Bol d'Old

RACE WATCH

In vintage racing, three hours is a test of endurance

MARK GARDINER

THE FRENCH LOVE ENDURANCE RACING. WITNESS THE TOUR DE France or the Paris-Dakar Rally. It’s no surprise the 24-hour Bol d’Or roadrace, held every fall, remains the country’s highest-profile motorcycle event.

In order to recapture the glory of the race’s heyday in the 1970s, the Bol’s organizers created the Bol d’Or Classic. Since a full 24 hours would be too much to expect of motorcycles from that period (to say nothing of vintage riders), the format of the race is three one-hour sessions spread over 24 hours.

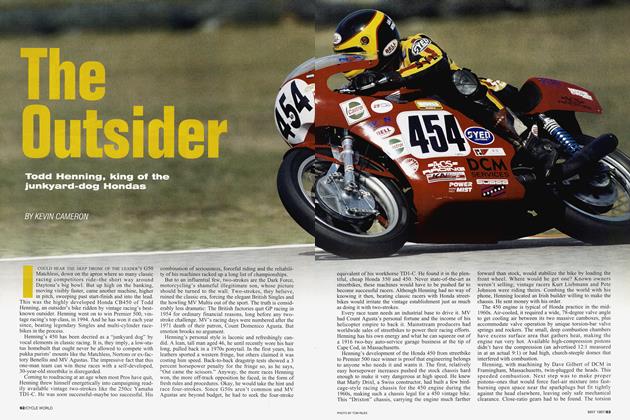

Vintage roadrace domo Patrick Bodden is the child of a French mother and an American G.I. He saw his first Bol ^Wásk in 1975 and was smitten. When he heard about the inaugural Bol d’Or Classic, he convinced Connecticut-based liflft Superbike collector Brian O’Shea to volunteer his exWËÉ works 1979 Honda RSI000, the machine that marked Honda’s return to roadracing and predecessor to Freddie Spencer’s Championship-winning Superbike. They entered the machine under Bodden’s “Heritage Racing” banner. Heritage Racing then recruited Reg Pridmore-best rememV bered as the first-ever AMA Superbike Champion in 1976-and Charlie Williams as co-riders. Williams is famous for his Isle of Man TT exploits, but he also rode Honda RCBs (the predecessor of O’Shea’s RS) for Honda in world championship endurance events.

The first practice sessions on Friday took place in blazing heat. Williams was first out for Heritage Racing, and brought the bike in noting that the brakes felt soft and the carburetion seemed rich. While Williams slumped in the cool of the garage, with a towel soaked in ice water around his neck, Pridmore took his turn in the leather sauna.

One garage over, a guy fettling a pair of Bimota HB-9s had stripped to his underwear. Not shorts, or a bathing suit, but actual Y-front briefs, on a body as pallid as a frog’s belly, except where it had already been sunburned (he’d been outside in the line to register for the event, in the same utterly unselfconscious state, at high noon). His team, on the entry list as Forza Bimota, seemed to be sponsored by a gentleman’s club that had sent along a few girls, dressed for their part in Bimota T-shirts the size of Barbie clothes.

“Why don’t we have any hookers?!” O’Shea asked, in a tone suggesting that by comparison, Bodden had already failed as a team manager.

Despite their storied careers, Pridmore and Williams never had much luck at the Bol. Pridmore rode an R100 for the French BMW importer in 1975. “They were putting oil in each time we stopped to refuel, but not as much as it was burning,” he said, recalling the inevitable conclusion. “It stopped once and for all somewhere around the sixth hour.” Williams rode in world championship endurance events from 1973 to ’78, scoring only one finish in five Bol starts.

On Saturday after timed qualifying, it seemed that run of luck had changed. Williams’ fastest lap-a 2:06-flat-was good enough for fourth spot on the grid. In front of their RS was a legendary Godier-Genoud Kawasaki, piloted by endurance ace Alain Genoud himself and Gilles Hampe (one of France’s most charming and fastest motorcycle cops.) There was also a brutal-but-effective Yamaha TZ750 and a deceptively quick Moto Guzzi Le Mans.

On Sunday afternoon, Williams lined up on the far side of the track with 40some other riders. The flag dropped, and there was an eerie moment of silence, but for the patter of feet in racing boots, as the riders ran across to their machines.

Bike owner O’Shea watched the first few laps from Turn 1, returning a little shocked after seeing Williams riding his irreplaceable motorcycle in very hot pursuit of ex-world champ Jean-Claude Chimaron. “Man,” he said, “those guys are having a duel!”

The rules called for a rider change between the 20and 40-minute marks of each session. Pridmore brought the first hour to an uneventful close with Heritage Racing listed in sixth place.

The Sunday-night session saw Williams get off to another good start, but after a few laps the announcer mentioned that he was off the track at the “180,” a hairpin turn about as far from the pits as could be. With no additional information from the loudspeakers, Heritage Racing didn’t know if Williams had crashed or broken down. Bodden trotted off to race control, where the entire track (built to Formula One car specs) was covered by a closed-circuit television system. In the cool, dark control booth, facing a bank of video monitors, he watched Williams push the big Honda up a long hill. O’Shea, meanwhile had taken off at a run, back along the track’s service road, hoping to find him.

“Here he comes!” someone yelled. Williams-soaked in sweat but now back on the machine-was pushed the length of the pit lane by Bodden and O’Shea. Hope springs eternal in endurance racing. Could it just be fuel starvation? The fuel tank vent hose seemed kinked. O’Shea ripped it off, and punched the starter. It started all right-started making loud metal-on-metal banging noises from the top-end! Pridmore pulled off his leathers.

Bodden and O’Shea mulled over an apparently hopeless situation. The team had brought virtually no spare parts, as most were simply unavailable. “As much as this looks like a streetbike motor,” bemoaned O’Shea, “inside it’s so different.” One by one, the garages fell silent. The third and final session would be flagged off Sunday at 3 p.m. Bodden and O’Shea took turns: One would find the situation impossible, while the other proposed some solution that was merely improbable. “Has anyone walked through the swapmeet? Maybe there’s a CB1100F valve set down there,” Bodden wondered out loud. “If the valves were the right size, the head might work converted to shimover-bucket...” His voice-and optimism-waned in mid-sentence. From the infield, behind the darkened and empty grandstand, came the sounds of a band covering old American rhythm-andblues songs. At midnight, Bastille Day fireworks went off.

If the two of them had ever given up hope at the same moment, the story would have ended right there. But a sentence stood out at the top of the old Honda parts list: “The motor is based on the CB750/CB900F series.”

O’Shea mused, “What if we could just take the head off a 900 and drop it straight on?” Next door, the strange guy in his skivvies was still puttering around. Their team’s spare Bimota had just such a motor. Out of options, Bodden went over to ask if they could borrow it. Without a second thought, the Frenchman wheeled the Bimota into Heritage Racing’s garage and began prepping the machine as a donor.

At 2:54 a.m., the first wrench was thrown. The camchain slipped down just far enough for a few links to kink and jam under the lower sprocket. Bodden and O’Shea jerked and cursed like Tourette’s patients for five minutes before it came free.

Underwear Man was in the background, not wanting to get in the way, but ready to help if he could. Smiling to himself in a way that conveyed there was nowhere else in the world that he’d rather be, he said (I’m translating here, because he spoke no English at all), “No matter what happens, this is already enough to make a beautiful memory.”

Maybe, but the RS’s cylinder head was ugly. One of the original Ti exhaust valves had snapped and slammed into the roof of the combustion chamber. Luckily, it sliced into the aluminum head and stuck there. While the piston crown was scarred, it did look remotely serviceable.

At 3:33 a.m., Bodden, who speaks fluent French, turned to Monsieur Skivvies (whose name we’d learned was Denis Malterre) and asked, “So, where are you from?”

He was from Ault, a little town near Dieppe. He was a cantonnier. We didn’t recognize the word, but he mimed his job, sweeping local streets with a broom.

Malterre attended every Bol d’Or from 1970 to 1986. “All my life,” he told us, “I dreamed of being on this side of the straightaway.” But in 1986 he was injured in a terrible accident that killed his wife. Then he knew: His dream was not going to come true. So, the street sweeper put thoughts of the Bol aside and raised his son alone. The kid-here this weekend racing his dad’s bike in his first race ever-had become a biology professor in Switzerland.

The pair of Bimotas were both bought as junkyard wrecks for less than a thousand francs (about $150). It took 15 years of broom-pushing to save enough money to restore and race-prep them. This event (for which a full race license was not required) was the little family’s once-in-a-lifetime shot. “For me,” Malterre said, “racing is impossible. But now I hand the baton to my son.”

On Monday morning, the trickle of curious bikers from the previous night picked up at Garage 39. They whispered and pointed into an oily cardboard box shoved out of the way in a corner. The factory cylinder head had been ported by the legendary Jerry Branch, who had once fettled Kenny Roberts’ Yamaha flat-trackers. Now, it looked as forlorn as a dead deer dangling off the tailgate of some cowboy’s pickup truck with its tongue lolling.

Bodden and O’Shea wrestled the motor-now sporting Forza Bimota’s CB900F head-back into the frame. The big Honda roared back to life, sounding as though nothing had ever been wrong. But after losing virtually all of the second session to their broken valve, Pridmore and Williams were listed in 31st place, 25 laps behind the leading Guzzi. Bodden ordered the riders to baby the motor and circulate. Just getting to the checkered flag would constitute a victory under the circumstances.

That was the plan. But on the third and final drop of the green flag, Williams stalled the bike. Somehow, it had been gridded in second gear. The entire field streamed past him and the plan exploded in a red mist. Williams passed 12 riders on the opening lap, eight more in the next four corners. The track announcer went hyperbolic. Then we heard a fateful, “Williams has pulled off!” The motor had tightened up. Pridmore wriggled out of his leathers without turning a wheel. Again.

Heritage Racing pretty much shut down the beer concession before even starting to pack. “Next year, I’m coming back with a cheater motor from Hell,” O’Shea vowed. Williams headed back to his home in Cheshire, England. Pridmore and his girlfriend went off to do a little sightseeing. Bodden and O’Shea drove to the freight terminal at Charles de Gaulle.

In a final Freudian slip, they forgot their little “participants” trophy on the rental van’s dashboard. After having traveled the longest distance and fielded the rarest of machines; after having their hopes raised and dashed, raised and dashed; after working through the night; after all that, no one deserved to see the checkered flag more.

Except for Denis Malterre and his Forza Bimota squad. “This has been the weekend of my life,” Malterre’s son David told me. They took the checkers in eighth place, never mind that every team ahead of them had a real racing pedigree, as did most of the 30-plus teams that finished behind them. If you’re only ever going to do one race, that’s a helluva good way to do it.

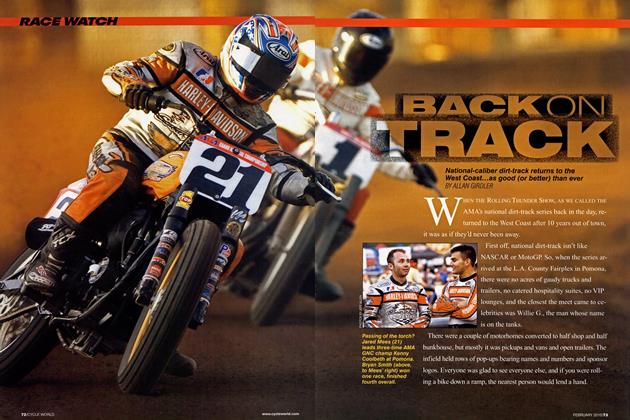

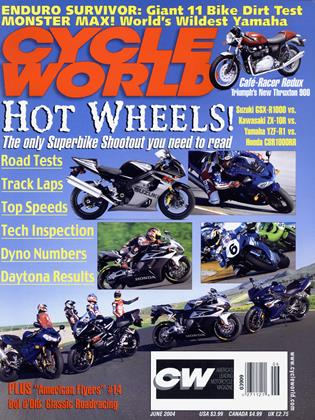

Daytona Middleweight Mixup: 600cc x 2

Oh, the tangled web we weave. AMA rules changes leave the highly competitive 600cc Supersport class as-is, catering to stock bikes with limited tuning and suspension changes. Replacing the former lOOOcc Formula Xtreme is a 600cc version-best described as 600 Superbike, for that is what it will surely become if the present Superbike formula devolves into a tire-nursing class.

Now for the stunner: At the season opener in Daytona, Supersport 600 was faster than Formula Xtreme 600. I love this kind of upset. It forces us all to rethink our most cherished assumptions, such as modifying bikes makes them faster.

Jason DiSalvo was top Supersport qualifier on a factory Yamaha YZF-R6 at a 1:50.998-a time that would have placed him eighth on the Superbike grid. Top man in Formula Xtreme was Ben Bostrom on a Honda at 1:52.800. How’s that for backward? Average times of the top 10 qualifiers were 1:52.445 for Supersport and 1:55.227 for Formula Xtreme. How can production bikes be faster than fully modified racebikes?

Those who should know said that the slicks on the Formula Xtreme bikes were really too big for them, while the Supersport machines thrived on stock rims with DOT rubber, but street tires are illegal in Formula Xtreme.

Another factor: New rules require factory riders to pick one class from each pair: Supersport vs. Formula Xtreme, and Superbike vs. Superstock. As a result, Honda’s Miguel Duhamel and Bostrom were absent from Supersport, assigned to the class they could win-Formula Xtreme.

In the FX final, Duhamel and Bostrom had the front to themselves with Erion Honda’s Jake Zemke working to overcome Yamaha-mounted Pascal Picotte to claim the final podium position. Zemke’s teammate, Alex Gobert, also got past Picotte, bumping the Canadian to fifth. On the last lap, Bostrom held the desired slingshot, running in second position off the chicane, but a steep dive down the east banking by Duhamel broke the draft and secured the win. Formula Xtreme attracted only 16 starters-and criticism that the elimination of 750 Supersport did away with the last class in which privateers had a shot at making an impression.

The AMA has always been internally divided between the need to “streamline for TV” and the American populist ideal that everyone deserves a place on the starting grid. Unfortunately, it has become difficult to safely combine professionals racing at 10/ioths, with recreational racers. The faster rider has almost no tire grip left in reserve with which to maneuver, while the slower ones have enough to make sudden course changes that a faster rider cannot follow. The necessary result has been the 112 percent rule, limiting starters to a lap time no slower than 112 percent of the pole time. At Daytona, this meant the race leaders would begin lapping tail-enders in about eight laps.

Formula Xtreme is new-entries will increase over time. In 1982, when the AMA reduced Superbikes from 1025 to 750cc, American Honda’s then-tech chief Udo Gietl remarked that Superbike might one day have to be further reduced to 600cc. Time will tell.

Supersport ran before the 200, both taking place on Saturday instead of the traditional Sunday. This change was made in hope that more spectators would attend if Sunday were available for their journey home. It seems to have worked-the infield was packed and respectable numbers dotted the vast grandstands. Hayden brothers Tommy and Roger Lee were away first on their Kawasakis, but as always, the pack’s draft made it impossible for any rider to pull clear. As Kurtis Roberts said a year or two ago, “There’s not a lot of racing going on until the last three laps.” Then came two red flags-the first for a crash and another caused by an oil spill-cutting the race’s average speed to a dismal 42 mph.

I wish some bored CFD expert would model airflow around a drafting pack of bikes-there would be some surprises. In the real world, riders can slingshot from sixth or eighth into the lead, while others lose an equal number of positions. Very few are masters of this situation and Duhamel is “da man” when it comes to working the slipstream. He drops mysterious hints like, “I couldn’t feel anyone behind me.” I suspect that when a rider is running alone, flow separates from his back, causing his leathers to lift. When someone is close behind, the flow separation is postponed, allowing the leader to feel the difference. Fascinating things to be learned!

In the last-lap drafting war, Tommy Hayden tried to drive through under DiSalvo as both closed, low down, on the finish. DiSalvo firmly shut him off, while Roger Lee “found air,” tugging him into second place at the stripe. The final order was DiSalvo, then the Haydens, with Yamaha’s Aaron Gobert and Jamie Hacking rounding out the first five. The top 10 included five Yamahas, two Kawasakis and three Suzukis.

Why is 600cc Supersport currently faster than Formula Xtreme? First, it has now become very difficult to improve on stock. And second, I think the wide, smooth power of a stock engine more than makes up for the possibly greater but certainly harder-to-use power of a modified engine. Surely, more sophisticated Formula Xtreme engines are in the works. -Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

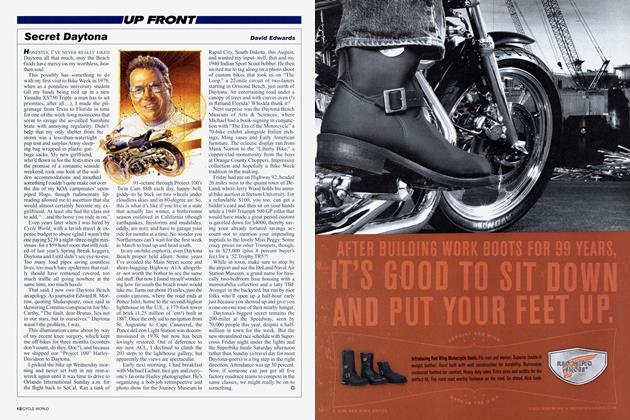

Up FrontSecret Daytona

JUNE 2004 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsWhat To Do In Winter

JUNE 2004 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCA Short History of Chassis Flex

JUNE 2004 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

JUNE 2004 2004 -

Roundup

RoundupMonster Max!!!

JUNE 2004 2004 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupFormula Bmw: K-Bike Power For F-1 Hopefuls

JUNE 2004 2004 By Kim Wolfkill