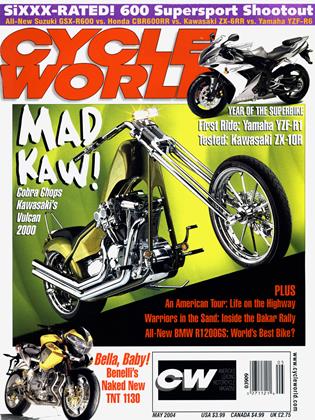

YAMAHA M1

Riding a MotoGP weapon—think of it as YZF-R12

NICK IENATSCH

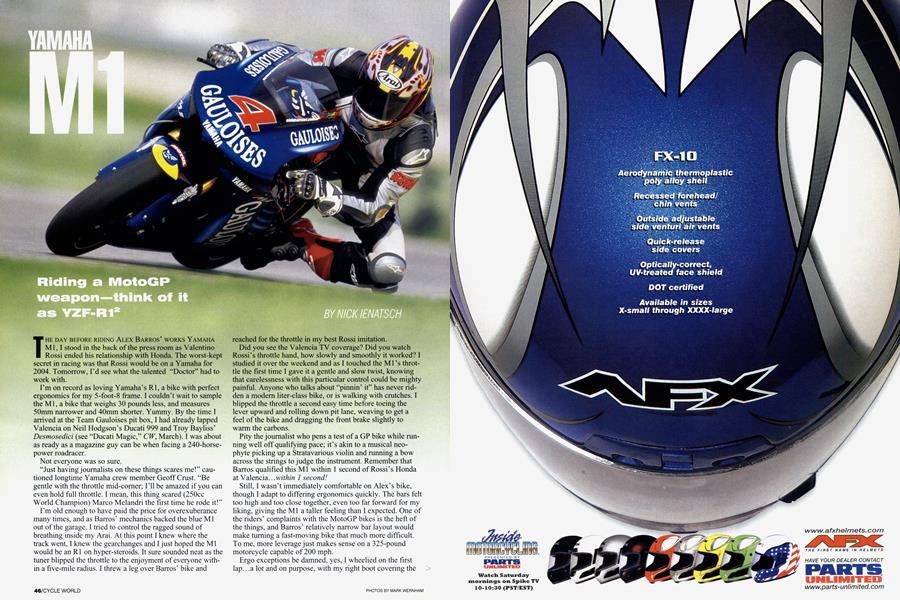

THE DAY BEFORE RIDING ALEX BARROS’ WORKS YAMAHA M1, I stood in the back of the press room as Valentino Rossi ended his relationship with Honda. The worst-kept secret in racing was that Rossi would be on a Yamaha for 2004. Tomorrow, I’d see what the talented “Doctor” had to work with.

I’m on record as loving Yamaha’s Rl, a bike with perfect ergonomics for my 5-foot-8 frame. I couldn’t wait to sample the Ml, a bike that weighs 30 pounds less, and measures 50mm narrower and 40mm shorter. Yummy. By the time I arrived at the Team Gauloises pit box, I had already lapped Valencia on Neil Hodgson’s Ducati 999 and Troy Bayliss’ Desmosedici (see “Ducati Magic,” CW, March). I was about as ready as a magazine guy can be when facing a 240-horsepower roadracer. Not everyone was so sure.

“Just having journalists on these things scares me!” cautioned longtime Yamaha crew member Geoff Crust. “Be gentle with the throttle mid-comer; I’ll be amazed if you can even hold full throttle. I mean, this thing scared (250cc World Champion) Marco Melandri the first time he rode it!” I’m old enough to have paid the price for overexuberance many times, and as Barros’ mechanics backed the blue Ml out of the garage, I tried to control the ragged sound of breathing inside my Arai. At this point I knew where the track went, I knew the gearchanges and I just hoped the Ml would be an Rl on hyper-steroids. It sure sounded neat as the tuner blipped the throttle to the enjoyment of everyone within a five-mile radius. I threw a leg over Barros’ bike and reached for the throttle in my best Rossi imitation.

Did you see the Valencia TV coverage? Did you watch Rossi’s throttle hand, how slowly and smoothly it worked? studied it over the weekend and as I touched the M1 ’s throttle the first time I gave it a gentle and slow twist, knowing that carelessness with this particular control could be mighty painful. Anyone who talks about “pinnin’ it” has never ridden a modem liter-class bike, or is walking with crutches. I blipped the throttle a second easy time before toeing the lever upward and rolling down pit lane, weaving to get a feel of the bike and dragging the front brake slightly to warm the carbons.

Pity the journalist who pens a test of a GP bike while running well off qualifying pace; it’s akin to a musical neophyte picking up a Stratavarious violin and running a bow across the strings to judge the instrument. Remember that Barros qualified this Ml within 1 second of Rossi’s Honda at Valencia...within 1 second!

Still, I wasn’t immediately comfortable on Alex’s bike, though I adapt to differing ergonomics quickly. The bars felt too high and too close together, even too far forward for my liking, giving the Ml a taller feeling than I expected. One of the riders’ complaints with the MotoGP bikes is the heft of the things, and Barros’ relatively narrow bar layout would make turning a fast-moving bike that much more difficult. To me, more leverage just makes sense on a 325-pound motorcycle capable of 200 mph.

Ergo exceptions be damned, yes, I wheelied on the first lap...a lot and on purpose, with my right boot covering the rear brake just in case. I needed to get a feel for the bike’s power right away, while straight up and down. These were gradual, smooth power-wheelies in second and third gear, accomplished simply by rolling on more and more throttle. Acceleration seems limitless on these bikes, especially on the short, tight, technical Valencia circuit. You want more acceleration, a higher wheelie? Twist it a little more. I did and it felt so right...and so fun!

“These things have useable power, they’re not just trying to kill you all the time. They pull for days and you’ll love riding it,”

Team Repsol stud Nicky Hayden clued me in before my Ml stint. “Hey, I’m just killing time until 1 get to ride mine again.”

Still, I never got comfy with Barros’ bar layout, and the best way I can describe it is to have you try some pushups: first with your hands 12 inches apart on either side of your head; then with your hands placed just outside your shoulders. The wider stance is more stable and Barros’ cramped bar position made the bike feel less stable. I never felt in touch with the rear tire’s contact patch in the same way I did on Bayliss’ Ducati-and I got twice as many laps on the Yamaha. Seems I’m not alone on this.

“We can do many good things with fork and shock adjustments,” said Fiorenzo Finali, Fortuna Yamaha crew chief, “but improving the chassis is (a job) for Yamaha.”

So far in pre-season testing, with at least one chassis change and two engine tweaks, Rossi and the new M1 have been impressive, running with the Hondas and Ducatis in both Malaysia and Australia.

By comparison, the Ducati transferred weight backward under acceleration well enough for me to play with rear grip. I didn’t feel as free on the Yamaha. Valencia has an uphill sweeping left-hander that is perfect for finding the edge of traction at the rear, but as I experimented with the Ml’s scalpel-sharp line, 1 felt myself on the verge of being sliced badly. Rather than load the tire and then let it break away with just a touch more throttle, the Yamaha stuck tenaciously, but offered little information on when the rubber would begin to slide.

Ah, but the front end with its Ohlins fork and Brembo radial brakes! The data acquisition from my best lap showed my exit speeds were relatively close to Alex’s best lap, while my entrance speeds were significantly slower. Alex later confirmed that he, too, was less than enthusiastic about rear traction feedback, but his entrance speeds were what kept him close to the Hondas. Most riding mistakes begin with a rushed entrance, especially while learning a track, and I was determined not to make a silly mistake at the entrance. But as the laps wound down, I was letting the Yamaha carry more and more speed into the comers. It never let me down, never missed an apex.

On my last green-flag lap, I had an epiphany in Valencia’s Turn 1 that I hope I can adequately describe. All weekend I had watched my heroes drive to the end of pit wall before squeezing on the brakes in sixth gear and downshifting to second for the corner. Not wanting to be an idiot, I had been rolling off and braking early, but the M1 radiated confidence and on that last lap I went all the way to the end of pit wall, just like the big boys. I was committed-pavement, curbs, grass and gravel streaming at me like a DVD on X-50. This sounds silly, but the Ml felt so awesome that I had the impression that its entrance speed was unlimited...like I could run full throttle into every comer and just rail through. The better you ride, the more you realize this impression is physically impossible, but it’s the feeling I had on that last lap-whatever entrance-speed bravado I could muster, the Ml could handle. I’ve never had that feeling before, even after 10 years of racing a TZ250.

My time on Barros’ Yamaha and Bayliss’ Ducati convinced me that four-stroke GP racing will fuel every enthusiast’s passion for years to come. MotoGP bikes will be available as streetbikes very soon because they offer everything you and I want in a sportbike: tractability, adjustability and thrillability. All that, and the government’s clean-emissions stamp of approval. Despite the six two-stroke racebikes in my garage, this Valencia experience forces me to admit that four-stroke MotoGP bikes rule.

Oh, and good luck, Valentino.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMending History

May 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Forgotten Passenger

May 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCInvisible Seal

May 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

May 2004 -

Roundup

RoundupDy-No-Mite! Benelli Unveils Tnt Naked Bike

May 2004 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupVtx Show-Shocker

May 2004 By Mark Hoyer