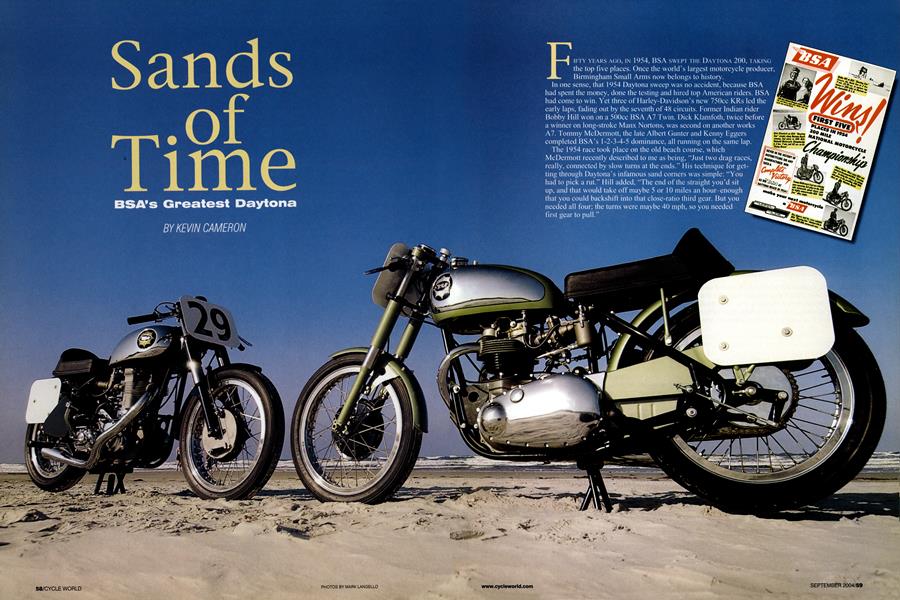

Sands of Time

BSA's Greatest Daytona

KEVIN CAMERON

FIFTY YEARS AGO, IN 1954, BSA SWEPT THE DAYTONA 200, TAKING the top five places. Once the world's largest motorcycle producer, Birmingham Small Arms now belongs to history. In one sense, that 1954 Daytona sweep was no accident, because BSA had spent the money, done the testing and hired top American riders. BSA had come to win. Yet three of Harley-Davidson's new 750cc KRs led the early laps, fading out by the seventh of 48 circuits. Former Indian rider Bobby Hill won on a 500cc BSA A7 Twin. Dick Klamfoth, twice before a winner on long-stroke Manx Nortons, was second on another works A7. Tommy McDermott, the late Albert Gunter and Kenny Eggers completed BSA's 1-2-3-4-5 dominance, all running on the same lap.

The 1954 race took place on the old beach course, which McDermott recently described to me as being, Just Iwo drag races. really, connected by slow turns at the ends. Ills technique For get ting through E)aytona's ililafliOUs sand corners was simple: You had to pick a rut." II ill added, The end of the straight you'd sit up, and that would take oil maybe 5 or 10 miles an hour enough that you could backshift into that close-ratio third gear. Rut ou needed all four; the turns were maybe 40 mph, so you needed first gear to pull."

Part roadrace, part deep-sand scramble, this event took 2 hours and 7 minutes-a long, long moto-and Hill’s race average that day was 94.24 mph. One of the early leaders, Paul Goldsmith, tried to clear oil from his goggles but only obscured them more. Unable to see, he ran off the course and literally “caught a wave.”

About clearing his goggles, Hill said, “I had a powder puff on the back of my glove, and I’d just reach up and lightly wipe it across.” Victory often resides in such small details. BSA personnel brought over eight specially built machines for this race, four A7 parallel-Twins and four 500cc Gold Star Singles. In the two previous years, BSAs had run near the front, but a post-race check of the 1953 engines showed low horsepower. At the factory, a new man, Roland Pike, was put in charge of preparing the 1954 machines. Pike, a veteran Isle of Man TT privateer with an impressive background in building reliability and performance, had been made head of BSA’s development department. Jack Amott, who formerly held the post, left over differences of outlook with BSA’s new chief engineer, Bert Hopwood. Amott prepared the BSA one-lunger on which retired GP star Wal Handley had earned a Brooklands Gold Star award for a 100-mph lap in a 1937 race. This led directly to the long line of BSA Gold Stars that would win countless events on both sides of the Atlantic in years to come. But Hopwood had been hired to make BSA’s Twins a success, as management had decided that Singles were outmoded. Triumph had gained considerable sales and competition success with its Speed Twin. Two cylinders were the wave of the future.

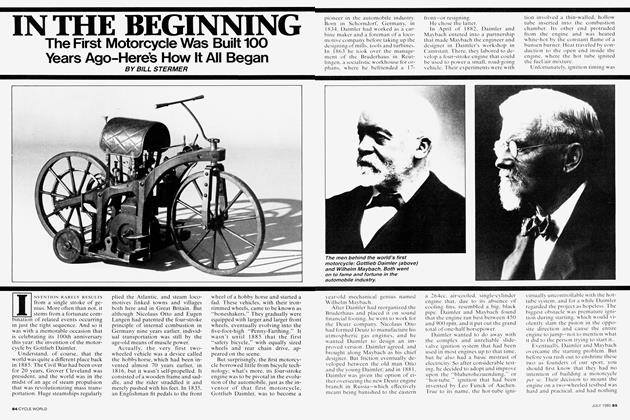

Aside from the Handley episode, BSA had held itself aloof from roadracing since 1921, when eight factory-built racers went to the Isle of Man and completely disintegrated in embarrassing ways. The company then went back to its core business-building solid, reliable transportation for the masses. This corporate history made it all the more remarkable that the company should support a Daytona adventure in far-flung Florida, yet there were solid reasons for the expedition. When WWII ended, England was broke, and its Board of Trade ordered all manufacturers to vigorously export British products.

In the U.S., motorcycles were heavy Indians and Harleys, bikes whose evolution had been slowed by competition from Henry Ford’s cheap Model T and by the Great Depression. The postwar mood wanted excitement, and sportier British motorcycles were refreshingly light, powerful and agile. British sales in the U.S. received a further boost in 1949 from the devaluation of the pound sterling-prices of Triumphs, Nortons and BSAs dropped by 25 percent almost overnight.

One result was a Daytona assault by Norton, which won on the beach from 1949 to ’52. The dohc Manx Singles had been developed to impressive reliability over many years in the TT, and could cope with the AMA’s compression-ratio limit of 8.5:1 because poor postwar British fuel had already required a deep cut in compression.

Two other big shifts were occurring. Indian, which won Daytona in 1947 and ’48, had a long tradition of racing succcss. Now the “Wigwam” was weakening because it had gambled and lost on some hasty lightweight designs meant to blunt the British invasion. Indian would cease production in 1953, and was eking out its existence as an importer of Nortons and rebadged Enfields. At the same time, Harley had responded to the Brits by designing an all-new sports machine, the K, later to become the Sportster. It featured compact unit construction and, like postwar British road bikes, a telescopic fork and hydraulically damped swingarm rear suspension. It would take time to develop this machine, even though its engine was a simple flathead with its intake and exhaust valves stems-down at the side of each cylinder. Such engines can achieve rapid combustion because of their large, turbulence-generating squish area, but cannot reach high compression ratios because of the extra volume involved in providing adequate flow to the side-mounted valves. Low compression raises the exhaust temperature, which combines with the location of the exhaust port next to the iron cylinder to make the exhaust valve difficult to cool. The result was an early tendency for exhaust valve failure. The BSA Singles and Twins, by contrast, were pushrod overhead-valve engines with high-heat-conductivity finned aluminum heads. Their exhaust ports faced forward, in the airstream, so they cooled relatively well. In all of this, you can see the makings of a controversy that has yet to be laid to rest, the limiting of ohv motors to 5()0cc while allowing the flatties an extra 25()cc. Builders and riders of British bikes saw the 500/750 displacement rule as unfair, even facilitated by undue Harley and Indian influence within the sanctioning body, the AMA. Flathead men saw the rule as a simple and appropriate compensation for the fact that it’s much harder to get air to flow' through a flattie’s contorted porting than through the straighter ports of an overhead.

Our own time has its own such argument. In Superbike, lOOOcc Twins for years raced against 750cc Fours-and at first. Twins got a weight break as well. Did unfair rules give Ducati all those world titles? Or did Bologna win by developing engines while the others planned only “bold new graphics?” Like the flathead 750 rule, this will be debated as long as anyone is left alive who cares. BSA’s A7 was modern in the sense that all British companies were following the lead of Triumph’s Edward Turner, who had in 1937 shown the advantages of a parallel-Twincompared with a Single, its shorter stroke and increased valve area give increased performance, while minimum reciprocating weight cut vibration. Also, its simple, vertically split crankcase fit into frames already in production. Hopwood’s 66.0 x 72.6mm A7 racer had a difficult childhood of broken cranks. With no center bearing, the higher it revved, the more it flexed, generating cracks at the fillet radii where crankpins merged into the flywheels. The cure was to roll the fillets, placing their surfaces in compression. Management and Hopwood wanted to send only Twins to Daytona. Pike, with abundant racing experience on Gold Stars, believed both types should go. But in testing at the MIRA high-speed oval in England, the A7s had shown a top-speed advantage over the Single. “The winning machine is the one that crosses the finishing line first,” Pike reminded Hopwood, “not the one that crosses it fastest.”

He proposed a test to make his point. One of each machine type would roll at 20 mph in first gear past a starting mark. At the mark, the two riders would open up and accelerate to the top of fourth gear. In the test, the Single pulled ahead and away, and only in top gear, near maximum speed, did the Twin begin to close. Hopwood accepted this, and equal numbers of Gold Stars and A7s went to Daytona. Pike had shown the differ ence-even today ignored by those who should know bet ter-between peak horsepower and horsepower averaged across the range of rpm actually used in competition. Pike had been impressed with the size and enthusiasm of the U.S. motorcycle market on previous visits. His depart ment developed and built the Daytona machines, running hours of high-speed track testing and dyno operation to find and eliminate failures. Twin Ama! carbs with remote floatbowls replaced the street A7's solitary Monoblock. Save for one bike, the BSAs that ate Daytona in 1954 had rigid frames-the result of Pike's determination that the beach course would reward lightness most of all. BSA succeeded because the company trusted good people to do all that racing requires. By chance, this happened just as Norton and Indian were weakening, and Harley's KR was too new to be fully reliable. Factory teams never work harder than when trying to beat privateers on the same brand. In Harley's case, the privateer was the famed Tom Sifton, a one-man R&D department who virtually defined the future of the Harley KR. His work, more than anything else, was the reason BSA's 1954 success was not repeated. KRs would win the next seven Daytonas. Ironically, Sifton tested valve springs made by engineer Tim Witham, prepared by shotpeening, a wartime development. This directs a blast of air-driven hard steel shot at metal surfaces, placing them in compression. Because cracks form only in tension, this compression allows a part to be more highly stressed for a given level of surface tension. The result is increased fatigue strength. Witham's springs overcame breakage in the KR. In 1956, BSA's West Coast distributor Hap Alzina sent some of Witham's S&W springs to Pike. These then became standard on BSA Gold Stars.

Although BSA would not win Daytona again until Dick Mann's 1971 Speedway ride on the mighty Rocket 3, Pike and the Gold Star Single would have a lasting effect on U.S. racing. Pike's development work would continue until he left the company in 1957, but the result would win roadraces, flat-tracks, scrambles, enduros and trials for many years. In England, this included virtual ownership of the Clubmans TT for production-based bikes. Among tuners who worked with all the great Singles, the Gold Star cylin der head was regarded as the best design, with the highest horsepower potential. Its relatively narrow valve angle and intake downdraft plus offset gave it a compact combustion chamber that burned quickly and with moderate heat loss. While searching for ways to find room for a larger intake valve, Pike discovered that exhaust valves and ports smaller than usual could be made to flow just as well as bigger ones. The reduced surface area of the port and shorter heat path of the valve combined to lower cylinder head temperature and extend valve life. In our own era, the late Jim Feuling made good money selling this same exhaust valve-and-port reduc tion procedure to frankly disbelieving automotive and motor cycle manufacturers. The BSA Gold Star was an engineering education for a generation of American engine tuners and engineers, despite its being eased out of production on vari ous pretexts ("We can't get generators for it anymore.. . "Anything without unit construction is obsolete...") in the early 1960s. The Gold Star has a classic look available nowhere else. The 497cc A7 Twin was expanded into the 646cc A10, and later converted to unit construction in the A50/65 series, which would run 'til BSA’s sad demise in 1973. British vertical-Twins were the orthodoxy of high-performance motorcycling for a generation, and BSA built a large percentage of them. For a short golden age, BSA’s development department kept more powerful models moving into the performancehungry U.S. market, and all was well. But nothing is forever. Beginning in the middle 1960s, a weak BSA management that valued cost savings over engineering frittered away first the company’s reputation, then its sales, and finally its existence. This June, I attended the opening of a special exhibit at the American Motorcyclist Association's museum in Pickerington, Ohio, dedicated to the achievements of those who made possible BSA’s 1954 Daytona win. Roland Pike is no longer living, but his image, leaning over a bike in the BSA development shop, wearing his faithful tweed jacket, overlooked the cluster of restored machines. In a small case are some of his original work notes and in particular, the conclusions he drew from testing a family of five research engines he built, all 350cc Singles but covering a wide range of bore/stroke ratio. Don’t think of the past as being unsophisticated because it lacked computers and automated tooling. Pike’s understanding of the internal-combustion engine was detailed and intimate, the result of a lifetime of close observation and experience. It is human ideas, not silicon brains, that map the way to high performance. BSA nibbled at the edges of what would in the latter 1960s become a huge new motorcycle boom. Again and again, small-displacement “starter bikes,” mopeds and scooters were proposed, prototyped and then either marketed improperly or canceled. The dominant idea was that big-bike sales were the only real market-don’t waste time and resources on “the little stuff.” Meanwhile, Japan was inoculating hundreds of thousands of Americans with step-through 50s and 65s, and small, sporty-looking 90 and 125cc motorbikes. Just as Alfred P. Sloan at GM had built a “stairway of models,” enticing new auto buyers to move up to fancier models, so Japan led the step-through buyer onward by easy stages to own bigger and bigger machines. Just as you would expect, the Japanese invasion increased sales of BSAs, Triumphs and Harleys. But instead of reinvesting this income in improved productivity, the British companies only pushed existing equipment harder. Stockholders were happy, customers weren’t.

Despite ultimate failure, BSA leaves us with much to admire-a long history of motorcycles and the rich personalities associated with them. After the BSA exhibit opening, fellow CW editor Brian Catterson and I sat at lunch in a nearby restaurant with the four remaining riders from the 1954 Daytona sweep. The stories they told were as fresh as if practice were starting tomorrow morning at 8. Like racers of the current moment, these men are bright and charming, full of force and interest. Their wives are easily their equals in character and sparkle. Handsome women today, they were surely irresistible in the 1950s. These are not elderly retired folk who have pushed back from life’s table. They are laughing and talking, enjoying and living. Motorcycles are just one visible symptom of a strong life wish. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDer Meister Aller Klassen

September 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsAdventures In Fuel Mileage

September 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Combustion Compromise

September 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2004 -

Roundup

RoundupPower To the People!

September 2004 -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

September 2004