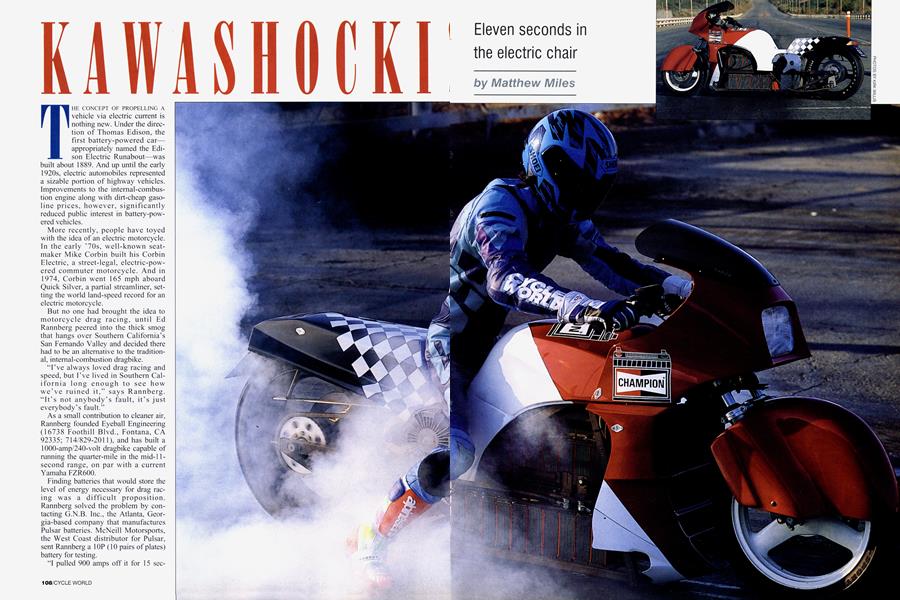

KAWASHOCKI

THE CONCEPT OF PROPELLING A vehicle via electric current is nothing new. Under the direction of Thomas Edison, the first battery-powered car— appropriately named the Edison Electric Runabout—was built about 1889. And up until the early 1920s, electric automobiles represented a sizable portion of highway vehicles. Improvements to the internal-combustion engine along with dirt-cheap gaso-line prices, however, significantly reduced public interest in battery-powered vehicles.

More recently, people have toyed with the idea of an electric motorcycle. In the early ’70s, well-known seatmaker Mike Corbin built his Corbin Electric, a street-legal, electric-powered commuter motorcycle. And in 1974, Corbin went 165 mph aboard Quick Silver, a partial streamliner, setting the world land-speed record for an electric motorcycle.

But no one had brought the idea to motorcycle drag racing, until Ed Rannberg peered into the thick smog that hangs over Southern California’s San Fernando Valley and decided there had to be an alternative to the traditional, internal-combustion dragbike.

“I’ve always loved drag racing and speed, but I’ve lived in Southern California long enough to see how we’ve ruined it,” says Rannberg. “It’s not anybody’s fault, it’s just everybody’s fault.”

As a small contribution to cleaner air, Rannberg founded Eyeball Engineering (16738 Foothill Blvd., Fontana, CA 92335; 714/829-2011), and has built a 1000-amp/240-volt dragbike capable of running the quarter-mile in the mid-11second range, on par with a current Yamaha FZR600.

Finding batteries that would store the level of energy necessary for drag racing was a difficult proposition. Rannberg solved the problem by contacting G.N.B. Inc., the Atlanta, Georgia-based company that manufactures Pulsar batteries. McNeill Motorsports, the West Coast distributor for Pulsar, sent Rannberg a 10P (10 pairs of plates) battery for testing.

“I pulled 900 amps off it for 15 seconds. I thought that if it takes me more than 15 seconds to cover the quartermile, I might as well stay home,” laughs Rannberg.

Eleven seconds in the electric chair

Matthew Miles

The long, narrow design of the Pulsar batteries made fabricating the chassis a simple affair. “I used 4130 square tubing,” says Rannberg. “It’s really light and super strong. That motorcycle could probably stand a small-block Chevy in it without torquin’ the chassis.” The chassis was completed with a Kawasaki KZ440 fork and a Ninja 250 front wheel; a Kosman rear wheel wears an 8.5-inch Goodyear slick. Rannberg’s electric motor of choice is a fourbrush, twin-bearing unit built by AdvancedDC Motors. Unlike internal-combustion engines, electric motors are downrated for continuous-duty operation, which in the case of Rannberg’s series-wound motor is a rather unimpressive-sounding 20 horsepower. But, according to Rannberg, an electric motor of this type is capable of putting out five times its rated horsepower for a short period of time.

With approximately $10,000 invested in parts and labor, Rannberg was ready to test his invention. “Originally, I ran the bike at 192 volts, using 16 of the 10P batteries,” he says. “The first time we went out, it ran in the middle 12s at about 101 miles per hour.”

Even though the bike had already surpassed his initial expectations, Rannberg knew it was capable of even better performance.

“It was geared low enough to get out of the gate good, but it just wouldn’t pull at the other end,” he says. “So 1 put a taller gear in, and it started running a little faster. Then I decided to try a twospeed B&J transmission and take out the slipper clutch. But all we did was break the chain. So we put the slipper clutch back in, and the times immediately fell into the middle 1 Is.”

Two relays and a pair of large diodes control the electric charge. Closing the first relay-by opening the throttle-puts the twin battery packs in parallel. As the throttle is fully opened, the second relay is closed, changing the arrangement from 120 volts in parallel to 240 volts in series.

“Initially leaving the line, it’ll pull 1000 amps,” says Rannberg. “The voltage dictates the speed of the motor, while the current dictates the torque that the motor puts out. That’s why an electric motor has such tremendous power at low speeds.”

Since ly powered there isn’t dragbikes, a class for Rannberg electricalruns the bike in conventional bracket racing, where consistency is paramount. The electric bike has won its share and has surprised more than a few of its competitors. “They just don’t realize how hard this thing pulls for the whole quarter-mile,” says Rannberg.

But the future of his electric dragbike is questionable. “I am torn between continuing with this project or going on to other things, like building an electric street motorcycle. If I do that, I’ll probably donate the dragbike to Don Garlits’ drag-racing museum. I was hoping this bike would generate enough interest to start a class, but it seems like everyone’s in awe of it, although it’s really a simple motorcycle,” says Rannberg.

Whatever the final outcome, Ed Rannberg has achieved success with his electric dragbike. And to someone who has seen Southern California go from an undeveloped desert to a glut of bedroom communities layered in smog, electricity may be more than just a sensible solution to air pollution. It could be serious fun.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontUncle George's Last Ride

April 1992 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Enchanted Vagabond

April 1992 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCRocket Fuel

April 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1992 -

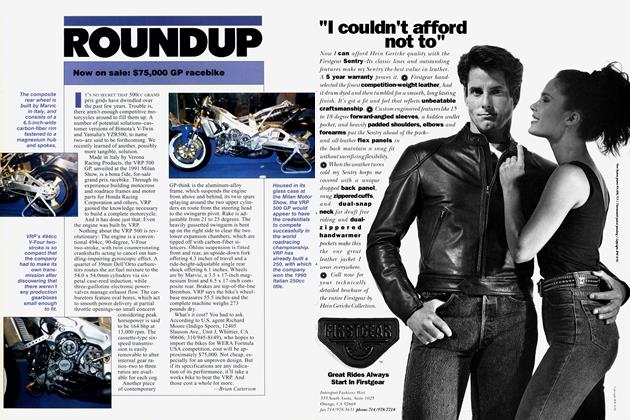

Roundup

RoundupNow On Sale: $75,000 Gp Racebike

April 1992 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupKtm Comes Back From the Brink

April 1992 By Alan Cathcart

Current subscribers can access the complete Cycle World magazine archive Register Now

Matthew Miles

Feature

-

Features

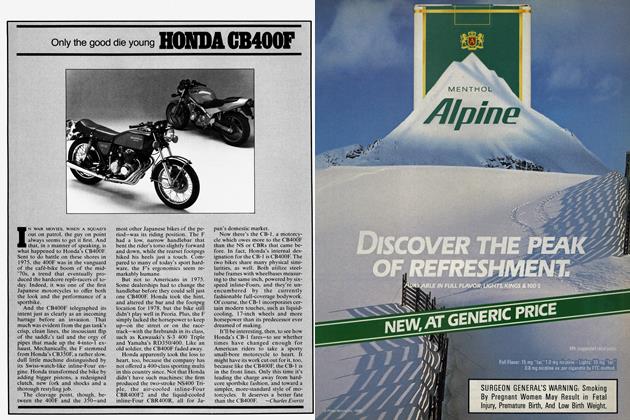

FeaturesOnly the Good Die Young Honda Cb400f

APRIL 1989 By Charles Everitt -

Special Features

Special FeaturesFrank Heacox Sells Helmets. Lots of Them. But He Opposes the Helmet Law. He Is, You See, A Motorcyclist. And We Can Thank Our Lucky Stars.

APRIL 1970 By Dan Hunt -

Features

FeaturesEfi At Last!

APRIL 1997 By Kevin Cameron