STAFF STUFF

BACK IN THE 1970s, when the AMA’s Grand National series mandated production-based 250cc Singles for short-track races, Harley-Davidson certified its Italian-made two-stroke motocross engine and sold it—to those who knew where and how to get one—along with a list of suitable frames, suspension and so forth.

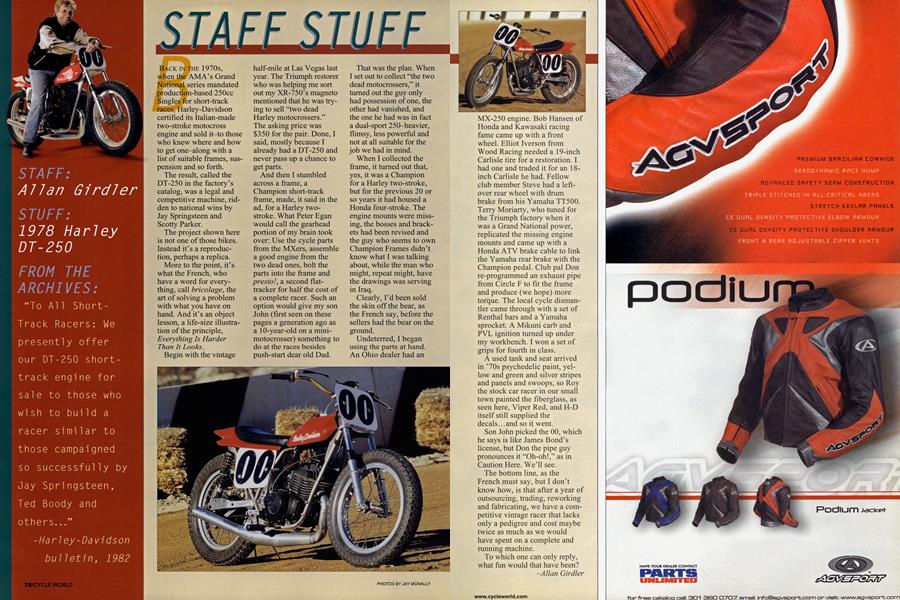

The result, called the DT-250 in the factory’s catalog, was a legal and competitive machine, ridden to national wins by Jay Springsteen and Scotty Parker.

The project shown here is not one of those bikes. Instead it’s a reproduction, perhaps a replica.

More to the point, it’s what the French, who have a word for everything, call bricolage, the art of solving a problem with what you have on hand. And it’s an object lesson, a life-size illustration of the principle, Everything Is Harder Than It Looks.

Begin with the vintage half-mile at Las Vegas last year. The Triumph restorer who was helping me sort out my XR-750’s magneto mentioned that he was trying to sell “two dead Harley motocrossers.”

The asking price was $350 for the pair. Done, I said, mostly because I already had a DT-250 and never pass up a chance to get parts.

And then I stumbled across a frame, a Champion short-track frame, made, it said in the ad, for a Harley twostroke. What Peter Egan would call the gearhead portion of my brain took over: Use the cycle parts from the MXers, assemble a good engine from the two dead ones, bolt the parts into the frame and presto!, a second flattracker for half the cost of a complete racer. Such an option would give my son John (first seen on these pages a generation ago as a 10-year-old on a minimotocrosser) something to do at the races besides push-start dear old Dad. That was the plan. When I set out to collect “the two dead motocrossers,” it turned out the guy only had possession of one, the other had vanished, and the one he had was in fact a dual-sport 250-heavier, flimsy, less powerful and not at all suitable for the job we had in mind.

When I collected the frame, it turned out that, yes, it was a Champion for a Harley two-stroke, but for the previous 20 or so years it had housed a Honda four-stroke. The engine mounts were missing, the bosses and brackets had been revised and the guy who seems to own Champion Frames didn’t know what I was talking about, while the man who might, repeat might, have the drawings was serving in Iraq.

Clearly, I’d been sold the skin off the bear, as the French say, before the sellers had the bear on the ground.

Undeterred, I began using the parts at hand.

An Ohio dealer had an MX-250 engine. Bob Hansen of Honda and Kawasaki racing fame came up with a front wheel. Elliot Iverson from Wood Racing needed a 19-inch Carlisle tire for a restoration. I had one and traded it for an 18inch Carlisle he had. Fellow club member Steve had a leftover rear wheel with drum brake from his Yamaha TT500. Terry Moriarty, who tuned for the Triumph factory when it was a Grand National power, replicated the missing engine mounts and came up with a Honda ATV brake cable to link the Y amaha rear brake with the Champion pedal. Club pal Don re-programmed an exhaust pipe from Circle F to fit the frame and produce (we hope) more torque. The local cycle dismantler came through with a set of Renthal bars and a Y amaha sprocket. A Mikuni carb and PVL ignition turned up under my workbench. I won a set of grips for fourth in class.

STAFF: Allan Gird 1er

STUFF: 1978 Harley DT-250

FROM THE ARCHIVES: “To Al 1 ShortTrack Racers: We presently offer our DT-250 shorttrack engine for sale to those who wish to build a racer similar to those campaigned so successfully by Jay Springsteen, Ted Boody and others...”

-Harley-Davidson bulletin, 1982

A used tank and seat arrived in ’70s psychedelic paint, yellow and green and silver stripes and panels and swoops, so Roy the stock car racer in our small town painted the fiberglass, as seen here, Viper Red, and H-D itself still supplied the decals...and so it went.

Son John picked the 00, which he says is like James Bond’s license, but Don the pipe guy pronounces it “Oh-oh!,” as in Caution Here. We’ll see.

The bottom line, as the French must say, but I don’t know how, is that after a year of outsourcing, trading, reworking and fabricating, we have a competitive vintage racer that lacks only a pedigree and cost maybe twice as much as we would have spent on a complete and running machine.

To which one can only reply, what fun would that have been?

Allan Girdler

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAussie Rules

March 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOn the Trail of the Mighty One

March 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTelephone Teams

March 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

March 2005 -

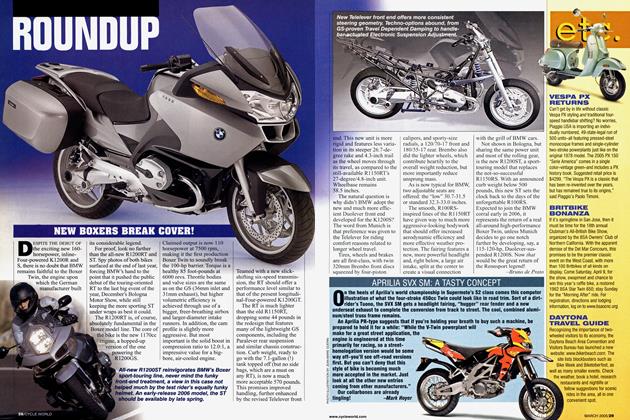

Roundup

RoundupNew Boxers Break Cover!

March 2005 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Svx Sm: A Tasty Concept

March 2005 By Mark Hoyer