Project repellent

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

THERE'S AN OLD SAYING THAT YOU SHOULD be careful what you ask for, because you just might get it.

This is an expression you hear most often when people are talking about marriage or war. They say things like "I bet that attractive gal drinking double shots of tequila would be a fascinating date," or "It sure would be cool to fire a 30-caliber machine gun out of a helicopter door!"

The next thing you know they're in big trouble. In over their heads.

It can happen with motorcycles, too. Just a few weeks ago, I became a victim myself.

Seems I mouthed off and told all my friends that I wished fervently to find an example of my very first motorcycle, a 1964 Bridgestone 50. I'd written about this recently ("First imprint," Leanings, November, 2006), which brought distant memories of the zippy little two-stroke to the fore.

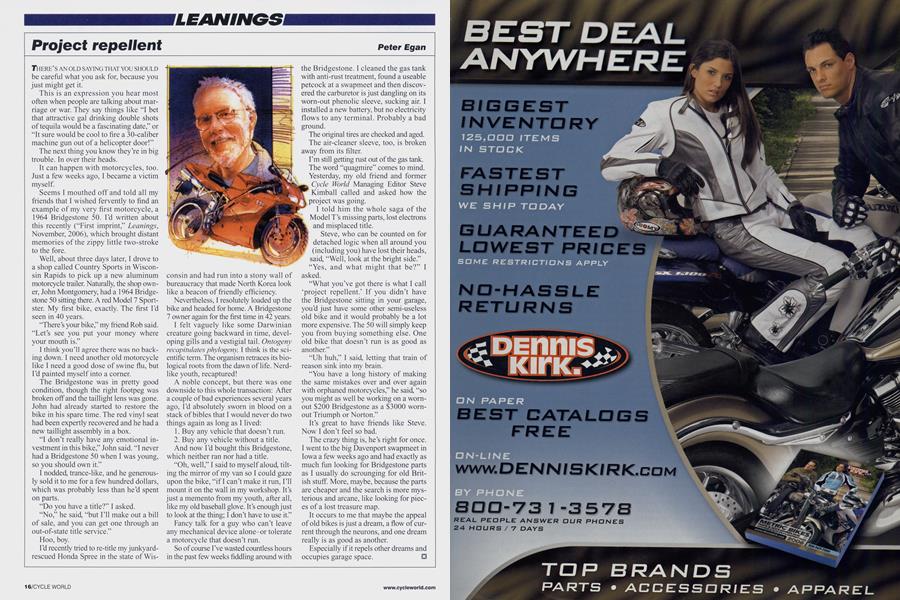

Well, about three days later, I drove to a shop called Country Sports in Wiscon sin Rapids to pick up a new aluminum motorcycle trailer. Naturally, the shop own er, John Montgomery, had a 1964 Bridge stone 50 sitting there. A red Model 7 Sport ster. My first bike, exactly. The first I'd seen in 40 years.

"There's your bike~' my friend Rob said. "Let's see you put your money where your mouth is."

I think you'll agree there was no back ing down. I need another old motorcycle like I need a good dose of swine flu, but I'd painted myself into a corner.

The Bridgestone was in pretty good condition, though the right footpeg was broken off and the taillight lens was gone. John had already started to restore the bike in his spare time. The red vinyl seat had been expertly recovered and he had a new taillight assembly in a box.

"I don't really have any emotional in vestment in this bike," John said. "I never had a Bridgestone 50 when I was young, so you should own it."

I nodded, trance-like, and he generous ly sold it to me for a few hundred dollars, which was probably less than he'd spent on parts.

"Do you have a title?" I asked.

"No," he said, "but I'll make out a bill of sale, and you can get one through an out-of-state title service."

Hoo, boy.

I'd recently tried to re-title my junkyard rescued Honda Spree in the state of Wis

consin and had run into a stony wall of bureaucracy that made North Korea look like a beacon of friendly efficiency.

Nevertheless, I resolutely loaded up the bike and headed for home. A Bridgestone 7 owner again for the first time in 42 years.

I felt vaguely like some Darwinian creature going backward in time, devel oping gills and a vestigial tail. Ontogeny recapitulates phylogenv, I think is the sci entific term. The organism retraces its bio logical roots from the dawn of life. Nerdlike youth, recaptured!

A noble concept, but there was one downside to this whole transaction: After a couple of bad experiences several years ago, I'd absolutely sworn in blood on a stack of bibles that I would never do two things again as long as I lived: 1. Buy any vehicle that doesn't run. 2. Buy any vehicle without a title. And now I'd bought this Bridgestone, which neither ran nor had a title. "Oh, well," I said to myself aloud, tilt ing the mirror of my van so I could gaze upon the bike, "if I can't make it run, I'll mount it on the wall in my workshop. It's just a memento from my youth, after all, like my old baseball glove. It's enough just to look at the thing; I don't have to use it."

Fancy talk for a guy who can't leave any mechanical device alone-or tolerate a motorcycle that doesn't run.

So of course I've wasted countless hours in the past few weeks fiddling around with

the Bridgestone. I cleaned the gas tank with anti-rust treatment, found a useable petcock at a swapmeet and then discov ered the carburetor is just dangling on its worn-out phenolic sleeve, sucking air. I installed a new battery, but no electricity flows to any terminal. Probably a bad ground.

The original tires are checked and aged. The air-cleaner sleeve, too, is broken away from its filter. I'm still getting rust out of the gas tank. The word "quagmire" comes to mind. Yesterday, my old friend and former Cycle World Managing Editor Steve Kimball called and asked how the project was going.

I told him the whole saga of the Model T's missing parts, lost electrons and misplaced title. Steve, who can be counted on for detached logic when all around you (including you) have lost their heads, f said, "Well, look at the bright side." "Yes, and what might that be?" I asked.

"What you've got there is what I call `project repellent.' If you didn't have the Bridgestone sitting in your garage, you'd just have some other semi-useless old bike and it would probably be a lot more expensive. The 50 will simp'y keep you from buying something else. One old bike that doesn't run is as good as another."

"Uh huh," I said, letting that train of reason sink into my brain. "You have a long history of making the same mistakes over and over again with orphaned motorcycles," he said, "so you might as well be working on a wornout $200 Bridgestone as a $3000 wornout Triumph or Norton."

It's great to have friends like Steve. Now I don't feel so bad.

The crazy thing is, he's right for once. I went to the big Davenport swapmeet in Iowa a few weeks ago and had exactly as much fun looking for Bridgestone parts as I usually do scrounging for old Brit ish stuff. More, maybe, because the parts are cheaper and the search is more mys terious and arcane, like looking for piec es of a lost treasure map.

It occurs to me that maybe the appeal of old bikes is just a dream, a flow of cur rent through the neurons, and one dream really is as good as another.

Especially if it repels other dreams and occupies garage space.