FAMILY BUSINESS

Rayborn's Ride Returns

ALLAN GIRDLER

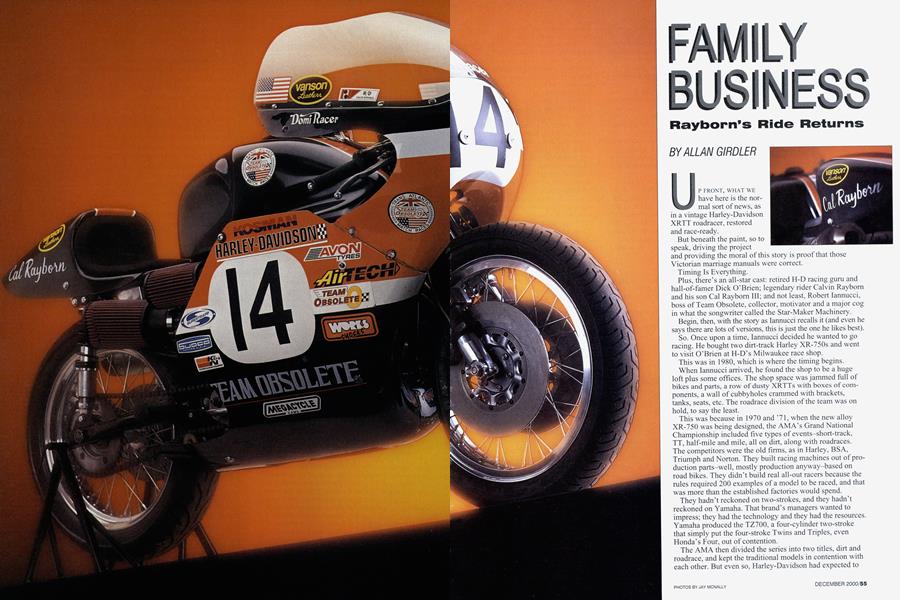

UP FRONT, WHAT WE have here is the normal sort of news, as in a vintage Harley-Davidson XRTT roadracer, restored and race-ready.

But beneath the paint, so to speak, driving the project and providing the moral of this story is proof that those Victorian marriage manuals were correct.

Timing Is Everything.

Plus, there’s an all-star cast: retired H-D racing guru and hall-of-famer Dick O’Brien; legendary rider Calvin Raybom and his son Cal Raybom III; and not least, Robert Iannucci, boss of Team Obsolete, collector, motivator and a major cog in what the songwriter called the Star-Maker Machinery.

Begin, then, with the story as Iannucci recalls it (and even he says there are lots of versions, this is just the one he likes best).

So. Once upon a time, Iannucci decided he wanted to go racing. He bought two dirt-track Harley XR-750s and went to visit O’Brien at H-D’s Milwaukee race shop.

This was in 1980, which is where the timing begins.

When Iannucci arrived, he found the shop to be a huge loft plus some offices. The shop space was jammed full of bikes and parts, a row of dusty XRTTs with boxes of components, a wall of cubbyholes crammed with brackets, tanks, seats, etc. The roadrace division of the team was on hold, to say the least.

This was because in 1970 and '71, when the new alloy XR-750 was being designed, the AMA’s Grand National Championship included five types of events—short-track, TT, half-mile and mile, all on dirt, along with roadraces.

The competitors were the old firms, as in Harley, BSA, Triumph and Norton. They built racing machines out of production parts-well, mostly production anyway-based on road bikes. They didn’t build real all-out racers because the mies required 200 examples of a model to be raced, and that was more than the established factories would spend.

They hadn’t reckoned on two-strokes, and they hadn’t reckoned on Yamaha. That brand’s managers wanted to impress; they had the technology and they had the resources. Yamaha produced the TZ700, a four-cylinder two-stroke that simply put the four-stroke Twins and Triples, even Honda’s Four, out of contention.

The AMA then divided the series into two titles, dirt and roadrace, and kept the traditional models in contention with each other. But even so, Harley-Davidson had expected to build and sell scores of XRTTs, the roadrace version of the alloy 750, which is more different from the dirt version than it looks.

There O’Brien was, with a loft full of XRTT chassis and parts, working for a company with financial, urn, concerns, when in walked a paying customer.

But not yet a most-favored-nation sort of customer. O’Brien sold Iannucci enough parts to convert his XR-750s into XRTTs.

This was 1980, remember, and vintage racing, thanks in no small part to Iannucci’s drive and efforts, was just getting underway. His Team Obsolete had money, expertise and talent. The team put Harleys into contention, at a place and time when Harleys were out of favor. So, the next time Iannucci dropped in on the racing department, he was allowed to buy a rolling chassis, the literal backbone for the XRTT seen here.

This is where things get iffy. The roller Iannucci and O’Brien pulled out of the comer of the loft may, repeat may, have been ridden by Cal Raybom.

Because this part occurred a quartercentury ago, we need to make a tragic comparison.

There are uncanny and unhappy parallels between Cal Raybom and the recently deceased Joey Dunlop. Both men were seemingly ordinary guys, People’s Champions, as the English press likes to say.

No fan who saw Dunlop or Raybom in action ever forgot it. To see either on a racetrack was to know, instantly, that you were witness to genius, an ordinary guy doing things no ordinary guy could do.

Because you’ve seen a man cancel the laws of gravity, repeal Newtonian physics lap after lap, you come to believe the man is invincible.

It follows that when Joey Dunlop was killed earlier this year in an obscure race in Estonia, we didn’t want to believe it and we took it hard.

So it was when Calvin Raybom was killed in 1973 at an obscure race in New Zealand.

Raybom’s legend lives, just as Dunlop’s legend will live.

Raybom is still a hero in England because in 1972, riding an out-of-date iron XR-750 built by Walt Faulk and competing against the factory’s wishes, Raybom dominated the Match Races, the big Brits vs. Yanks series of the day. That machine now lives in the AMA museum, donated by HarleyDavidson after the fact.

Raybom’s best bike, containing a host of wonderful improvements the production versions never saw, is the property of Dick O’Brien’s daughter-okay, he’s the man who maintains it, but it’s in her name, and it’s all documented.

When jazz legend Eubie Blake celebrated his 100th birthday and the reporters asked for comments, Blake famously said if he’d known he was gonna live that long, he’d have taken better care of himself.

By that token, if the HarleyDavidson team had known they were making history 20 or 30 years ago, they would have taken better notes.

But they didn't. There are best bikes and spare bikes, and sets of gears and wheels and carbs and extra tanks, seats and so forth. Parts get swapped back and forth in the shop and at the track. There are engine numbers-in fact, Harley traditionally has begun serial numbers for the team engines with 5, while the production XRs begin with zero. There are engine-testing records and sometimes the team notes will show that Raybom’s engine at Imola in 1972 was, say, 501, Brelsford’s was 502 and Pasolini had 503. You can check the photos and see who had disc brakes and who retained the front drum.

But the rest of the history can be, and is, debated.

Timing again. When Iannucci had earned his reputation, paid his dues and was allowed to buy the ex-team roller, the one he dragged out had “Cal Rayborn” written on the seat and “Cal” on the fuel tank in magic marker.

“If the HarleyDavidson race team had known they were making history 30 years ago, they would have taken better notes.”

The research Iannucci has done, which is a lot, tells him the roller he got, the foundation for the machine seen here, is ex-Raybom.

Iannucci says his evidence implies that this machine-well, the frame and some parts-was the XRTT Rayborn rode in the 1973 Match Races and is one of the three XRTTs the star rode in his time with the factory team.

O’Brien says he doesn’t exactly doubt it, not in so many words, but by his reckoning Rayborn rode 18 factory bikes, including six XRTTs, and while the roller Iannucci bought may indeed be the ’73 Match Race machine, he won’t say so as a fact. Rayborn’s son, whom we’ll meet shortly, takes the third way out and says the bike is, “a replica of what my dad raced.”

That, it surely is.

The frame for the number-14 bike is a factory-supplied XRTT unit-duplex engine cradle, backbone wrapped around the front cylinder head, twintomahawk castings for the rear engine mount, just as it was introduced in 1972. There are two shocks and the fork is a 35mm Ceriani.

The engine is a period-piece XR-750. There’s no dispute here. Iannucci bought the chassis minus engine and got the powerplant elsewhere. He’s been told it was used when new by Terry Poovey, the veteran flat-tracker who’s still winning nationals; albeit by a quirk of fate he’s also the only Grand National contender still riding a Honda, the RS750 V-Twin that was, as the joke has it, the improved version of the XR-750, built by Honda because they could afford it and Harley couldn’t.

That brings back the third part of the timing of this saga.

After Iannucci had the parts seen here, plus some spares, and after Dick O’Brien had retired to help run a NASCAR team and then just plain retired, Iannucci went to visit the Milwaukee storehouse.

And found the cupboards bare.

He says he was told that provisions in Wisconsin tax law give generous benefits for the destruction of inventory. One day without warning, the story goes, the accountants swept down on the shop and padlocked it. Then they brought in the movers and the dumpsters and hauled away all the frames, tanks, brackets, everything to do with the now-obsolete, now-canceled roadracing program.

They crushed the whole collection, all the XRTT inventory, while taking pictures of the carnage so as to prove the tax people that all the goods had been destroyed.

“To see Cal Rayborn in action was to know, instantly, that you were witness to genius, an ordinary guy doing things no ordinary guy could do.”

O’Brien wasn’t there. And nobody who knew OB at the height of his forceful leadership believes for one moment that if he had been there, this desecration could have happened.

For here and now, the moral is if some of the more enthusiastic racers and collectors, Iannucci and peers, hadn’t gone after what they did, and been allowed to preserve and use it, works of art like the one shown here would not be here.

In another sense, timing has influence here because this XRTT is a current vintage racer and there are rules, some enforced and some not, that are followed.

This XRTT engine began as professional equipment, dirt or pavement. It’s maintained as an engine of its time. The camshafts are to Mert Lawwill-spec and the carburetors are round-slide Mikunis, as seen in 1973. But the ignition is electronic with tailored advance curve, done by ARD inside what looks like the old tractor-era magneto on the front of the gearcase. The exhaust system is capped by a pair of SuperTrapp mufflers, which weren’t available back then, but are used now because they enable the engine to pass sound checks as well as perform on a par with the old megaphones or boom-boxes.

The rules don’t prohibit learning through practice and the tuners now can get 100-plus horsepower from the alloy XR engine that delivered 70-plus when new. But because tuning to the limit is risky and expensive as well as out of the spirit of vintage racing, the engine has been kept mostly original and produces 80 or so bhp, enough to do the job and pass the tests.

The brakes are done in the same manner. When Honda introduced the 750 Four, that model came with a front disc brake. It took a couple of years before everybody was convinced discs were better than drums. During the transition and as part of the sport, Honda allowed rival factories to list the Honda brakes as racing parts, which is why some of the 1972 Harley factory XRTTs had Honda disc brakes.

And that’s how this Harley came to be wearing Japanese brakes, except that for safety reasons the rules allow upgrades, which explains the revised caliper mounting and the Kosman castiron rotors done in the CB750 style.

There’s a subtraction, too, in that this engine uses only one oil-cooler while back then team bikes had two. Iannucci says this is because they’ve now learned how to better control oil flow to, from and within the dry-sump system.

There’s less oil drag, which means less friction because the insides of the cases are polished to a mirror finish, breather timing is corrected and the oil lines are enlarged, so there’s less heat to shed.

The fairing, big tank and seat/tailsection are all full-factory. Team Obsolete also has smaller tanks and fairings for sprint races.

The action photo on the next page was taken in September, 2000, at Seattle International Raceway, in the Washington Motorcycle Road Racing Association’s season finale. Riding on that occasion was Calvin Raybom III.

The use of that III tells part of the story. Conventional mies for English grammar and etiquette say that if the father is John Jones, the son is John Jones Jr. He, the son that is, becomes John Jones at the father’s death. The grandson, who began as John Jones III, also moves up.

There are times this doesn’t happen. Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. kept the Junior all his life because that’s the way he became known. More recently, the former Kenny Roberts Jr. now appears at the races as Kenny Roberts because he’s in line to be world champion while his dad’s only a former world and national champion.

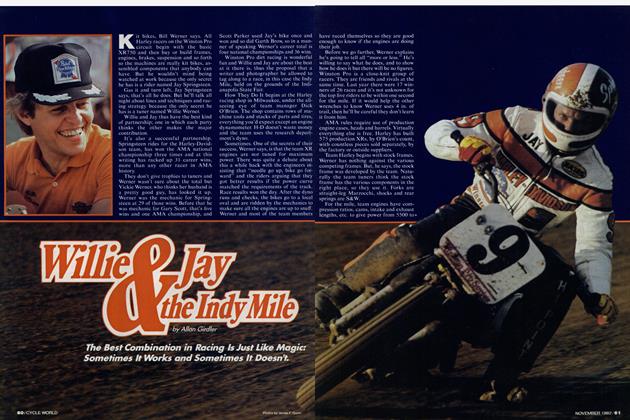

Cal Rayborn III still carries the III. His dad never used the Junior because he was famous and his father wasn’t. But the son, Cal III that is, has a tough act to follow. Iannucci says the son has his father’s talent, while there’s no question he hasn’t had his father’s success.

Cal III knows this all too well. He knows racing and went with his dad to the events when he was a kid. And he, the son that is, has had some good professional rides. But not lately.

Rayborn parries the ever-present question about his age with, “Old enough to know better.” He says the problem was that he didn’t take his career seriously enough when he was young. Rayborn, for the record now 40 years old, lives in Idaho. He owns a repair shop, and revises the Harley slogan into, “If it’s broke, I fix it.”

"Rayborn III and old Number 14 won both races, lapping most of the modern bikes in the process."

When Iannucci restored his XRTT as a genuine ex-Calvin Raybom bike, he had the obvious notion: Have the son ride Dad’s ride.

The results have been, well, promising. Number 14 turned the fastest lap at the Dutch TT Classic at Assen, came in second at a festival in England and has been in the lead at least once, only to have the ignition go sour.

Raybom likes the program. He has no problem with the people who come up to tell him how much they admired his dad. So did he. Nor is there any question his name has opened doors that would have been closed to John Jones III.

Dad’s Harley, like your father’s Oldsmobile, is unquestionably dated. The footpegs have been raised because roadracers lean more now than they used to. Raybom has ridden current Superbikes and 250cc GP bikes and says the differences are so, urn, different as to defy comparison. The XRTT weighs 380-plus pounds and has maybe half the horsepower of current Superbikes.

No comparison, he says, except that if he had to choose one word to illustrate the difference, it would be either “weight” or “muscle.” That’s what it takes to make the 30-year-old racebike do what the rider wants. What does all this amount to?

For the moral of the story we shift to SIR, a combined road course and dragstrip, in a locale famous for rain.

On Friday, in practice, Cal and old Number 14 set a vintage lap record.

On Saturday, in the season finale, the combo won the first heat, in the pouring rain.

In the second heat, Cal had the lead when the front tire lost pressure. He held on until the last lap, tire sagging, still in the rain, and managed second.

His post-race comment, “I just kept the front light,” must set some sort of record for understatement.

Sunday was club-race day, with the vintage and modem machines running at the same time, on the dry for once. Raybom and Number 14 won both of their races, lapping most of the modem bikes in the process and entertaining the crowd with straight-length wheelies at the same time. Clearly, he does have his dad’s talent, to which Iannucci adds that the son also has a rare talent for knowing what the bike’s doing, and for being easy on equipment. (Raybom would welcome, it seems fit to comment here, a return to the Pro ranks.)

But that’s merely the factual part. Iannucci found himself more moved by the number of people who walked over, for pictures and photos of the bike and of Raybom and his own children, two girls and a boy, who came to the races with Dad.

To hear a field of Harley XR-750 flat-trackers is, well, to understand why the AMA national series is called the Rolling Thunder Show.

To hear a lone XR-750 roadracer goes beyond that. The 10-minute warmup drill in the pits always drew a crowd, while in the stands, fan after fan cupped hands to ears and turned, following Number 14 all the way around the circuit.

The sound, like Cal Raybom and his Harley XRTT, is an experience not to be forgotten.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontCafé Society

December 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOrthopedic Bike

December 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCPaying the Price

December 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

December 2000 -

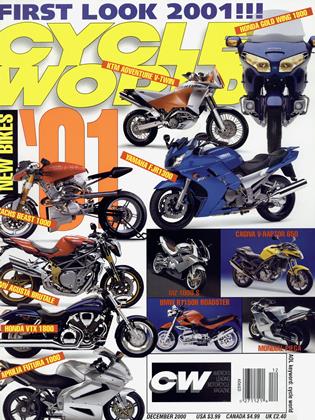

Roundup

RoundupKawasaki Goes Green

December 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupEnter the Drako?

December 2000 By Brian Catterson