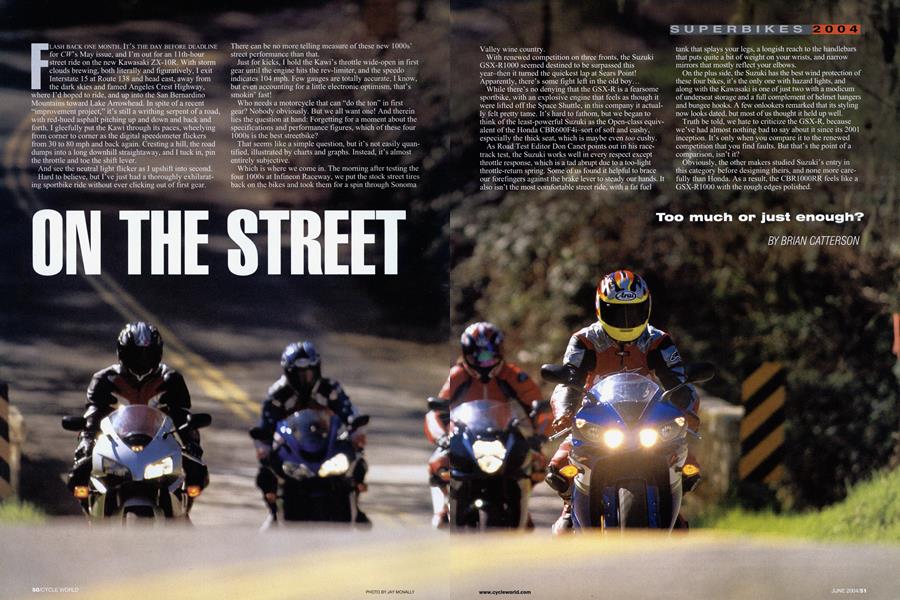

ON THE STREET

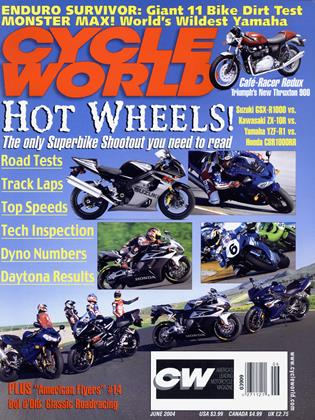

FLASH BACK ONE MONTH. IT’S THE DAY BEFORE DEADLINE for CW's May issue, and I’m out for an 1lth-hour street ride on the new Kawasaki ZX-10R. With storm clouds brewing, both literally and figuratively, I exit Interstate 15 at Route 138 and head east, away from the dark skies and famed Angeles Crest Highway, where I’d hoped to ride, and up into the San Bernardino Mountains toward Lake Arrowhead. In spite of a recent “improvement project,” it’s still a writhing serpent of a road, with red-hued asphalt pitching up and down and back and forth. I gleefully put the Kawi through its paces, wheelying from corner to corner as the digital speedometer flickers from 30 to 80 mph and back again. Cresting a hill, the road dumps into a long downhill straightaway, and I tuck in, pin the throttle and toe the shift lever.

And see the neutral light flicker as I upshift into second. Hard to believe, but I’ve just had a thoroughly exhilarating sportbike ride without ever clicking out of first gear.

There can be no more telling measure of these new 1000s’ street performance than that.

Just for kicks, I hold the Kawi’s throttle wide-open in first gear until the engine hits the rev-limiter, and the speedo indicates 104 mph. Few gauges are totally accurate. I know, but even accounting for a little electronic optimism, that’s smokin’ fast!

Who needs a motorcycle that can “do the ton” in first gear? Nobody obviously. But we all want one! And therein lies the question at hand: Forgetting for a moment about the specifications and performance figures, which of these four 1000s is the best streetbike?

That seems like a simple question, but it’s not easily quantified, illustrated by charts and graphs. Instead, it’s almost entirely subjective.

Which is where we come in. The morning after testing the four 1000s at Infineon Raceway, we put the stock street tires back on the bikes and took them for a spin through Sonoma Valley wine country. With renewed competition on three fronts, the Suzuki GSX-R1000 seemed destined to be surpassed this year-then it turned the quickest lap at Sears Point! Apparently, there’s some fight left in the old boy... While there’s no denying that the GSX-R is a fearsome sportbike, with an explosive engine that feels as though it were lifted off the Space Shuttle, in this company it actually felt pretty tame. It’s hard to fathom, but we began to think of the least-powerful Suzuki as the Open-class equivalent of the Honda CBR600F4i-sort of soft and cushy, especially the thick seat, which is maybe even too cushy. As Road Test Editor Don Canet points out in his racetrack test, the Suzuki works well in every respect except throttle response, which is a tad abrupt due to a too-light throttle-retum spring. Some of us found it helpful to brace our forefingers against the brake lever to steady our hands. It also isn’t the most comfortable street ride, with a fat fuel tank that splays your legs, a longish reach to the handlebars that puts quite a bit of weight on your wrists, and narrow mirrors that mostly reflect your elbows.

Too much or just enough?

BRIAN CATTERS0N

On. the plus side, the Suzuki has the best wind protection of these four bikes, it’s the only one with hazard lights, and along with the Kawasaki is one of just two with a modicum of underseat storage and a full complement of helmet hangers and bungee hooks. A few onlookers remarked that its styling now looks dated, but most of us thought it held up well.

Truth be told, we hate to criticize the GSX-R, because we’ve had almost nothing bad to say about it since its 2001 inception. It’s only when you compare it to the renewed competition that you find faults. But that’s the point of a comparison, isn’t it?

Obviously, the other makers studied Suzuki’s entry in this category before designing theirs, and none more carefully than Honda. As a result, the CBR1000RR feels like a GSX-R 1000 with the rough edges polished.

“The Honda’s refinement is unsurpassed, right down to its levers,” enthused Assistant Editor Mark Cemicky. “You just know it’s put together well.”

Like most Hondas, the RR is nicely styled, with a level of fit and finish not commonly found on production motorcycles. It has the best laid-out instrumentation of this group, the secondbest mirrors, and its clutch and brake levers are adjustable over five and six positions, respectively. Visually, the only pimple is the rear brake master cylinder, which is awkwardly located next to the right-side passenger peg hanger.

That refinement extends to the riding experience, as well. True to CBR900RR designer Tadao Baba’s “Bigger Circle” Theory, the RR is undoubtedly the best bike for the masses, with a level of user-friendliness the others simply can’t match. Its power curve defines the term “linear,” smooth and manageable down low and building gradually to its considerable peak, with precise throttle response and superb clutch and shift action. Stick it in a tall gear, abruptly open and close the throttle, and you may detect a bit of driveline snatch, but it’s not noticeable in normal use.

Wearing its standard-issue Bridgestone tires, the CBR is a sweet-handing machine, with neutral and relatively light steering that isn’t at all hindered by its trick electronic damper at street speeds-which, of course, is the point of the exercise. The ramp-style shock-spring preload adjuster is a step above the threaded collars on the Kawasaki and Suzuki, but fitting the special tool between the chain and swingarm is a bit of a chore.

Ergonomically, the RR is a mixed bag. The bar/seat/peg relationship is moderate, but the fuel-tank cover is on the wide side and the seat pad is thin and firm, though broad and flat. Other nits include a plastic fuel-tank cover that rules out magnetic tankbags, an underseat muffler that intrudes upon storage space and a complete lack of helmet hangers. Lastly, continuing a disturbing trend among Open-class Honda sportbikes, the RR got the worst fuel mileage of this lot, and thus has the least range. Add it all up, and the Honda just misses the mark.

As does the Yamaha, though for different reasons. The new, blue YZF-R1 is a great-looking bike, what with its cat’s-eyes headlights, underseat ray-gun muffler, black frame and racy-yet-tasty graphics. The blue dash lights are a thoughtful touch, too.

Helping the Yamaha’s cause on the street is its supple suspension, its hard-stopping-yet-manageable brakes and its natural riding position. Its fuel tank is nice and narrow, and the view over the low windscreen is unobstructed; it’s as though the bike disappears beneath you. While we’re looking forward, it’s interesting to note that the R1 has “radial”-style select and reset buttons for its dual tripmeters. As for looking backward, the wide mirrors offer the most unobstructed view of these four bikes. Its ramp-style shock-spring preload adjuster also makes suspension changes the easiest in this group.

Criticisms are few: The Y-shaped saddle is wide and supportive at the rear, but thin and narrow at the front where most riders will sit. The exhaust routing and underseat muffler bake your right instep and butt, particularly if you’re wearing jeans instead of leathers. The metal gas tank gives way to a plastic airbox cover at its forward edge, which makes using a magnetic tankbag sketchy. And the under-clutch actuating arm looks prone to damage in a tip-over, in spite of its small guard; surely a nylon frame slider jutting out from the swingarm pivot would offer additional assurance.

What hurts the Yamaha most as a streetbike, though, is its engine. It’s the smoothest of this lot, responsive and slickshifting, but its power delivery is atypical for a 1000. Openclassers are renowned for midrange lunge, but with its 10,000-rpm torque peak, the R1 feels like a 600 on steroids. Hold the throttle wide-open and you’ll find that the 13,000rpm R1 has the mother of all top-end rushes, but keep it below 7000 rpm and you could convince yourself that you were riding an R6.

Cemicky said it best: “You’ve got to rev the R1 like a blender on liquefy.”

Can’t say that about the Kawasaki. The big, blue Ninja has the mother of all midrange hits, accompanied by a telltale Kawasaki growl. It epitomizes everything we’ve come to expect from an Open-class sportbike engine, so forceful that you’d better be pointed in the right direction when you twist the throttle. You can pull out and pass a car on the Rl, no problem, but you can pull out and pass a dozen on the ZX-10R!

Like that other blue bike, the Kawi is great-looking, the best of the bunch in this author’s humble opinion. Ducati designer Pierre Terblanche once told me he appreciated Kawasaki’s styling because, like Ducati’s, their shapes were strong enough for solid colors-they don’t need graphics to save them.

Guest tester Ben Welch described the rakish Kawasaki best. “It looks like it’s doing a stoppie whenever the front wheel is on the ground,” he said.

The ZX-10R has a very sporty riding position, with a slim tank, cushy (but not too cushy) seat and purposeful (but not too purposeful) forward lean. It feels the most “stinkbug” of these four bikes at rest, but once you crack the throttle and the front end goes light, it feels much more natural. Which, considering how often the Kawi wheelies, is most of the time!

“I could probably get 20,000 miles out of the front tire,” joked Editorial Director Paul Dean.

ADVANTAGE: KAWASAKI

$10,999

Recent big-bore Kawasaki sportbikes have been hunkered-down on their suspensions, which enhances highspeed stability at the expense of harshness over smaller bumps. As delivered, our ZX-10 gave a hint of this behavior, but dialing out some compression damping gave it a permanent address in Cush City.

As for the transmission woes that plagued the Kawi on the racetrack, they never once manifested on the street-even after we’d had problems on the track-so we’d consider that a non-issue. The lack of a steering damper also didn’t bother us on public roads.

In the end, we could have made a strong case for picking any of these bikes as the winner, but chose the strongest of them all. In his own inimitable way, Cernicky summed it up best: “If there were four keys sitting on this table, I’d take the Kawasa-key.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSecret Daytona

JUNE 2004 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsWhat To Do In Winter

JUNE 2004 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCA Short History of Chassis Flex

JUNE 2004 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

JUNE 2004 2004 -

Roundup

RoundupMonster Max!!!

JUNE 2004 2004 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupFormula Bmw: K-Bike Power For F-1 Hopefuls

JUNE 2004 2004 By Kim Wolfkill