CW EXCLUSIVE

MONSTER MOTARD

Behind the scenes with Ducati's category-busting Hypermotard

MATTHEW MILES

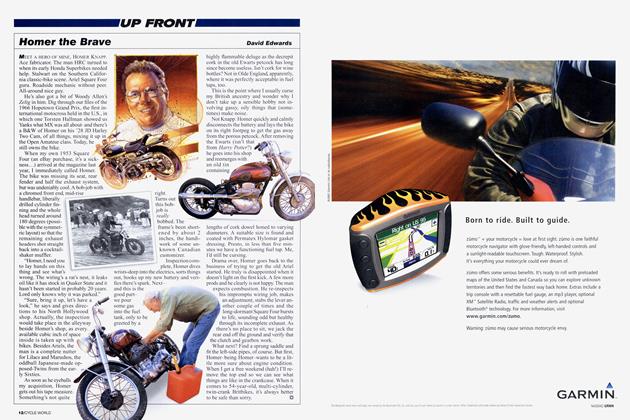

PIERRE TERBLANCHE DOESN’T PULL ANY PUNCHES. True to his South African roots, the Ducati designer tells it as he sees it—straight up, sugar-free. Well, most of the time.

I was seated across from Terblanche at a large conference table on the upper floor of the Ducati factory in Bologna, Italy. I had just asked him if his newest creation, the enthusiastically received showstopper-now-

go-for-production Hypermotard, was in fact “Pierre’s Revenge,” an in-your-face jab at those who panned the styling of the sales-floor-flop 999 superbike.

“I’m just happy people like the bike,” he responded sweetly.

Next question!

Then, shifting his weight, leaning toward me, bushy eyebrows becoming one, Terblanche offered this nugget: “I don’t think they would like it as much if the 999 hadn’t existed.”

He went on to explain how the 999 and the Hypermotard are very similar in their design treatments. “Maybe people needed a bit of preparation,” he mused. “The Hypermotard is not that much softer in its shapes, not that different from the 999. But people need time. They want stuff to be a little bit easier to understand.”

That goes for the view inside the factory, as well. “When the Hypermotard was first seen at the company, some people were a bit scared,” Terblanche reflected, picking up speed. “The front end didn’t look like other motards they’d seen. It wasn’t a carbon-copy of the other stuff.”

In fact, he related, they were actually upset. Those mirrors! You can’t do that!

Yes, you can, countered company president Federico Minoli. You not only can, you will. Don’t change a thing, he told Terblanche.

There were changes, of course, because putting any product into production isn’t snap-your-fingers simple. For instance, those slick (and highly effective, I might add, but more about that later) folding barend mirrors doubled as tumsignals in prototype form. No longer. Now, the LEDs are imbedded in the neighboring handguards.

“It would have been really difficult and from a technical point of view not correct,” pointed out project engineer Federico Sabbioni, a four-year veteran of the company who previously led production of the Multistrada and the SportClassics. “Pierre was probably not so happy to see his original proposal changed, but...”

To further illustrate his point, Sabbioni hefted a top triple-clamp from a SportClassic. The piece gleamed in the harsh office light. “It was really a great effort to create such a surface finish,” he said. “For Pierre, it was easy to think of such a part. He made only one, the only way he knows. The result was the one shown in Tokyo and, of course, it was appreciated by everybody. But making an aluminum part with a mold, giving it such a finish and making sure it is repeatable in batches of thousands was a problem.”

So it goes. Compromise is a word I heard frequently during my visit to the factory this past March. In Italy for a world-exclusive behind-the-scenes look at the 2008 Hypermotard 1100 and a ride on a prototype, I enjoyed unprecedented access; not only did I speak at length with Sabbioni and Terblanche, I spent considerable time as well with Minoii and Claudio Domenicali, product general manager.

Spacious and brimming with memorabilia, Domenicali’s office is located deep in the bowels of the factory in the Corse racing department. To enter that sparklingwhite environment, your escort-in my case, press officer Massimo Davoli-must first input an access code on a keypad on the wall in the hallway. If the code is recognized, a bank-vault-size, handle-free door swings slowly open. Cool-and a bit eerie. Are cameras recording my every move? Would I be allowed to leave?

“I think the Hypermotard is reflecting the spirit of the new products that Ducati will release in the future,” Domenicali teased. He further explained that when racing and product development were combined a few years ago and he was placed in charge, a new strategy was immediately put into.place.

“We made it very clear that Ducati is building sportbikes-that’s it,” he said firmly. His expression softening a bit, he added, “Of course, you can build many types of sportbikes-a pure sportbike, like

the 1098, or a sportbike with a different attitude, like the Hypermotard.”

This is not a new concept. In the U.S. alone, BMW, Buell, Husqvarna, KTM and Suzuki currently sell supermotard-style streetbikes ranging in displacement from 398 to 1203cc. But the Hypermotard is different. Very different.

For our get-together, Terblanche dug up his original design brief-written on September 19, 2004, and presented to management on January 18, 2005.

“My ideas were very clear about what this bike needed to be,” he said. “From Day One, it was an extreme streetfighter-street performance in a new aesthetic package. Like a huge Single on steroids, with very little weight, a cylinder added for low vibration and an increase of 40 horsepower.”

Sounds like fun, yes?

Terblanche had studied the motard scene as far back as 1998. At the time, his conclusion was that there was no market for a supermotard streetbike. In fact, he still believes there is no market for a real motard-an off-road-oriented, bigbore Single rolling on flexy, wire-spoke 17-inch wheels. That’s why such bikes haven’t sold in significant quantities.

“The research I did was very informal,” he said. “I took all the magazine articles on motards, and everybody said the same thing: They’re a lot of fun for the first week, then you can’t put up with the vibration, the lack of comfort, the lack of power. They’re only toys, very limited toys.”

Federico Minoli, president: “The Hypermotard comes from magic. Today, the bread and butter of our line comes from the process at our internal design center, which works in strict cooperation with the engineers and develops products that are the continuity of our line. The 1098 was born like that. The Desmosedici was born like that.

“I think we could miss something if we did not allow the creativity of a Pierre Terblanche. To generate something that is not foreseen, that is something we have to look at. And if we like it, then we can embrace it and put it into development. Because it could really add something magic. And that’s what I think the Hypermotard is doing.”

Not so the Hypermotard, despite its near-complete lack of protection from the elements. After all, basis is the CW Ten Best-winning, go-almost-anywhere, do-almost-anything Multistrada. Both bikes will even be produced on the same assembly line. Specifications-steering geometry, wheelbase, seat height, suspension travel-are virtually indistinguishable. Same goes for the engine, save for the intake and exhaust systems.

That being said, the only identical part is the single-sided cast-aluminum swingarm. Claimed dry weight is 396 pounds, 36 pounds less than the Multistrada.

While the Multistrada employs a singlepiece frame with same-size tubing front

to back to support the weight of a passenger and luggage, the Hypermotard uses a two-piece design-traditional big-tube latticework for the main frame, lighter, smaller-diameter piping for the subframe. Passengers are welcome on the Hypermotard, too; accommodations just aren’t as plush. Keeping with the minimalist theme, saddlebags are not offered.

Both models are fitted with fully adjustable Marzocchi forks and Sachs shocks, though the Hypermotard’s front end has larger-diameter 50mm sliders, not the 43mm legs used on the Multistrada. As was the case with the 1098, final damping and springing were decided following road and track testing by Vittoriano Guareschi, Ducati’s factory MotoGP test rider. “We wanted to have a race guy happy with the settings,” Domenicali confirmed. “If he is happy, the feeling is correct.”

Brakes up front are dual 305mm semifloating discs clamped by radial-mount four-piston Brembo calipers, with a single 245mm disc and two-piston caliper at the rear. The spec up front has changed since the showbike was originally unveiled in Milan, 2005, a decision made based on the results of an online poll. “Forty-five percent of the people wanted double discs,” said Minoii. “The engineers were saying, ‘For that level of power and weight, we don’t need double discs.’ Double discs cost twice as much as a single disc. But at the end of the day, if the Ducatisti want double discs, who are we to question?”

What truly differentiates the Hypermotard from the Multistrada-not to mention other Ducatis-is its ultra-aggressive riding position. Dirtbikes (or cruisers, for that matter ) are no longer part of the model line, but the relationship between rider and machine has more in common with the 1960s-era single-cylinder Scrambler that sits at the top of the stairs at the entrance to the lobby than with any modern-day desmo.

“The riding position allows you to ride over the handlebar, leaving a great part of the bike behind you,” Sabbioni explained. “That is not possible riding a Monster or a Multistrada. With those bikes, you sit almost in the middle; here, you sit almost on the gas tank.

“With your hands and feet in this riding position, you have really different feelings of how the bike must be ridden,” he continued. “From the beginning, I thought I would ride the Hypermotard the same way I ride a Monster or a Multistrada. After a few minutes, I realize this is possible, but it will never be as nice as it is to ride it like a real motard-moving the bike below you. It’s the sport interpretation of the supermotard way of riding.”

“Productionizing” the chinbar-overfront-wheel ergonomics was no small feat. Where, for example, did Terblanche envision locating the gas tank-under the seat? “It was clear that we were going to have problems fitting enough fuel,” he admitted. To that end, the production bike

is half an inch wider than the show model for a maximum fuel capacity of 12.4 liters-nearly 3.3 gallons. Don’t expect a 200-mile range. Similarly, to fit the SportClassic-derived airbox, volume was reduced until the associated loss in engine performance was deemed acceptable if not ideal. Just enough is just enough.

Had Terblanche gotten his way, the Hypermotard might be powered by a supercharged version of the doubleconnecting-rod 549cc Single from the early-1990s Supermono, still considered by many to be his finest work. “Some people-people not far from you in America-feel there is no substitute for cubic inches,” observed Domenicali. “We love cubic inches! That is the reason the Hypermotard is an 1100.”

Like the latest Multistrada, the Hypermotard’s dual-spark V-Twin boasts a capacity of 1078cc, up 86cc from the Monster S2R and SportClassics. Here, once again, packaging played an important role. From the get-go, it was clear:

For a V-Twin to fit, the engine had to be air-cooled. “When I presented the bike at Milan, I had a radiator sitting behind the curtain,” Terblanche recalled. “When somebody asked the question, ‘Why not water-cooled?’ I said, ‘Fit me this.’

“If you sit our bike next to a KTM 990 you realize why our bike is air-cooled and their bike is water-cooled,” he added. “Look at the results. It’s not the same thing. Our bike is small.”

Small, indeed. Terblanche said that if you were to roll a supermotard version of a Honda CRF450R motocrosser in front of the Hypermotard, “my bike would disappear.” Of course, supermotards aren’t terribly short, a fact that Terblanche is fully aware of. “The average wheelbase for a supermotard is 1495mm-58.9 inches,” he said. “But the Hypermotard is not a typical motard; it’s not a dirtbike with smaller wheels.” Wheelbase is 57.3 inches, a hair shorter than a Suzuki DRZ400SM but three-quarters of an inch longer than a KTM Super Duke and more than 3 inches in arrears of a Buell SuperTT.

Claudio Domenicali, product general manager: “I used to drive a BMW M3. I drove this car very slow in the city, but every acceleration, every bump in the road, gave me the feeling of a sports car. That’s exactly what we wanted with the Hypermotard. We wanted to build the experience from the time you start the engine out in the garage.

“Is it value when you start the motor in the garage? Yes, it is value. This is part of the deal, part of the feeling. That is why the Hypermotard shares some spirit with the 1098. It has a light flywheel. The way the engine accelerates in neutral-RRR, RRR-it’s crispy, you know?”

Federico Sabbioni, project engineer: “The Hypermotard is the pure expression of sport and fun. It can be described as the extreme Multistrada. You have almost the same chassis numbers and dynamic characteristics but in a smaller bike without anything that is not necessary.

“It will be easy to use in the city because it is very light and very quick. And, in my opinion, it will be the reference for fun in the mountains and on small tracks. Monza with a straight of more than half a mile would get boring, but a tight track and mountain roads with many curves are really the place for this bike.”

All of what I’d been told became clearer when, after several hours of meetings, I was finally able to swing a leg over a shiny red pre-production model. I’m 6-foot-2 with a 34-inch inseam, and placing both boots flat on the ground was not a problem. “My bike could be even taller,” acknowledged Terblanche, who is every bit as tall as I am. “But we want to sell to other people. We’d lose 20 or 30 percent of our market if we made the bike too tall.” Minimalism abounds-as it were. Nothing blocks your view of the road. “There’s no fairing, so it looks smaller than it actually is,” Terblanche noted, adding that the headlight is the smallest that could be homologated for road use. The instrument cluster isn’t much bigger than an iPod. As streetbikes go, the seat is narrow, with no seams or sharp edges. The folding footpegs are relatively low and have removable rubber inserts.

For the first two days of my trip, the weather had been cold and rainy. So when we were greeted the following morning by patchy blue skies,

I was more than happy to drag my helmet and leathers downstairs to breakfast. The plan was to ride two bikes: a mix-n-match, production-spec prototype (complete with battle scars) and a glossy, photo-studio-ready machine that could not, Minoli warned me, be crashed “under any circumstances.” I would ride the former in the morning on nearby twolane roads to gather my impressions and the latter just for pictures in the afternoon around the test track behind the factory.

First order of business was to adjust the mirrors. Made by a top trucking supplier, the triangular design rotates on a fully encapsulated ball. Once in position and the ribbed wheel locked down, the mirrors don’t move. Despite their small size, the mirrors work exceptionally well, offering an excellent view of trailing traffic. For traditionalists, Ducati will offer a kit to move the mirrors to conventional locations atop the handlebar.

Leaving the factory and making my way into the Italian countryside, I was blown away by the flexible nature of the DSI 100. At low rpm, the perfectly injected engine is so easy-going that it seems almost out of place on such an aggressive machine. The earlier 992cc version was a personal favorite, but this uprated powerplant is far better-smoother with even more low-end grunt.

Pierre Terblanche, designer: “I’ve always liked motards and similar bikes. When I worked for Massimo Tamburini, I had a Moto Morini 500. I took off the 21 -inch front wheel and put on an 18-inch front wheel from a custom bike. I stuck clip-ons on top of the triple-clamp and I made my version of a motard. That was 1991.

“I think the Hypermotard is a bit of a hooligan’s bike. I think people will go faster on it and feel happier. It encourages you to go quickly because you feel in control. It makes an average rider feel pretty confident. I suppose that’s the sign of a good bike.”

During my walkaround the previous afternoon, I had inquired about maximum revs-in typical Ducati fashion, the tachometer has no redline. Neither Sabbioni nor Terblanche knew the answer. I found that odd-until I rode the bike. The engine pulls so well from down low that spinning it all the way to 8500 rpm seems pointless. It’s probably a good thing the Hypermotard doesn’t have a Buell-like wheelbase; as it is, wheelies come easily.

On the Hypermotard, you attack corners-head low and eyes focused, elbows pointed toward the sky. Narrow roads seem wider, as if your lane were expanded half again. Pavement imperfections disappear into the long-travel suspension. Brakes are outstanding-progressive with loads of power.

Partial credit for all this performance goes to the prototype’s S-model trim: TiN-coated Marzocchi fork, Öhlins shock, forged-aluminum Marchesini wheels, Brembo monobloc front brake calipers and sticky Pirelli Dragon Super Corsa Ills. Mark down the rest to good design. Simply put, it’s just a fun motorcycle. If you lived in New York City and never ventured out of the city limits, you would still be enter-

tained by the acceleration and the wheelies and the stoppies. San Francisco may well deem the Hypermotard the Official Motorcycle of The City. Stunters should love it, unloading their CBRs and GSX-Rs and Rls like yesterday’s meatloaf.

If I were to criticize any aspect of the bike, it would be the position of the asymmetrical-length, span-adjustable levers: They’re too high for my tastes. Unfortunately, they’re “pinned” in place, no doubt for liability concerns. Terblanche talked about putting grooves in the bars for a range of adjustment, but that feature didn’t make it to production. Too bad.

Over a delightful Bolognese meal that night, Terblanche suggested traditional hardcore sportbikes sell well because buyers have been told that it’s cool to be uncomfortable. The Hypermotard could change all that.

“But how do you alter the way people think?” I countered. “How do you get the typical middleweight or Open-class sportbike buyer to trade his clip-ons and fairing for a wide motocross-style handlebar and faux radiator guards, to take a chance on something new and different?”

Smiling broadly, he replied, “That’s your job, isn’t it?” □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue