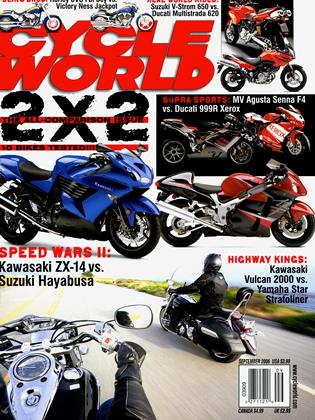

Wars of the Succession

RACE WATCH

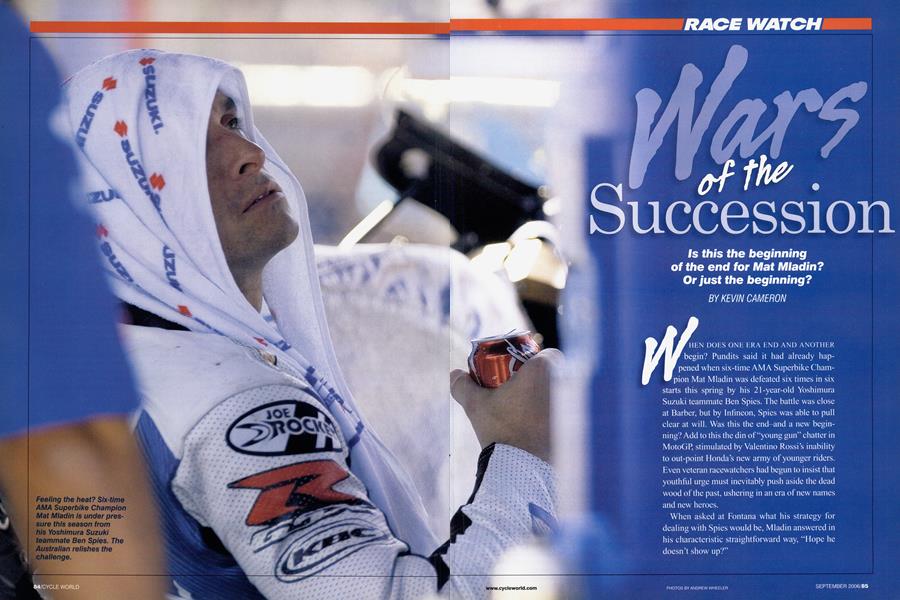

Is this the beginning of the end for Mat Mladin? Or just the beginning?

KEVIN CAMERON

WHEN DOES ONE ERA END AND ANOTHER

begin? Pundits said it had already happened when six-time AMA Superbike Champion Mat Mladin was defeated six times in six starts this spring by his 21-year-old Yoshimura Suzuki teammate Ben Spies. The battle was close at Barber, but by Infineon, Spies was able to pull clear at will. Was this the end-and a new beginning? Add to this the din of “young gun” chatter in MotoGP, stimulated by Valentino Rossi’s inability to out-point Honda’s new army of younger riders. Even veteran racewatchers had begun to insist that youthful urge must inevitably push aside the dead wood of the past, ushering in an era of new names and new heroes.

When asked at Fontana what his strategy for dealing with Spies would be, Mladin answered in his characteristic straightforward way, “Hope he doesn’t show up?”

Oops. At super-fast Road America, Mladin, brushing aside poor starts, repeatedly lowered the lap record as he caught, passed and disposed of Spies in both 100kilometer AMA Superbike races. At Mugello, well-armed veterans Rossi and Loris Capirossi confounded the youth army to finish 1-2. These wins underscore the fact that winning races is a result of what you know, not of hormonal juiciness.

In hope of learning the background of this drama, I went to Road America to talk with Mladin, Spies and the professionals they work with.

My first conversation was with Kevin Schwantz, Suzuki’s 1993 500cc GP champion, who is now an advisor and coach to Suzuki’s riders. Clearly enthusiastic about Spies’ progress, he described his shift from focusing on achieving the perfect lap to a practical appreciation of the value of working hardest in the second half of the racewhere the checkered flag is.

In 2003 and ’04,

Spies used many more tires than did his teammates in trying to achieve his perfect lap.

Schwantz and Spies’ crew chief Tom Houseworth worked to persuade him that he must learn to get the best from real-world tires that are past their peak. Schwantz added that too much

focus on perfection slows a rider’s recovery from a mistake. Instead of “Now everything’s ruined!” the rider gets back up to speed and keeps focused.

Spies has also changed his attitude toward practice. With a young man’s confidence, he would assure his crew “I can go faster in the race,” but Schwantz would reply, “Practice is the time to do it. Otherwise, how can you plan your race? How can you get your gearing and setup right if you don’t know how fast you can go?” Now, Spies uses practice like a pro, making long runs and studying the behavior of tires as they age.

I spoke with Spies in the “office” of one of the Yosh trailers. Pulling a plastic

chair over, he put his feet up on it and flung his arms out on the back of the upholstery-the very picture of royal ease. He wears his cap backward and sometimes smoothes it to make it conform to his forehead. He took charge of the conversation, speaking steadily and rapidly in a monotone, often referring to himself as “we.”

When I asked about his shift from the perfect lap to setting up for the second half of races, he acknowledged he had previously gone through a lot of tires (Dunlop men said that while Mladin typically practiced 30 kilometers on a tire, Ben averaged only 18) but had changed that in 2005.

“Last year, the bike was set up real good,” Spies continued “and we probably could have won some races on it. But I couldn’t feel what it was doing-I didn’t have confidence. Now, we’ve fixed that.”

Earlier, I had talked with Speed television commentator Greg White who said “Look at their front tires. Miguel’s is shagged. Mat’s is absolutely shagged. But Ben's is good. So he really must have learned something about the front (end).”

Part of every rider’s education is the realization that he can win. With that comes the conviction that now, he must do so, something many-time 500cc World Champion Mick Doohan has spoken of. Spies said, “Before, I’d get away fourth or fifth and plan to get past those guys to get to the front. Now I plan on being first into Turn 1.”

He also contrasted his and Mladin’s styles in bike setup. “Mat puts his bike on soft tires and plans to get away early, try to build up a cushion. The way I set my bike up now, qualifying tires don’t help much. We set up for the second half of the race and race to the flag.” Houseworth has the reputation of being able to communicate well with younger riders. He said

that their team now functions well, with everyone knowing job. “If you can’t work that way, it doesn’t matter how many people you put on-six, eight—it doesn’t help,” said Houseworth. Spies summed up his current outlook by saying, “What I’ve been doing is riding Mat’s race in the places where I didn’t have anything on him and riding my own race in the places where I was strong. It’s been working.”

I had a Friday appointment with Mladin. We went into Suzuki’s hospitality area and sat down.

“I’d love to be winning races when I’m 50 years old, but it ain’t gonna happen,” he said. “And that’s the way it’s been for millions of years. That’s life.”

Earlier, I had talked with Jim Allen of Dunlop, who had said, “Mat never, but never, gives any excuses. Mat’s bike was jumping between third and fourth gears at Barber, but it never showed up in the media. He just never mentioned it.” Mladin continued, “Right now, it’s a privilege to be riding behind someone who can really ride a motorbike. That hasn’t happened very often in the last few years. But if you don’t have anybody kicking your ass, you stop learning. That can make you complacent. Now, I’m learning again. If someone’s beating you on the same motorbike, you know he’s riding better than you.”

I recited to him what everyone knows: You have businesses, you have a family, you have your own racing team, you have a lot on your mind. He leaned back and said, “What you see here is the new Mat Mladin-someone who has quite a different attitude to life than the old Mat. This is a game. That’s what it is. Twice a weekend, a dozen times a year, I get to have this adrenaline rush. But there is another life than this.”

Why a new Mat Mladin? He seemed to be telling me what so many parents learn-that children are the truest mirror of the self. Mladin and wife Janine have a daughter, Emily, and another child on the way.

“I tingle at the thought of winning races again,” he said. “I’ve won a lot of races, but when it’s all done, what is it if you didn’t learn anything? Now, I’m learning something again, and there’s a lot to learn. The only person whose behavior you can control is yourself.

“I really took on too much,” he added, “and now I’ve begun to take measures to correct that-sold a business that I couldn’t give my mind to. I’m not done here.”

This echoed what the Dunlop men had said earlier: “Don’t count Mat Mladin out-ever. He’s not finished with this sport.”

After a moment’s thought, Mladin said.

almost disbelievingly, “I won my first championship before Ben was born. I’ve been riding motorcycles for 30 years (he is 33). That’s got to tell you something.”

Then we talked briefly about Mladin’s new airplane-a 1200-horsepower, Swissmade Pilatus PC-12 turboprop in which he and his family flew into Sheboygan airport.

In Friday qualifying, the two Suzuki teammates traded times but Spies in the last moments ran a 2:12.199—his fourth (provisional) pole in a row. In the following press briefing, he said, “That was a pure race setup,” adding that he hoped for good weather Saturday so he could run a soft tire. “I’m a little lighter, a little more aerodynamic, and that gives me a 3-4mph top-speed advantage. If I just ride my own race and I have that top-speed advantage, that should do it right there. We should do mid-12s the whole race.”

As in our earlier meeting, he spoke in a rapid, coherent monotone and said nothing extra. He clearly knows it is more impressive to say little than to babble.

It was interesting to watch the top bikes on the course. The Hondas of Miguel Duhamel and Jake Zemke “back in” on many corners-the rear-end sliding out caused by drag force from a not-quiteperfect slipper clutch. By comparison, the Suzukis look better planted, better worked out. Yet Mladin was clearly pushing hard, weaving at the rear during braking in Ben Bostrom style, showing short oscillations on direction changes and revealing occasional rear tire grip loss.

In Saturday qualifying, with just two minutes remaining in the session, Mladin went 2:12.238, then a 2:11.970 for pole position. Hmmm!

Every conversation this weekend in cluded the subject of traction control, whose forbidden status was underlined in a May 31 AMA bulletin. Yet traction control can take many forms, operating as a series of levels. When the rear wheel's acceleration rises too high, the ECU can retard the ignition timing, thereby reduc ing engine torque, allowing the rear tire to hook up again. If even deeper torque reduction is needed, the fuel mixture can be leaned out. Only for the largest torque reductions would the ignition be inter rupted, causing the telltale stuttering sound that everyone has been talking about.

When the AMA threatened to impound one bike per event unless that sound was heard no more, we can assume the teams simply re-programmed their ECUs to use only ignition retard and fuel lean-out, and riders had to take care of the rest. The re sult is a shallower but still useful torque control that cannot be externally detect ed. Mandating a post-race "software dump" would achieve nothing simply be cause such programs can be self-erasing. Saturday's 100-kilometer Superbike race initially looked to be a continuation of

Spies’ string of successes. Fulfilling his own expectation, he quickly led, reeling off the predicted mid-12 lap times. Mladin, with an undistinguished start, took six laps to get into second, overcoming Duhamel who had briefly closed on Spies. Could this be the Mladin of old, whose advance to the front has seemed as inevitable as sunrise? Pressure was visible everywhere: from Duhamel as corner-exit bobbles, from Spies as comer-entry weave.

A first attempt by Mladin turned into the classic criss-cross, as Spies came back under a running-wide Mladin to lead again.

But the juggernaut was coming. On lap seven, Mladin led, and he and Spies pulled clear of Duhamel by a second-and-a-half.

And now the decider: A big exit wobble by Spies revealed the state of his tire.

By lap eight, Mladin was lapping in the mid-12s, leading by .6 of a second, and the order was Mladin, Spies, Duhamel, Zemke, then the two Ducatis of Neil Hodgson and Ben Bostrom. As Mladin set out 12.3, 12.3, 12.6 laps, the condition of Spies’ tire forced him into the 13s. Spies was clearly scanning his cards intensely now, seeking a play that would get the best from his injured tire. Mladin’s lead of 1.25 seconds now shrank to less than a second as Spies shot back with a 12.3 then a 12.1. This man has resources, too! As Spies dipped to a sensational 2:11.9, Mladin’s lead shrank to .275 of a second. Sliding, wobbling, concentrating intensely, the two were now 10 or more seconds clear of the Hondas. At the end, it was Mladin by .148 of a second, and the two men shook hands on the cool-off lap. Both knew that another lap might have reversed the outcome.

Mladin was in the grip of strong emotion as he punched the air repeatedly, then pulled off the track for a burnout during which he pointed to himself with his clutch hand, nodded, then held up a finger for number one and finally pounded his stomach for variety.

It had been very, very close, and Spies had nearly retrieved his lead. What would happen next?

In the post-race briefing, Spies said, “Hats off to him. We didn’t have it today, but we’ll be back tomorrow.” He then referred to a gearing problem, saying his bike was geared right for two corners but needed “half a gear in some corners. I was struggling getting in.”

Mladin genially quipped that, “This little mongrel’s been up here on the box too much lately,” and later, “Ben does some things better than me in some places. I tried to go as hard as I could and not make too many mistakes.”

Then he mentioned the value of his test at Miller Motorsports Park a week earlier. When asked if he’d been concerned that Spies might draft past him on the long start-finish straight, he replied, “Nah, it’s not Daytona. You don’t want to be behind here.”

Overnight, changes were made. Spies’ crew was up `til midnight building up on a new chassis while Miadin's men up dated to the second-generation pressur ized-damper Showa fork that Spies has used all year. Only those crews know what other measures they took, but the meth ods they used were based on what's been learned by the group around Miadin.

Beginning years ago, during Suzuki's uncompetitive "years in the wilderness," a vital step toward recovery was the hir ing of instrumentation specialist Ammar Bazazz. Though he had no direct knowl edge of motorcycle racing, Bazazz rig orously applied the methods of physical science to the data gathered by on-board

instruments. He organized what was learned. He persuaded an initially skep tical Mladin to come to the computer and join him in trying to understand what the data was telling them. They were imme diately successful. Later, Peter Doyle-son of veteran Aus tralian tuner Neville Doyle-came to add his own experience and common sense. At an early test session, Doyle said, “Here, scoot forward just a bit while I tuck this padding behind you. Duct tape, someone?” The next block of practice was three-quarters of a second faster-almost for free. Doyle knows front-end push when he sees it. These men and their colleagues became the quickest at racing’s “invisible contest’-optimum use of practice time to achieve a fast, workable setup.

Results convinced the factory that these men could translate intensified development into races won-Mladin’s six AMA titles are hard to argue with. This method, built around Mladin’s riding and observational skills, helps him find a setup that allows him to go fast at a workable risk level. Simply trying harder-the “constipation theory of racing’-increases risk by eroding safety margins. As Yoshimura team manager Don Sakakura said at the end of the weekend, “Mat is always thinking, and he has ideas about every part on the motorcycle and what it can do.”

Sunday's Superbike grid came to the line. Mladin's start was a disaster, more than 10 places out of the lead. Spies led, turning low 12s. Duhamel, second, man aged a sensational, wobbling 2:11.988. Miadin advanced. Just as he'd cut Spies' advantage to five seconds, the red flag came out; Matt Lynn's engine had ex pired in heavy smoke. Where there's smoke, there's oil. At the restart, Mladin got away sixth, with two Ducatis and two Hondas be tween him and Spies. Now Mladin ran a series of 2:11 laps-among them the track record of 2:1 1.208-that carried him for ward like a natural force. Both riders slid and wobbled, but this was no grudge match. They were riding to finish, as pro fessionals always do. Miadin eased past Spies in Turn 11 on lap 10, then pulled clear to win by nearly six seconds. Now the shoe was on the other foot. In victory circle, Miadin kissed Emily, held out to him by wife Janine. Family is important, and it's not a game.

In the pressroom, Spies said, “The changes (made to the bike) were good. We had a couple of handling issues. Gotta thank my guys-they stayed up ’til midnight building me another bike. But after the second start, something was amiss. I tried to hang with Mat but there was no way.”

Mladin felt he’d ridden better the whole weekend, commenting, “It doesn't hurt the confidence.” He added that he’s adapted and moved on.

Asked about his poor starts, he replied, “I’ve got a test coming up at Ohio, and I’ve got 20 spare clutches.” He and his merry men will find something.

These had been sensational races between two equally motivated and highly skilled riders, backed by experienced crews using similar effective methods. Neither man is defeated. Both will bring fresh strengths and insights to the races coming up. It looks like there will be some long afternoons. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

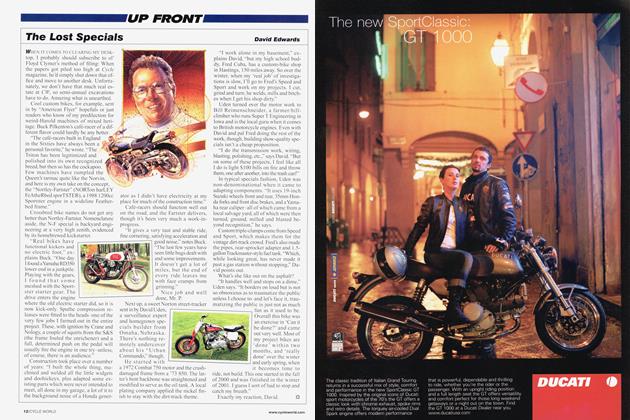

Up Front

Up FrontThe Lost Specials

September 2006 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsDangerous Liaisons

September 2006 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Mechanization of Slip-Grip Thrills

September 2006 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2006 -

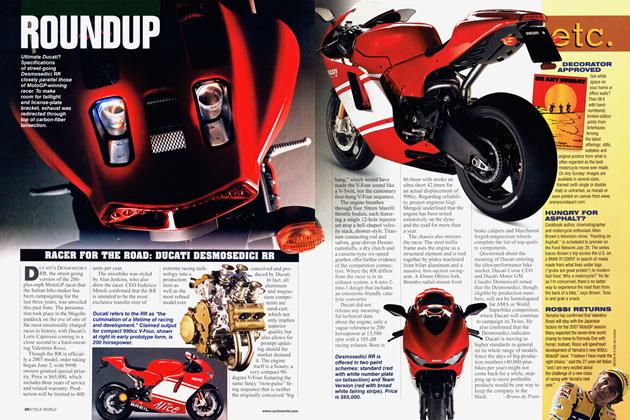

Roundup

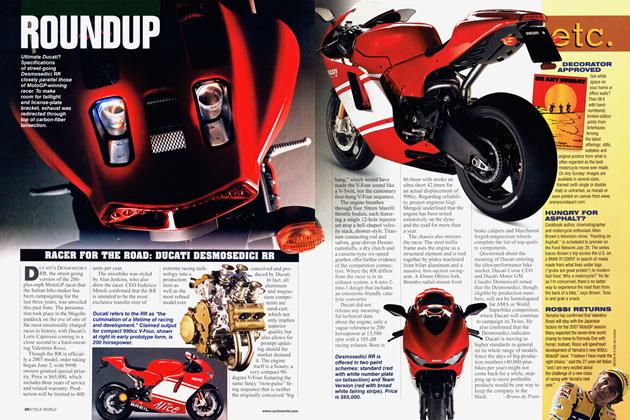

RoundupRacer For the Road: Ducati Desmosedici Rr

September 2006 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

September 2006