Instruments of control

TDC

Kevin Cameron

I HAVE A LOT OF ODDS & ENDS IN MY shop—strange things like an amazingly heavy tungsten brick. Another of these items popped into my mind the other day when I was reading about how Danny Eslick’s 1125 Buell has paused from winning AMA races after a seemingly unstoppable run of firsts. The item is an ordinary camera iris. By moving a small lever, its round orifice can be varied from a maximum of 65mm diameter down to about 8mm. I used to joke that one day, race-sanctioning bodies would require that such a variable orifice be placed in each engine’s intake, and that it would be remotely controllable. If a certain competitor proved to be excessively skillful, or the vehicle too capably engineered, Race Control could simply dial the leader back into the pack.

Now I must dust off that concept and think again. Many of the machines now competing in certain race series have computer-controlled secondary (or even primary) throttles. The rider tells the computer the power level desired, and the computer delivers the power level that the rear tire can actually transmit at that moment. Because some of these systems demonstrably work a bit better than others, there is a steady drumbeat of calls to require the use of standardized engine controls that are returned to officials upon race completion. These controls would presumably “level the playing field” by making the same technology available to all competitors.

But if all competitors’ engine controls came under sanctioning body management, certain temptations would present themselves. First of these would be the temptation to implement managed parity by writing software capable of influencing each bike’s throttle opening in a systematic way. In effect, the computer-controlled throttles would become today’s equivalent of my imaginary radio-controlled camera-iris-inthe-intake. No rider would ever again run away with a series. Instead, each contest would be a heart-stopper, and the championship would come down to the last race. To give this a name, we could call it “Active Intake Limitation.”

Mind you, races can be controlled in other ways, such as use of the yellow flag or by periodic bunchings-up behind a pace car. But we do live in a digital era now, and the improved control offered by digital solutions springs to mind.

The second temptation concerns competitor discipline. Older race-goers know there was no love lost between two-time national champion Gary Nixon and long-ago AMA referee Charlie Watson. Our current era offers parallel examples of chronic friction between riders and the race organization. With Active Intake Limitation, such a rider could soon find himself finishing far downfield and would therefore have cause to reconsider his attitude toward authority.

There is also the successful example of the NHRA’s management of Pro Stock Motorcycle drag racing. Formerly just one motorcycle class among many others and dominated by older Suzukis, Pro Stock was revitalized by allowing the construction of what we may call “synthetic competitors’-engines designed from the start specifically for drag racing and then arbitrarily badged as Harleys or Buells in order to bring the many adherents of those brands to the ticket windows. It has worked extremely well, and small adjustments to weights and technology have since kept the big Twins winning most of the events, with just enough Suzuki action to maintain suspense.

What is important here is the crucial relationship between the spectator and the results. Seen in business terms, race results are a product offered by the sanctioning body. If the customer-the ticket buyer-doesn’t like the product, a more attractive product must be developed and put in its place. If, just as a purely hypothetical example, our focus-group work reveals that hundreds of thousands of Czech citizens would attend our races if a Jawa were to finish regularly in the top-three, it would be our clear responsibility to our stockholders to consider how to achieve that result.

It also happens that certain riders are crowd favorites, even though a rational assessment of their chances indicates they have little likelihood of success. But what if we could arrange such wins? What effect might that have on attendance? There’s nothing quite as exciting as seeing a beloved underdog charge through the pack from the back of the grid to win, or at least make the podium.

Finally, there is a gray area that offers too many intriguing possibilities to be ignored. From time immemorial, there have been persons who have sought to know the outcomes of sporting events before the fact. Such persons are always at hand, willing to pay well for the information they seek. When it comes to generating revenue streams, this is potentially the biggie. All business involves risk, and there is risk here aplenty-the risk of discovery and legal prosecution. Yet the shenanigans of Enron and certain other major corporations suggest that in an increasingly competitive business environment, the envelope of what is morally defensible in pursuit of profit must continually expand. As they say in government, “All options must remain on the table.”

It has been asked whether racing is about lap times or about spectators. If it is truly about the latter, we must find out what they really want-and give it to them. What if we discover that what they want is crashes? Do we say, “No! Absolutely not! Never!”? Or do we do as industry has demonstrably done in the past: request that our legal department investigate the trade-off between the foreseeable lawsuits and the possibly increased income? Racing cannot be a riders’ benevolent society. Business is business.

Pinch me now, so I can awaken from the above nightmare. No sanctioning body would ever want the temptations described. Leave the engine controls to the teams.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontTen Rest, 2009

August 2009 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Guy of the Moment

August 2009 By Peter Egan -

Departments

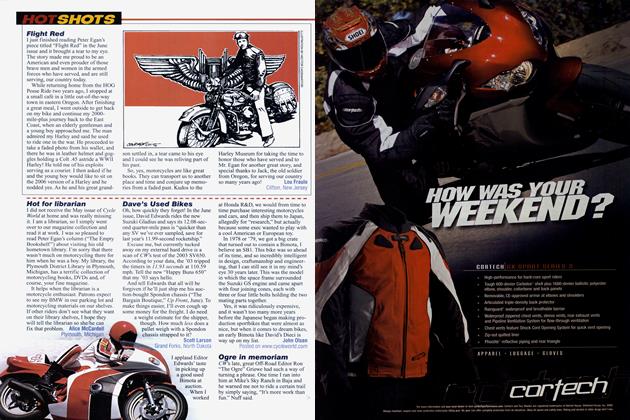

DepartmentsHotshots

August 2009 -

Roundup

RoundupElectric Arrival

August 2009 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago August 1984

August 2009 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupØ Risk?

August 2009 By Laurent Benchana