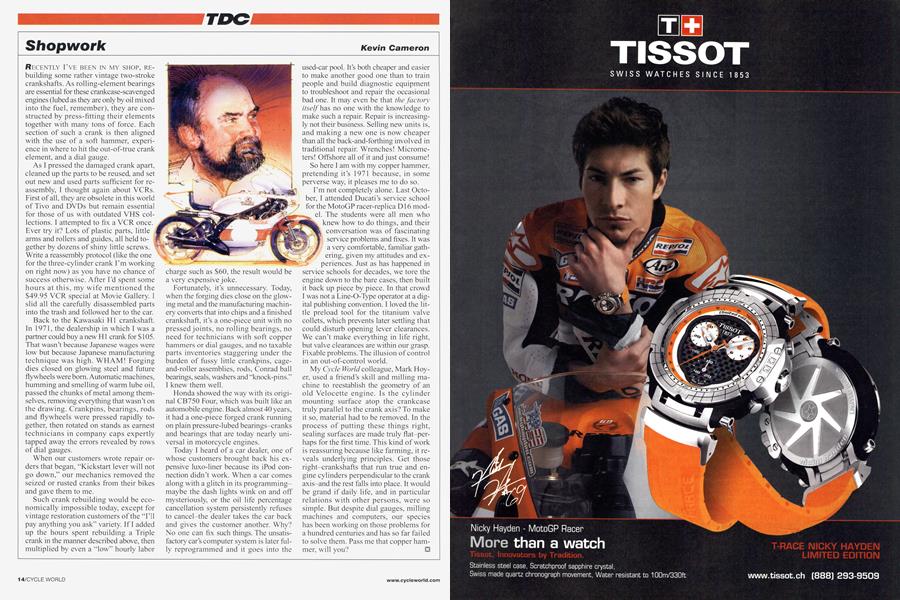

Shopwork

TDC

Kevin Cameron

RECENTLY I’VE BEEN IN MY SHOP, REbuilding some rather vintage two-stroke crankshafts. As rolling-element bearings are essential for these crankcase-scavenged engines (lubed as they are only by oil mixed into the fuel, remember), they are constructed by press-fitting their elements together with many tons of force. Each section of such a crank is then aligned with the use of a soft hammer, experience in where to hit the out-of-true crank element, and a dial gauge.

As I pressed the damaged crank apart, cleaned up the parts to be reused, and set out new and used parts sufficient for reassembly, I thought again about VCRs. First of all, they are obsolete in this world of Tivo and DVDs but remain essential for those of us with outdated VHS collections. I attempted to fix a VCR once. Ever try it? Lots of plastic parts, little arms and rollers and guides, all held together by dozens of shiny little screws. Write a reassembly protocol (like the one for the three-cylinder crank I’m working on right now) as you have no chance of success otherwise. After I’d spent some hours at this, my wife mentioned the $49.95 VCR special at Movie Gallery. I slid all the carefully disassembled parts into the trash and followed her to the car.

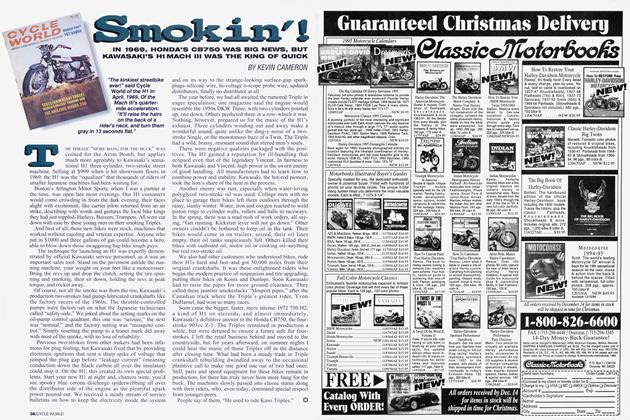

Back to the Kawasaki HI crankshaft. In 1971, the dealership in which I was a partner could buy a new H1 crank for $ 105. That wasn’t because Japanese wages were low but because Japanese manufacturing technique was high. WHAM! Forging dies closed on glowing steel and future flywheels were bom. Automatic machines, humming and smelling of warm lube oil, passed the chunks of metal among themselves, removing everything that wasn’t on the drawing. Crankpins, bearings, rods and flywheels were pressed rapidly together, then rotated on stands as earnest technicians in company caps expertly tapped away the errors revealed by rows of dial gauges.

When our customers wrote repair orders that began, “Kickstart lever will not go down,” our mechanics removed the seized or rusted cranks from their bikes and gave them to me.

Such crank rebuilding would be economically impossible today, except for vintage restoration customers of the “I’ll pay anything you ask” variety. If I added up the hours spent rebuilding a Triple crank in the manner described above, then multiplied by even a “low” hourly labor charge such as $60, the result would be a very expensive joke.

Fortunately, it’s unnecessary. Today, when the forging dies close on the glowing metal and the manufacturing machinery converts that into chips and a finished crankshaft, it’s a one-piece unit with no pressed joints, no rolling bearings, no need for technicians with soft copper hammers or dial gauges, and no taxable parts inventories staggering under the burden of fussy little crankpins, cageand-roller assemblies, rods, Conrad ball bearings, seals, washers and “knock-pins.” I knew them well.

Honda showed the way with its original CB750 Four, which was built like an automobile engine. Back almost 40 years, it had a one-piece forged crank running on plain pressure-lubed bearings-cranks and bearings that are today nearly universal in motorcycle engines.

Today I heard of a car dealer, one of whose customers brought back his expensive luxo-liner because its iPod connection didn’t work. When a car comes along with a glitch in its programmingmaybe the dash lights wink on and off mysteriously, or the oil life percentage cancellation system persistently refuses to cancel-the dealer takes the car back and gives the customer another. Why? No one can fix such things. The unsatisfactory car’s computer system is later fully reprogrammed and it goes into the used-car pool. It’s both cheaper and easier to make another good one than to train people and build diagnostic equipment to troubleshoot and repair the occasional bad one. It may even be that the factory itself has no one with the knowledge to make such a repair. Repair is increasingly not their business. Selling new units is, and making a new one is now cheaper than all the back-and-forthing involved in traditional repair. Wrenches! Micrometers! Offshore all of it and just consume!

So here I am with my copper hammer, pretending it’s 1971 because, in some perverse way, it pleases me to do so.

I’m not completely alone. Last October, I attended Ducati’s service school for the MotoGP racer-replica D16 model. The students were all men who knew how to do things, and their conversation was of fascinating service problems and fixes. It was a very comfortable, familiar gathering, given my attitudes and experiences. Just as has happened in service schools for decades, we tore the engine down to the bare cases, then built it back up piece by piece. In that crowd I was not a Line-O-Type operator at a digital publishing convention. I loved the little preload tool for the titanium valve collets, which prevents later settling that could disturb opening lever clearances. We can’t make everything in life right, but valve clearances are within our grasp. Fixable problems. The illusion of control in an out-of-control world.

My Cycle World colleague, Mark Hoyer, used a friend’s skill and milling machine to reestablish the geometry of an old Velocette engine. Is the cylinder mounting surface atop the crankcase truly parallel to the crank axis? To make it so, material had to be removed. In the process of putting these things right, sealing surfaces are made truly flat-perhaps for the first time. This kind of work is reassuring because like farming, it reveals underlying principles. Get those right-crankshafts that run true and engine cylinders perpendicular to the crank axis-and the rest falls into place. It would be grand if daily life, and in particular relations with other persons, were so simple. But despite dial gauges, milling machines and computers, our species has been working on those problems for a hundred centuries and has so far failed to solve them. Pass me that copper hammer, will you? □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue