PUTTIN’ ON THE RITZ

Dissolution of the Bad Boy Image?

There is something pleasantly odd about the scene. Three hundred vintage motorcycles occupying the 18th fairway of the swank RitzCarlton in Half Moon Bay. For the third year running, the immaculately manicured grass of the luxury hotel’s golf course has been made available to display an impressive array of cherished, significant two-wheel iron that is The Legend of the Motorcycle.

Standing on the seaside patio, gazing out over this beautiful spectacle, I can’t help but think about an incident that took place 61 years ago in a small Northern California town just 70 miles from here that dramatically maligned the public’s perception of motorcycles.

The infamous events of a July Fourth weekend in the sleepy little town of Hollister have become biker folklore and contrast this atmosphere of smiling, grey-vested hotel staff and the parade of welldressed spectators sipping tall, thin glasses of champagne.

The incident came about courtesy of the 1947 Gypsy Tour Motorcycle Rally that had chosen Hollister for an Independence Day gathering. Some 4000 bikers descended on the small agricultural town, overwhelming its citizens and taxing the police force of seven. Police logs document about 50 arrests, mostly for drunkenness and traffic violations. Not a bad score given the circumstances.

Unfortunately, a writer covering the story for the San Francisco Chronicle decided to embellish the facts to secure some ink in the paper. The headline for his article was “Bikers Take Over Town.” He took it one step farther, publishing the now-famous staged photo of a drunken, slovenly biker reclined on his Hog, surrounded by a sea of empty beer bottles. The story went out over the wire and was picked up by local newspapers, culminating with publication in Life magazine. That image became the calling card for motorcyclists and threw us into a void of negativity that has taken 60 years to extricate ourselves from.

A real irony here is that the motorcycle clubs of that period had been formed, to a large degree, by returning G.I.s at the close of World War II. In many cases, these young men, forced into premature manhood by the horrors of war, felt alienated from the very country they had risked their lives for. They’d been unwittingly hardwired into adrenaline and found it difficult to re-acclimate to smalltown life. A good number of vets sought out former Army buddies, embracing the intense bonds of friendship forged on the battlefield. They scooped up surplus motorcycles, chopped and bobbed them, and set out to recapture their aborted adolescence. Hence, the motorcycle gang was born.

Unfortunately, Hollywood plucked a sensational script from the Hollister incident and stuck Marlon Brando on the seat of a Triumph, playing a hoodlum whose gang terrorizes a decent American enclave in The Wild One. Law-abiding citizens in small rural towns everywhere were dead-bolting doors and loading shotguns in anticipation of the seemingly imminent threat of invading motorcycle gangs coming to deflower their daughters. The film’s success launched a cottage industry of bad biker films throughout the ’50s and ’60s, depicting motorcyclists as unwashed, amoral hoodlums and perpetuating a lot of bad juju with the public. The emergence of truly menacing gangs with criminal overtones like the Hells Angels and the Pagans didn’t do much to assuage the image-even if they mostly bumped each other off in turf wars. If you rode a bike, you were trouble.

There were countermeasures, though. In the early ’60s, a simple ad campaign began to turn the tide of public perception: “You meet the nicest people on a Honda.” Suddenly America was given a fresh face for the motorcyclist. They were good, clean kids jetting off to class on their 50cc step-throughs. Steve McQueen helped curb some of the negativity, applying his superstar status and super-cool persona. Easy Rider was a monumental turning point, depicting its chopper-riding protagonists as introspective men who die at the hand of ignorant rednecks-not the other way ’round. The movie pretty much killed the exploitation biker film and put an end to Hollywood’s celluloid erosion of relations between bikers and the public. By the ’70s, a combination of Vietnam, the gas crisis, the struggling economy and the embarrassing disgrace of Watergate made Americans realize there were more pertinent threats to their wellbeing than the threat of marauding biker gangs-which had failed to materialize on their doorsteps after all. After two decades, the general public was forced to abandon the erroneous, archetypal image it had been fed and gradually began to accept motorcycles.

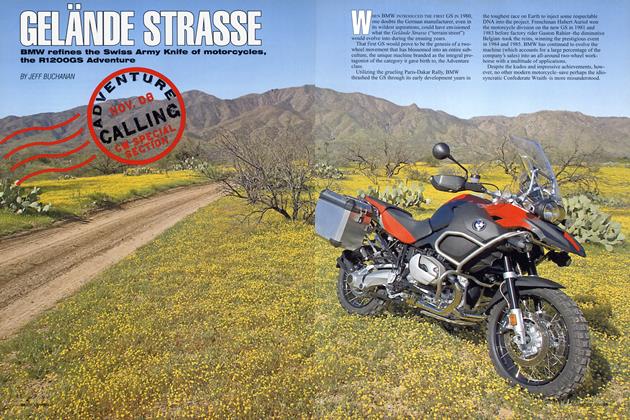

It’s Sunday morning, the day after the Legend event. The RitzCarlton’s greens men are carefully erasing the remnants of tread imprints left behind by glorious vintage machines. Sixty-one years after the spark of the Hollister “riots” ignited a maelstrom of bad blood and put us on a collision course with America, here we are, welcomed with open arms to the Ritz. As I pull out of the hotel on a BMW K1200GT, the white-gloved valet smiles and waves. We’ve come a long way, baby. Jeff Buchanan