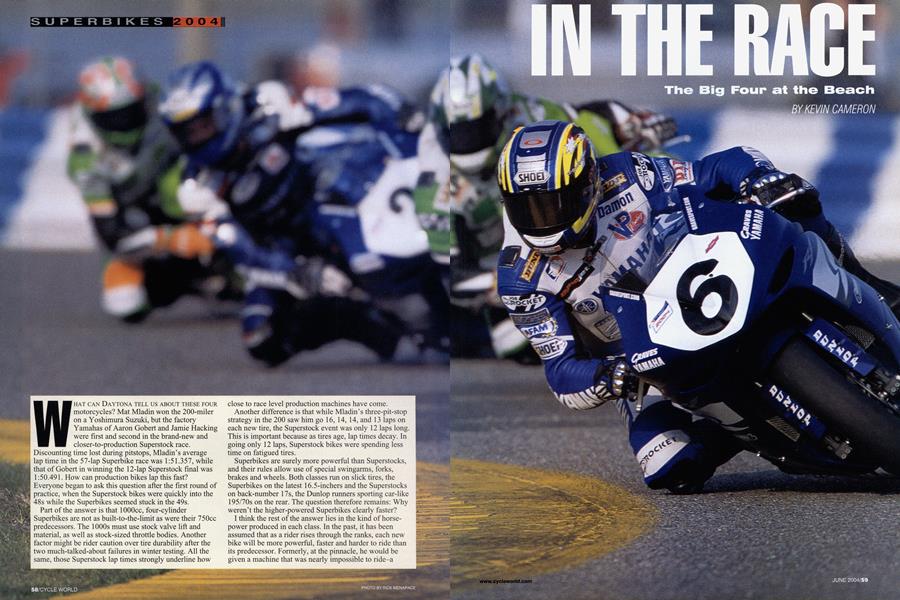

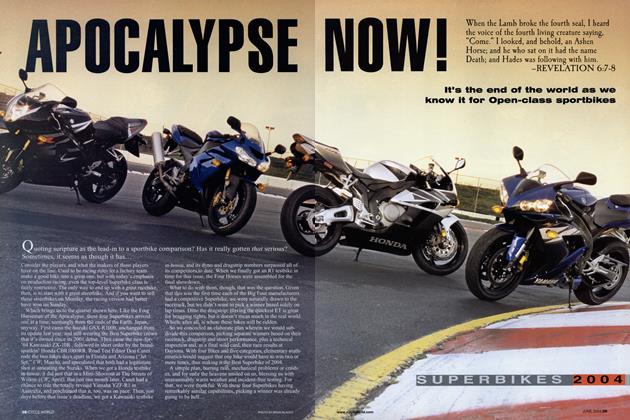

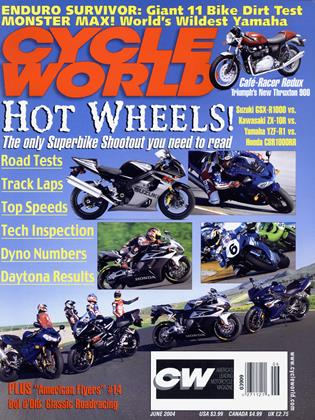

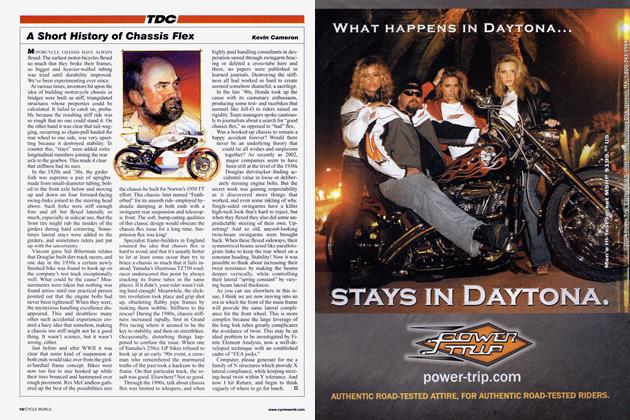

WHAT CAN DAYTONA TELL US ABOUT THESE FOUR motorcycles? Mat Mladin won the 200-miler on a Yoshimura Suzuki, but the factory Yamahas of Aaron Gobert and Jamie Hacking were first and second in the brand-new and closer-to-production Superstock race. Discounting time lost during pitstops, Mladin’s average lap time in the 57-lap Superbike race was 1:51.357, while that of Gobert in winning the 12-lap Superstock final was 1:50.491. How can production bikes lap this fast? Everyone began to ask this question after the first round of practice, when the Superstock bikes were quickly into the 48s while the Superbikes seemed stuck in the 49s.

Part of the answer is that lOOOcc, four-cylinder Superbikes are not as built-to-the-limit as were their 750cc predecessors. The 1000s must use stock valve lift and material, as well as stock-sized throttle bodies. Another factor might be rider caution over tire durability after the two much-talked-about failures in winter testing. All the same, those Superstock lap times strongly underline how close to race level production machines have come.

Another difference is that while Miadin's three-pit-stop strategy in the 200 saw him go 16, 14, 14, and 13 laps on each new tire, the Superstock event was only 12 laps long. This is important because as tires age, lap times decay. In going only 12 laps, Superstock bikes were spending less time on fatigued tires.

Superbikes are surely more powerthl than Superstocks, and their rules allow use of special swingarms, forks, brakes and wheels. Both classes run on slick tires, the Superbikes on the latest 16.5-inchers and the Superstocks on back-number 17s, the Dunlop runners sporting car-like 195/70s on the rear. The question therefore remains: Why weren't the higher-powered Superbikes clearly faster? I think the rest of the answer lies in the kind of horse power produced in each class. In the past, it has been assumed that as a rider rises through the ranks, each new bike will be more powerful, faster and harder to ride than its predecessor. Formerly, at the pinnacle, he would be given a machine that was nearly impossible to ride-a peaky, violent, 500cc twostroke Grand Prix bike. Under what I call The Old Paradigm, this progression was considered normal and proper.

IN THE RACE

The Big Four at the Beach

KEVIN CAMERON

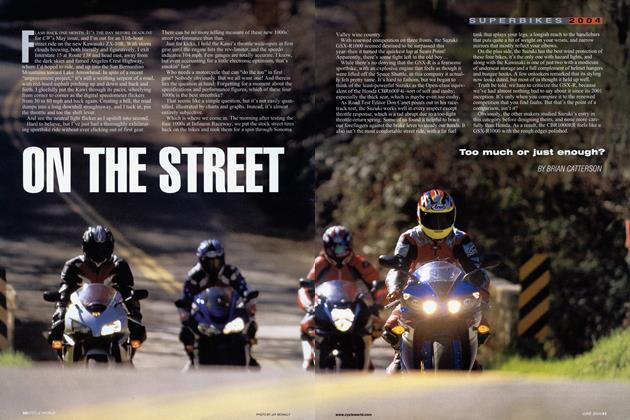

Today, most riders come up through 600cc production classes, where engine powerbands are amazingly wide and smooth. These riders therefore learn to use tire grip to the fullest because they can rely on the engine’s torque remaining smooth and nearly constant as they feed in throttle during comer exits. When such a rider is given a modified engine-with narrower power and a torque curve with peaks and dips in it-he has throttle modulation to think about as he exits each comer. This extra “processing load” naturally makes the rider’s mental “program” run a bit slower. But in the Superstock class, power curves are wide and smooth because these are streetbikes. This makes it easier to ride them closer to the limit than Superbikes.

Roger Lee Hayden, KawasakiZX-10R Superstock

flat Mladin, SuzukiGSX-R1000 Superbike

Ben Bostrom, HondaCBR1000RR Superbike

Add to this the recent remarkable growth in production engine power and you have the makings of what happened at Daytona-a production class running a faster race average than a modified class.

The New Paradigm is therefore that racebikes can be ridden faster when they are given production-bike power curves. I believe this is just what Honda has done in creating its RC211V MotoGP bike-a machine that has been proven easy for any good rider to ride fast.

The Honda team came to Daytona with considerable confidence it would win the 200. The new CBR1000RR was well engineered, very powerful and had posted an out-ofreach top speed of 193 mph. This expectation was to be disappointed, however, first by the speed of Eric Bostrom’s Austin Ducati 999, which set a new track record at a stunning 1:46.835—the first-ever 46 by a motorcycle. The next imponderable was the three-stop strategy adopted by Bostrom and Mladin. In the past, riders have stopped twice, changing tires as required and taking on fuel, going about 19 laps each stint. The change to three stops may initially have been driven by concern over tire reliability, but there proved to be more to it. When Mladin and his crew chief Peter Doyle looked at lap times through tire stints in previous Daytona 200s, they saw opportunity. At the beginning of the stint, the tire would permit 1:50s or even the odd 49. But as the stint ended, times decayed to 53s, 54s or worse. That suggested the question: How much time would be saved by chopping off the five slow last laps of three tire stints?

Enough to more than cover the 20 seconds an extra stop would add to the rider’s time? The rest is history: The strategy put Bostrom and his Ducati at the front early and, once the front-runners had spent themselves in various ways, put Mladin in command from lap 42 to the finish. All the power in the world is useless if it must be transmitted through a “tired tire.” You could see it on the track-as a rider’s tire aged, his bike would begin to visibly break away during the all-important drives off the chicane.

Had then-leading Bostrom’s chances not gone up in smoke from a split oil-cooler on lap 41, it would have been a close contest with Mladin to the very end. As it was,

Mladin’s three-stop strategy, combined with his proven GSX-R1000 and his strong riding, won the day. The object of racing is to win, and Mladin does that superbly. If fans want a folksy interview filled with comforting platitudes, they may have to look farther downfield.

What about Mladin’s partner in crime, his now-twoyear-old GSX-R1000? The Suzuki stands out with its oldstyle extruded frame side-beams, side-mounted muffler and one-ahead-of-the-other gearbox-shaft arrangement.

Are these serious disadvantages? Consider that the upper stages of countless satellite launchers are powered by the Pratt & Whitney RL-10 rocket motor-a design first drawn in the 1950s. Very often, proven performance is associated with a veteran design. Early Superbike leader Ben Bostrom was out of the race with “driveline difficulties” on his factory Honda, while eventual runner-up Jake Zemke said his Erion Racing Honda’s clutch made some disquieting noises at the start. No one can predict what Daytona will do to a new design.

On the other hand, new features seen on the three new models-for example, the stacked gearbox shafts and short engine length of the Yamaha and Honda-will surely be incorporated in the Suzuki at its next major revision. This is design convergence. New features interest us, but evidently they don’t determine the issue. Their value is demonstrably smaller than, say, the value of the threestop race strategy. What is important here is that all four of these machines are “in the zone.” Suzuki and Honda both led the 200, and Yamaha and Kawasaki were able to lead the Superstock event. Sprinkle the luck, tactics and riding a bit differently and the results could have been otherwise.

It must be remembered here that neither Kawasaki nor Yamaha is competing in Superbike this year; both are concentrating their resources in MotoGP. That makes Superstock the ideal means of showcasing their production machines. On the other hand, AMA rules require factory riders to pick only one class-Superbike or Superstock. Yamaha and Kawasaki deployed their top men in Superstock, where the highest-finishing Suzuki was that of polesitter Ben Spies in eighth. Canadian Jordan Szoke in 16th was the top-placed Honda.

You can be sure the tire companies were delighted when the Superstock event was shortened from 15 laps to 12.

Aaron Gobert, YamahaYZF-R1 Superstock

These bikes are 30 or more pounds heavier than Superbikes and go just as fast, so their tires were at greater risk. When Superbike was first added to AMA events in the 1970s, its races were short as well. As experience accumulated and reliability was enhanced by improved design, the races were made longer to the point that in 1985 Superbikes replaced Formula 1 machines in the 200.

Daytona picked two winners for us: Suzuki in Superbike (with the Hondas of rookie Zemke and veteran Miguel Duhamel 7-plus seconds behind), Yamaha in Superstock (in a tight draft of other Yamahas plus two Kawasakis). How can we choose between the two?

Winning Superbike seems like the greater achievement, but is it? To win in Superstock, a manufacturer must make all of the approved model’s production parts good enough for the job. To win in Superbike, a maker can enhance the basic engine and chassis with $30,000 forks and costly reengineering. The GSX-R1000 won partly because of basic design, partly by reason of race-only engineering and the usual unobtainium pieces.

Design and racing development (plus pit strategy) took the grueling 200-miler, but design largely unaided by special development took the much shorter Superstock event. This is clearly apples and oranges, but I’d give the Daytona nod to the YZF-R1.

ADVANTAGE: YAMAHA

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSecret Daytona

JUNE 2004 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsWhat To Do In Winter

JUNE 2004 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCA Short History of Chassis Flex

JUNE 2004 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

JUNE 2004 2004 -

Roundup

RoundupMonster Max!!!

JUNE 2004 2004 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupFormula Bmw: K-Bike Power For F-1 Hopefuls

JUNE 2004 2004 By Kim Wolfkill