SERVICE

Watt’s the answer

PAUL DEAN

Q I want to increase the distance I can see when riding at night but do not necessarily want to add a light bar. My local Honda dealer says that increasing the wattage of the headlight bulb will drain the battery but that adding a light bar will not. Watt’s watt with that? Are there problems with using more-powerful headlamps or lights? Loren Stephenson Sand Springs, Oklahoma

A No, the problem is with your dealer, who evidently understands less about electricity than Ben Franklin did before flying his kite. The addition of any electrical component-a light bar, an electric vest, a sound system or anything that requires voltage to operate-increases the current draw on the electrical system. Likewise, so does replacing an existing headlight with one that has a higher wattage rating.

It’s all a matter of simple arithmetic. Electrical components are rated in wattage, a figure calculated by multiplying the voltage of the electrical system by the amperage requirements of the component in question. A typical headlight, for example, has a 55/60W bulb; the low beam draws 55 watts, the high beam 60. Divide the wattage of the high beam (60) by the system’s voltage (12) and you get 5, the number of amperes used by the high beam.

You didn’t mention which Honda model you ride, so for the sake of discussion, let’s assume it’s a VTX1800 with a stock 5 5/60W headlight bulb. If, for example, you were to install one of the 80/80W bulbs available in the aftermarket, you would increase the high-beam wattage by 20, which would draw 1.7 (20=12=1.7) more amps for a total of 6.7 amps. The average light bar, meanwhile, has two bulbs, each usually rated at no more than 35 watts for a total of 70. If you then add the stock headlight’s 60 watts on high beam, you end up with 130 watts (10.8 amps) of lighting.

So do the math: With a light bar, you end up with a two-thirds greater current draw than with a high-output headlight bulb. Depending upon the alternator output of your bike, the charging system might not be able to keep the battery charged at cruising speeds when the light bar and stock high beam are illuminated, but the added wattage of the aftermarket headlight bulb would present no charging problems.

Besides, most light-bar reflectors are not configured to project light way down the road; they instead produce .wide-beam illumination that brightens the area just ahead. An 80-watt highbeam headlight, however, would fire a brighter and narrower beam much farther down the road.

As I said, your dealer is electrically challenged. Install the headlight bulb.

Expansion plans

QI have a technical question that has plagued me for years. I’ve always been curious as to exactly what “expansion chamber” exhausts do and why they are used exclusively on twostroke engines. I’m guessing it has something to do with standing waves inside the pipe that perhaps create a lowpressure area at the mouth of the exhaust to help evacuate the combustion chamber. If this is the case, wouldn’t expansion chambers also be useful on fourstrokes? It would really mean a lot to me if you could explain what is taking place inside the pipe and why.

Wayne Schlickeisen Gatesville, Texas

A The theory, design and tuning of expansion chambers is a subject complex enough to fill entire books, so I won’t be able to provide a detailed explanation in this limited space. But you’re on the right track with your thinking, although expansion chambers don’t just create a low-pressure condition at the exhaust port to help evacuate spent gases from the combustion chamber; at the appropriate moment, they also create a high pressure there that helps prevent the incoming intake charge from being sucked out through the exhaust before it can be burned.

On a four-stroke, the valves are operated mechanically, so their opening and closing points do not have to be symmetrical. In other words, no matter at what point before or after Top Dead Center (TDC) a four-stroke valve opens, it can close at any other piston location deemed necessary by the engine’s designer or tuner. But on a two-stroke, port openings and closings are controlled by the movement of the piston, which means they are symmetrical; if an exhaust port opens at, say, 85 degrees After TDC as the piston is on its way down, it also must close at 85 degrees Before TDC as the piston is on its way up. Therein lies one of the major challenges of two-stroke design: The power-producing events in an engine do not behave in a manner that can be optimized with symmetrical port timing. This evenness of timing might possibly work acceptably within one narrow band of engine speed, but elsewhere in the rpm range, it tends to create low pressure where high pressure is needed and vice versa. That’s why four-strokes have asymmetrical timing.

Tool Time

Nothing complicated about cutting a hole in the end of a handgrip, is there? Just grab a knife or a razor blade and hack away until enough of the end has been carved out to let the grip fit over a bar-end weight, a bar-end mirror or a mount for an off-road brush guard. Cutting rubber can be an imprecise art, however, so the finished hole might not be sufficiently round, or enough of the end could still remain on the right-side grip to drag on the weight/mirror/mount and cause the throttle to hang up; if so, you then have to pry the grip back off and trim it some more.

You could have cut a cleaner hole on the first try with the Grip-End Cutter from Motion Pro (part no. 08-0335; www.motionpro.com). Designed for grips that fit 7/»-inch bars, this is a three-piece tool consisting of two knife-edged cutting cylinders (a 7/s-inch cutter for the left handlebar and a 1-incher for the throttle sleeve on the right), each of which threads into a long steel handle. To cut the hole, you screw the appropriate cutter onto the handle, insert the tool down into the grip and, with the closed end of the grip resting on a piece of wood, give the top of the handle a couple of whacks with a hammer. The tool cuts so cleanly that the grip winds up looking like it was originally manufactured with a hole in the end. For some people, buying a $23 tool for a one-time holecutting job doesn’t make sense; but for riders who make frequent grip changes on bikes that use bar-end-mounted equipment, this is a useful toolbox addition.

Evidently, I awakened the innovator in quite a few readers when I wrote about the Magnetic Finger Glove in February’s “Tool Time.” I’ve gotten responses suggesting all kinds of methods of inserting nuts and bolts into tight spaces-grease, hot glue, duct tape, museum wax, silly putty, you name it. One of the more fascinating has come from J.H. Crawford, owner of a small aircraft-maintenance business (Crawford Motor Co.; 901/465-6044) in Williston, Tennessee. Years ago, Crawford invented the Gotcha, a clever little tool that looks like an elaborate pair of tweezers with two sets of stubby half-circle prongs on the end. One set of prongs is angled at 90 degrees to the tweezer blades, the other aims straight out on the blades’ ends. A small sleeve on the blades can be slid toward the prongs to force the spring-loaded blades together, or left at the base so the blades can spread apart. To use the Gotcha, you squeeze the blades together, insert one of the prong sets inside a nut and then release the blades; the spring tension of the blades holds the nut in place. To hold a bolt, you spread the blades far enough apart to fit across opposing corners of the hex, then push the slider up until the blades are forced together firmly enough to securely hold the fastener; this outside-grip method also

will hold a nut. You can use either the 90-degree prongs or the straight ones, depending upon the available access room at the point of installation. And space permitting, the tool also allows you to turn the nut or bolt enough to start it on the threads. Best of all, the Gotcha's list price is just $7.50.

Paul Dean

On two-strokes, the intake ports cope

with this symmetry either through use of reed valves (one-way "gates" that allow fuel mixture to be sucked into the intake port but not get pushed back out when the piston reverses direction) or with rotary valves (crank-driven rotating discs that can provide asymmetrical intake timing). But such devices are not feasible for exhaust ports, due mainly to the intense heat of the burning gases exiting the combustion chamber. Some two-strokes employ “power valves,” which vary the height of the exhaust port according to engine rpm; but while these effectively make the port shorter at lower rpm for better torque and taller at higher revs for greater power, the timing of those ports still remains symmetrical.

Which brings us to expansion chambers, which use the natural pressure waves of the exhaust to help overcome the effects of symmetrical port timing. Expansion chambers consist of five parts: a head pipe; a divergent cone; a center section; a convergent cone; and a tailpipe or “stinger.” As the exhaust waves travel along the head pipe, they undergo a sudden expansion when they reach the divergent cone. This creates a low-pressure condition at the port that helps “pull” the burning gases out of the combustion chamber. The waves then move across the center section and hit the convergent cone, which reflects a > high-pressure wave back through the pipe to the exhaust port, pushing back into the combustion chamber any fresh mixture that may have been drawn out at the tail end of the exhaust cycle.

Feedback Loop

To David Ansell, who has a problem with one cylinder cutting out on his '85 Yamaha Virago (“One-lung Virago,’’ May, 2006):

I had identical problems on my beloved and otherwise reliable ’86 XV700, and the problem was intermittent. When a condition is intermittent, mechanics can’t duplicate it, so I can’t be too hard on them for trying different guesswork fixes. As the cut-out increased in frequency over time, I had more chances to search for the problem. It turned out to be one bad wire in the section of the wiring harness that goes around the steering head and into the headlight. I diagnosed it using the trial-and-error method of manipulating different parts of the harness during cut-outs. Sure enough, by pushing a certain segment of the harness in a particular direction, power could reliably be restored. From there it was a simple matter of picking out the most likely culprits from the Virago service manual’s wiring diagram, tearing open the harness and moving individual wires to find the offending semi-broken wire-a power feed to the front coil.

Charles H. Bonnett Narberth, Pennsylvania

Thank you very much, Charles. If Mr. Ansell has not yet found the source of his Virago’s problem,

I’m sure he’ll soon be wiggling the wires behind his headlight in the hope of getting his Virago to run on both cylinders.

The timing of these events is critical, and it is controlled by every dimension of the expansion chamber-the length and diameter of the head pipe, the center section and the stinger, as well as the angle and length of the divergent and convergent cones. Figuring the right combination of those dimensions is what makes expansion-chamber design such a dark art, for it changes with every difference in engine design and tuning.

Because four-strokes have asymmetrical valve timing (and fire only half as often as a two-stroke at any given rpm), they present a different exhaust-system problem that is not best solved with an expansion chamber. Nevertheless, they do respond favorably to exhaust tuning that capitalizes on the behavior of sound waves; and as with expansion chambers, this tuning is accomplished through dimensional changes to the components in the exhaust system.

Taking a powder

Q I have a 1998 Honda VFR750F. I want to have the wheels powdercoated, but I’m concerned that the high temperatures involved will damage them. Will the 400 degrees it takes to melt the

powdercoat have any ill effects on the aluminum wheels? Tobin Baker

Waynesboro, Pennsylvania

Aí wish I had a definitive answer to that question, but I don’t. And neither do most of the people in the powdercoating business, primarily because there are so many variables to consider. Aluminum does not reach the melting point until around 1200 degrees Fahrenheit, so there’s no fear of the wheels turning into molten puddles while in the oven. But depending upon their alloy and method of manufacture (cast or forged), aluminum wheels can begin to anneal (lose some of their rigidity) at just over 500 degrees, and the aging process is accelerated (which can lead to loss of strength and shortening of fatigue life) at even lower temperatures. In some cases, increased aging (called “overaging”) can occur at temperatures as low as 325 degrees.

Candid Cameron

Q I’ve watched the Evinrude/Bombardier infomercial for their new E-Tec outboards in which they claim their two-strokes not only meet all EPA regs but have significantly lower emissions than their four-stroke competition. They also claim superior fuel economy and low-end torque. If their claims are even partly true, could this be the rebirth of the two-stroke streetbike? ECM’s are now cheap and readily available, and high-pressure fuel-injection is only a license fee away. So when can I put my deposit down on a new H1 or RD400? Joel Greene

Dunedin, Florida

A E-Tec appears to be an excellent solution but it is still a minority one. Which means that as emissions standards tighten, those using E-Tec must gamble on improvements to it being no more expensive than conversion to four-stroke and getting on the prepaid four-stroke emissions bandwagon. What I mean by “bandwagon” is that automakers pay the cost of four-stroke emissions solutions; after that, others can buy those solutions at comparatively low cost because they have been put into mass production.

E-Tec can operate to higher rpm than did its predecessor, Ficht injection, or it can inject its fuel that much faster, thereby allowing more time for fuel-droplet evaporation. Thus, while so far there is no 12,000-rpm direct injection for two-strokes, it would be practical to again make something like a Yamaha RD400, but offering low emissions and excellent fuel economy. I think it would be expecting a lot, however, for any motorcycle manufacturer, having once paid to convert to four-stroke technology, to go back the other way. If our current DFI systems had come along 20 years sooner, the story might have been different. -Kevin Cameron

On the other hand, most painted aluminum wheels are powdercoated at the factory, so their manufacturers apparently believe the alloys they use are safe to endure the baking process. There also are powdercoatings on the market that require only about 275 degrees to cure, well within the range of safe temperatures. The resultant finish with these low-temperature coatings sometimes has a very slight “orange peel” texture, but for use on wheels, that would not seem to be a significant deterrent.

EFI economics

Q In the May Service section, you talked about the difference between carburetors and fuel-injection at high altitudes. What are the pros and cons of the two systems, and how difficult/expensive would it be to switch from one to the other? I’m considering the purchase of a used Honda Valkyrie, which is powered by a retuned and carbureted version of a fuel-injected Gold Wing engine. Would it be worth the effort and cost to mount an injection system from a Gold Wing? Randy Hawes

Grand Prairie, Texas

A Answering your last question first, no, it would not be worth the time, effort and expense to convert your Valkyrie to fuel-injection. The Valkyrie’s engine is based on the 1520cc Gold Wing motor, which never was fuel-injected; it was equipped with two 36mm carbs as opposed to the Valkyrie’s six 28mm instruments. The six-cylinder Wing didn’t get EFI until it grew to the current 1832cc version in 2001. Those two engine designs are different enough that the 1800’s injection system would not bolt up to the 1500’s engine. Chief among the design differences between the two engines is that the cylinder heads on the Valkyrie do not have provisions for injector nozzles.

Burn, baby, burn

Q I have a 2003 Yamaha YZF-R6 that makes a very annoying ticking sound in second gear only. It all started during a prolonged burnout when I shifted from first to second. I took the bike to a dealership that thinks they know what the problem is, but they don’t know if my extended warranty will cover the cost of repairs until they take it apart. The problem doesn’t seem to affect the bike’s performance, so I’m wondering if I am causing more damage by continuing to ride it or if I (or Yamaha) should dish out the money to get it fixed. Andy Erickson ~ Hillsboro, Wisconsin

A l know nothing about the terms of your extended warranty, but if the ëa1er is~ware that the second-gear tick-~ ing noise in your, l~.6 is the result of ai~ upshift duripg a long burnout, he is very likely to reject the claim. Most warranties, original or extended, give the insurer the right to deny a claim if the failure has been brought about by abuse. And shifting gears during a burnout is abuse by any definition of the word. The burnout itself isn’t exactly TLC, either.

As far as the ticking noise is concerned, it’s probably being caused by a chip on one of the gear teeth. Your bumout-with-upshift may have been what chipped the tooth, or perhaps previous indiscretions (you don’t expect me to believe that this was the first time you had done such a thing-or even worse) weakened the hardened surface of the tooth, which finally gave way during your latest incident.

Whatever its cause, the condition will only worsen with further use. Right now, the cost of repairs could involve just two gears and the labor (R&R the engine, split the cases, etc.) to replace them. If one of the teeth breaks off altogether and jams between two meshing gears, the damage could be much more extensive, possibly calling for replacement of the engine cases and many more transmission pieces. Regardless of who foots the bill, you or Yamaha, the problem needs to be remedied ASAP.

Arm with one leg

Q I am currently in the market for my next and probably last (according to She Who Must Be Obeyed) motorcycle. I’m drawn to adventure-style bikes and have always loved the looks of single-sided swingarms like those on the Ducati Multistrada and BMW R1200GS. I recently read the reviews of the Buell Ulysses, which has a standard swingarm, but I also find it appealing. Those three bikes fit what I am looking for in an all-around motorcycle that has a more-upright riding position; my wrists and back have grown too old for a sportbike. Other than the benefits of what appears to be maintenance ease with the single-sided swingarm, what are the pros and cons of each style? If singlesided arms are better functionally, why are they not more popular, other than cost? A According to I Who Should Be Heeded But Is Frequently Told To Buzz Off, there are no substantive advantages of single-sided swingarms over conventional arms for street use. Yes, singlesided arms allow you to remove the rear wheel more easily, which is why they were invented in the first place: to speed pit stops in endurance racing. But for road use, there is no appreciable benefit. In fact, once you get the wheel off, you find that getting it balanced is not always so simple. The wheel contains no bearings, which instead remain in the hub, so mounting it in a balancing device requires special cones not found at all motorcycle dealerships and repair shops. Plus, wheel-bearing (technically, that should be ¿«¿-bearing) service and replacement usually is more complicated and expensive than it is with a wheel that runs in a conventional swingarm.

Lee Limbaugh Eugene, Oregon

Honda and BMW began using singlesided arms on some production bikes in the 1980s, but it was Ducati that popularized the concept in 1994 with the 916. Even then, one of the main reasons Ducati chose a single-sided arm was to provide more cornering clearance. The header pipes for the 916’s under-seat exhaust could be tucked in more tightly behind the rear frame downtube, with the pipes’ upward bend occupying space traditionally taken up by the front of a conventional arm. The quick-change feature was nice, of course, and having the right side of the wheel fully exposed contributed to the 916’s I-mean-business appearance. But although the 916 and its 996/998 successors continued to use that same basic design, there is no evidence that any part of those bikes’ superb handling was owed to their swingarms. In fact, even in roadracing classes that permit any kind of swingarm, most motorcycles still use conventional arms. □

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your beloved ride? Can’t seem to find workable solutions in your area? Or are you eager to learn about a certain aspect of motorcycle design and technology? Maybe we can help.

If you think we can, either: 1) Mail a written inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service,

1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663; 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/6310651; 3) e-mail it to CW1Dean@aol.com; or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com, click on the “Contact Us” button, select “CW Service” and enter your question. Don’t write a 10page essay, but if you’re looking for help in solving a problem, do include enough information to permit a reasonable diagnosis. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we cannot guarantee a reply to every question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

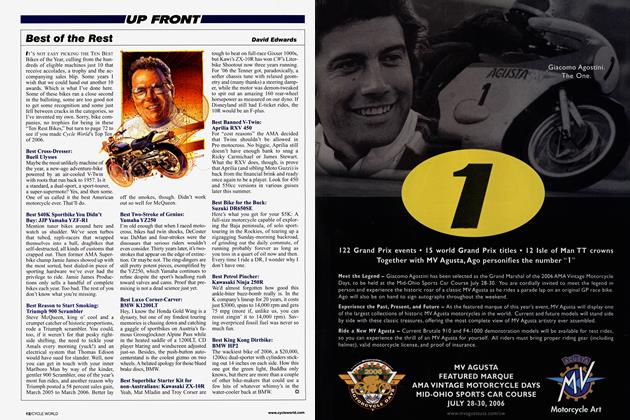

Up FrontBest of the Rest

July 2006 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Fine Art of Riding Your Own Bike

July 2006 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCRossi's Woe

July 2006 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2006 -

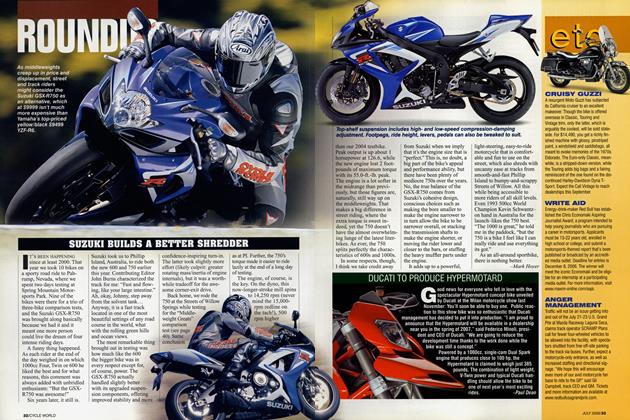

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki Builds A Better Shredder

July 2006 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

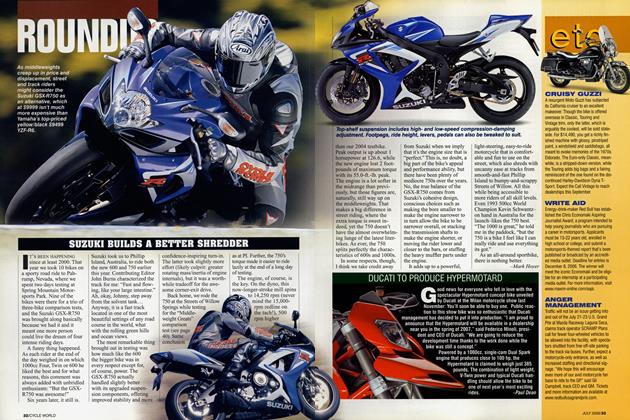

RoundupDucati To Produce Hypermotard

July 2006 By Paul Dean