims alternated with sensible, accurate observation.

His firm is small-10 people. A recent splash in the venerable English magazine Autocar explains his obscurity by saying that his prolific design work has been obscured by intellectual-property-rights agreements.

As it grew dark outside, Meiling pulled forth his watch, a gold-cased traditional timepiece with a glass back, revealing the workings within. He had a train to catch.

Melling's signature feature-three sparkplugs per cylinder-is prominent on the inline-Four. Each plug is topped by its own miniature coil, so the leads look like a bundle of skinny telephone wire. This is a twodeck engine; one split passes through the crank, the other through the two gearbox shafts. With pneumatic valves, there are no failure-prone metal valve springs. Instead, a small, engine-driven pump supplies air pressure that acts beneath inverted-bucket-style tappets that fasten to the valve stems. When the cam lobe lifts the valve, the gas under the tappet is compressed, and its pressure rises. This pressure acts as the valve spring.

For this 73.0 x 44.7mm engine, a 16,000-rpm (racing) redline is claimed. This is a high but not impossible piston speed of 4700 feet per minute. Combine this with an averaged, net combustion pressure of 190 psi and you get 175 crankshaft horsepower.

Every major casting had a different number (0001, 0004, etc.), a clever way to demonstrate that several casting sets exist. The starter sits behind the cylinders, driving through gears. The Denso alternator rides above the gearbox. Total width is 17.7 inches. This engine has individual coolant entries for every cylinder, so each receives equal flow. Intake passes through a barrel throttle whose cylindrical housing is cast as part of the head. Barrel throttles eliminate sliding friction, and place the throttle function as close as possible to the valve. This permits a very short intake length-perhaps as little as 5 inches. No water manifolds, fuel injectors or stacks were fitted to this very clean, nick-free display unit. A show dummy?

Meiling had said jovially, patting the 750, "It's a runner."

With capped exhausts, who's to know? A beautifully machined 25mm, 13-spline output shaft protruded from the gearbox, so I spun it. I was rewarded with the satisfying clunk of gear dogs.

Nemesis provoked the most questions. "Can I see a V-Eight crankcase?" someone asked. "Come up to Rochdale and you'll see one. Actually there are 10 sets now, but they're all out for machining. Come in a week," was Melling's reply. In the bar, Meiling had begun with a challenging announcement: "No one in this gathering has asked the one ques tion that would be first on my list. Is it fly-by-wire? It is."

Fly-by-wire is an aviation term. "Do you mean," I asked, "that the V-Eight's throttles are turned by stepper motors, with no cable control to the twistgrip?" Melling nodded.

Fly-by-wire is an aviation term. A computer flies the aircraft, the pilot tells the computer what he wants, and it does only what is actually possible. Applied to F-i cars, it meant central ized anti-spin, ABS and startline launch control-no direct control from throttle pedal to engine, for example.

"Do you mean,"I asked, "that the V Eight's throttles are turned by stepper motors, with no cable control to the rider's twistgrip?"

Melling nodded. We moved on to active suspension. The press kit describes a system that squats the whole machine during acceleration, making it low like a dragster. This allows more acceleration to be used before a wheelie occurs. A back of-the-envelope calculation showed long ago that such a system could lower Daytona lap times by a second and a half

There was more to think about, as Melling continued, "If the machine is sliding, and the rear wheel gets grip again, you have the makings of a high side. But with this system, the suspen sion locks in that position, so it can't rebound and throw the rider."

"Do you mean," I asked, "that all suspension motion is controlled by hydraulic cylinders, powered by an engine-driven pump?" Again, he nodded: "Moog valve on the front. Moog valve on the rear." "Are there suspension springs as well?" I wondered aloud.

"There are, but only to reduce the load on the pump," Melling responded. There is nothing wrong with any of the numbers claimed for the engines described. Throughout, attainable piston speeds and combustion pressures are all that is claimed. Belief is strained, how ever, by the idea that so much chassis and control technology can be success frilly sold to motorcyclists. Perhaps this part has more to do with marketing the Norton name for the future than with saleable vehicles in the present. Quantity production is the key to price.

some ciue to wnat urives tnis opera tion came from the assertion that, "In five years, Norton will be launched into aerospace."

I n the Orchid Room, we saw the results of a lot of money spent. The fine sand-castings of the Manx were smooth, competent and persua sive. The rim-mount brake discs of the Nemesis were unfinished and less impressive. And the suspension of this mockup was definitely conventional.

"Why motorcycles?" I asked Myron Calof, of Aquilini. "Why not start with, say, fuel-saving wingtip kits for popular bizjets?" "That would be a good idea, too," was his cheerful reply.

Once I got home again, I called Les McTaggart, who has left March and is now a consultant to an Indy Racing League team. He had not been at the meeting. He carefully made no com ment on NM!, but speculated as to how much of this technology, applied to a motorcycle, can be successfully sold.

"Technology has an associated cost," he summed up. The original March concept, he related, had been relatively simple-a state-of-the-art engine in an all-carbon-fiber chassis. Sold in quan tities of perhaps 250 units a year, at about £25,000 ($37,500), this would shortly have seen them into the black, he thought.

"Nemesis is similar to our Super bike," McTaggart said, but with metal instead of carbon-fiber in the chassis. "I wish them all the luck in the world," he concluded. "Who knows? At this time next year, there could be 2000 motorcycles a month coming out of the Shenstone factory."

AS I walKed away trom tne L)or chester, then glided down the long escalator into the subway, I thought over what I'd just seen. Because so few journalists were present, the show wasn't for us. For whom? For the quiet men in dark suits, then. I later learned that at least several of them were Melling's parts and tooling suppliers, seeking the assurances that good busi ness is based upon. For various fiscal reasons, the earliest possible produc tion of at least one model is important. Because Cycle World is not the Wall Street Journal, that's not our affair.

I want to see new-era technologies like pneumatic valves and active sus pension enter the motorcycle worldprovided costs can be managed. They can solve actual problems, break diffi cult design compromises and over come resistance to new ideas. Cost depends on volume, but a first step is often taken by a low-volume producer, like Bimota, offering premium prod ucts. Norton Motors could do good business, first displaying arcane new technologies in premium vehicles, then finding efficient ways to produce or license them to wider markets. Cross your fingers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue