SPEED JUNKIES HALL OF FAME

SPEED IS ITS OWN REWARD, AND THESE 10 ADDICTS-LED BY DON VESCO, THE FASTEST, AND ELMER TRETT, THE QUICKEST-BELIEVE YOU CAN NEVER GET ENOUGH OF IT

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

Don Vesco

A GRAY-HAIRED DON VESCO SETTLES INTO A worn, vinyl rocker and spins around reluctantly to answer the phone at his race shop in Temecula, California. Cosworth Indy-car engines surround him; there’s a retired Offenhauser sitting in the middle of the room and several motorcycle and boat engines consume any remaining bench space. The shop is far from well-organized, but if you’re addicted to speed like Vesco is, you find what you need.

Vesco set the motorcycle land-speed record at 318.598 miles per hour in 1978 with a streamliner powered by twin Kawasaki KZ1000 turbocharged engines. But with the improved technology of today, he thinks that record can be broken easily. And he would like to do it. “I think a motorcycle can go over 400 miles per hour,” says the 50-year-old Vesco. “It’s a long way from 318, but it can be done.”

Certainly, Vesco’s record will one day be broken; in fact, there are rumors of upcoming attempts by at least two Harley teams. But that the record he set has remained untouched for 10 years attests to just how difficult the task really is.

Yet, to hear Vesco talk, getting up to 318 miles an hour was not that difficult.“I had been having problems and was running way under 300 all week. Then on Friday, things came says matter-of-factly. “Then a TV crew showed up and asked if I could do it again. So I did and went 318, no problem. I guess on the dragstrip, every tenth-of-asecond quicker is a big step up, but at Bonneville, it’s more difficult to tell how fast you are going.” One reason is that even though there’s a lot of noise in a streamliner, the wind roar is not as loud as you would expect from a 318-mph projectile. “You can hear the engines screaming at 11,000 rpm, but no exhaust and little wind,” Vesco says.

About the only way to get a sense of speed at Bonneville is from the black stripe that runs down the center of the course. “Whoever put that stripe there must have had one too many beers, because it’s not straight,” Vesco says. “So when you get up to serious speeds, that thing starts to snake and wiggle at you.”

Today, Vesco returns to Bonneville every chance he gets, running everything from 425-mph cars to built-up motorcycles. “I’d go every day if I could,” he says. “There is no other place where you can go that fast.” And if the rumors of an attempt at his record turn out to be true, Vesco just may be back on the salt going for 400 on two wheels. As he says, “I don’t want to go out and bump the record just a little, I want to set it where it’s a challenge to go for it.”

Joe Petrali

MANY PEOPLE BELIEVE THAT JOE Petrali was the greatest America^, racer of all time. He won more national races than anyone, by some accounts more than 50, and was the national hillclimb champion eight times. In 1937, he rode a 1 OOOcc Harley-Davidson right into the record books with a 136.183-mph pass at á|aytona Beach, then the location of choice for top-speed events. The bike was designed to be partially streamlined, but for the record run the bodywork was removed due to instability problems.

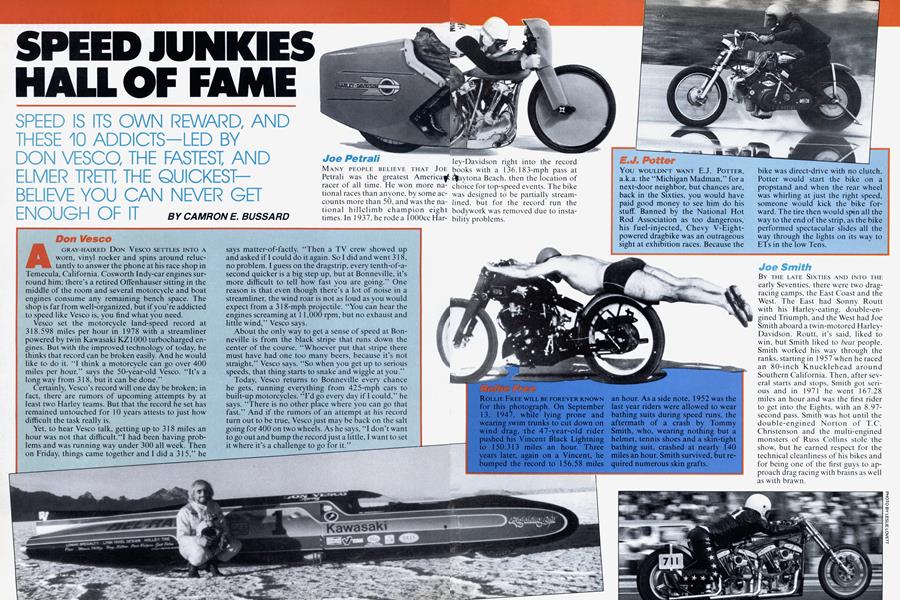

Rollie Free

ROLLIE FREE WILL BE FOREVER KNOWN for this photograph. On September 13, 1947, while lying prone and wearing swim trunks to cut down on wind drag, the 47-year-old rider pushed his Vincent Black Lightning to 150.313 miles an hour. Three years later, again on a Vincent, he bumped the record to 156.58 miles an hour. As a side note, 1952 was the last year riders were allowed to wear bathing suits during speed runs, the aftermath of a crash by Tommy Smith, who, wearing nothing but a helmet, tennis shoes and a skin-tight bathing suit, crashed at nearly 140 miles an hour. Smith survived, but required numerous skin grafts.

E.J Potter

YOU WOULDN’T WANT E.J. POTTER, a.k.a. the “Michigan Madman,” for a next-door neighbor, but chances are, back in the Sixties, you would have paid good money to see him do his stuff. Banned by the National Hot Rod Association as too dangerous, his fuel-injected, Chevy V-Eightpowered dragbike was an outrageous sight at exhibition races. Because the bike was direct-drive with no clutch, Potter would start the bike on a propstand and when the rear wheel was whirling at just the right speed, someone would kick the bike forward. The tire then would spin all the way to the end of the strip, as the bike performed spectacular slides all the way through the lights on its way to ETs in the low Tens.

Joe Smith

BY THE LATE SIXTIES AND INTO THE early Seventies, there were two dragracing camps, the East Coast and the West. The East had Sonny Routt with his Harley-eating, double-engined Triumph, and the West had Joe Smith aboard a twin-motored HarleyDavidson. Routt, it’s said, liked to win, but Smith liked to beat people. Smith worked his way through the ranks, starting in 1957 when he raced an 80-inch Knucklehead around Southern California. Then, after several starts and stops, Smith got serious and in 1971 he went 167.28 miles an hour and was the first rider to get into the Eights, with an 8.97second pass. Smith was hot until the double-engined Norton of T.C. Christenson and the multi-engined monsters of Russ Collins stole the show, but he earned respect for the technical cleanliness of his bikes and for being one of the first guys to approach drag racing with brains as well as with brawn.

Bill Johnson

BILL JOHNSON’S I 962 RECORD OF 230.269 miles an hour was important for more than just the speed he achieved. His 17-foot-long streamliner, powered by an alcohol-burning, 650cc Twin fitted with off-the-shelf racing parts, was the first Triumph to hold an absolute speed record recognized by both the AMA and Europe’s FIM, ending a six-year controversy over who really held the record. That controversy revolved around Texan Johnny Allen’s 1955 192-mph speed at Bonneville that was timed by Americans but not recognized by the FIM. By 1966, when Bob Leppan’s Gyronaut X-1, a twin-engined, 650cc Triumph streamliner, raised the record to 245, American speed addicts had simply bypassed FIM sanctioning, considering Bonneville clockings the only validation needed for the world's fastest motorcycles.

Russ Collins

ONE OF THE MOST-INNOVATIVE OF drag racers, Russ Colllins was the first to capitalize on the potential of the Honda 750 inline-Four. In the early Seventies, he put three Honda 750 engines in one chassis. Collins, known as “The Assassin” in tribute to all the records he had previously done away with, and his gifted engine builder, Byron Hines, soon had the Honda Triple cranking. The bike, known as “Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe,” logged an 8.55-second pass at 166 miles per hour its first time out, eventually recording a 7.86 at 179 miles an hour. But a crash in 1976 ruined the bike and nearly killed Collins. Undaunted, Collins built the “Sorcerer,” a 2000cc, VEight Honda and did a 7.5 quartermile at 199 miles an hour in 1978. He then retired the bike, and turned the racing chores over to one of his employees, a young Terry Vance.

Jon McKibben

THE SAGA OF THE 1972 HONDA HAWK effort shows just how potentially dangerous speed-record attempts can be. The Hawk streamliner held two Honda turbo 750s, making nearly 300 horsepower. Ridden by Jon McKibben, the bike indicated it was fully capable of taking the record265 miles per hour—away from Harley-Davidson when it hit 285 during preliminary runs. Unfortunately the bike also crashed, forcing the team to work overtime to get the bike ready for another crack at the record. During the next attempt, as the bike swept to 267 miles an hour, disaster struck. The Hawk began to swerve, and, as McKibben fought desperately for control, it lurched off the course. McKibben pulled the highspeed parachute, but the bike still was launched 20 to 30 feet into the air when it hit rough terrain. When the Hawk tumbled back to the salt flats, it disintegrated, ending Honda’s hopes of taking the record away from Harley. Amazingly, McKibben walked away from the crash.

Terry Vance

TERRY VANCE GOT HIS UNDERGRADUate degree in speed under the guidance of Russ Collins, but his graduate work was a tag-team effort with tuner Byron Hines. The pair eventually locked up 13 national championships, devastating the competition in every class they entered. When everyone else raced Harleys, they chose Hondas or Suzukis. When other guys were tapping on the door of 200 miles an hour, Vance kicked it down with a 203 at a Wednesday-night grudge match. Vance went on to becomethe most-successful motorcycle drag racer in history before retiring at the end of the 1988 season to concentrate on his aftermarket business.

Elmer Trett

OU’VE GOT TO WONDER WHAT’S WRONG WITH

this guy. He’s almost old enough for a pension, and should be spending Saturdays mowing the grass, Sundays watching the grandchildren. But not Elmer Trett. This graying 47year-old spends his weekends pulling the trigger on a 750-horsepower, 1325cc, supercharged Kawasaki.

Trett has spent so many weekends inhaling the aroma of burning rubber and nitromethane, he can’t remember when he wasn’t racing. “I think,” he says, “I have always done it.” But in the last several years, Trett has been at the forefront of the sport. He was one of the first riders to do 200 miles an hour in the quarter-mile, and now leads the way with an unsanctioned run that hit 213 with an ET of 6.60 seconds.

That run is simply amazing, and hard to describe. “The bike lifted its head hard and quick, and almost pulled out from under me,” Trett says. “It was an unbelievable run. When I stopped at the end, I knew it was faster than I had ever gone in my life. I looked down and the brakes were smoking and the discs were glowing red hot. It definitely got my attention.”

To go that fast, Trett has spent the last five years fiddling on his handbuilt Kawasaki. It says “Kawasaki” on the engine, but there aren’t too many original factory pieces left. He has built a custom bottom end and forged a one-piece, six-main-bearing crankshaft. “I fit the parts and make most of them,” he says.

Now that he has gone 213, Trett would like to see 218, but believes that setting goals can be a detriment to competition. “The race for 200 was a big thing, but it got in the way of racing,” he explains. “We were all pushing for it, but I finally decided to concentrate on winning races rather than going for the number. The next thing you know, I was the first to hit 200 in a sanctioned meet.”

For now, there is no end in sight for Trett. “I love the sport. I said three years ago that I would quit the next year, and now I would like three more. To me, going quick and fast is an attitude, and right now I’m greedy.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

October 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1989 -

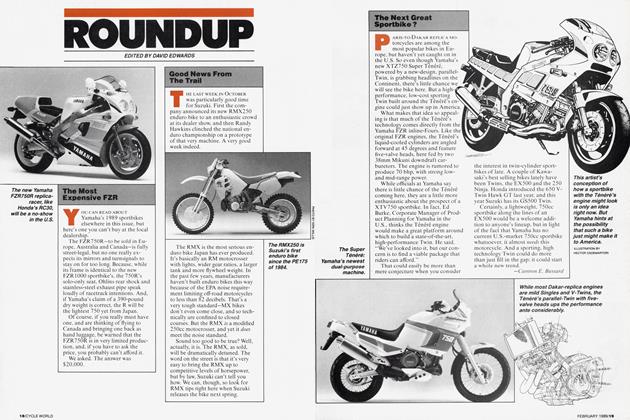

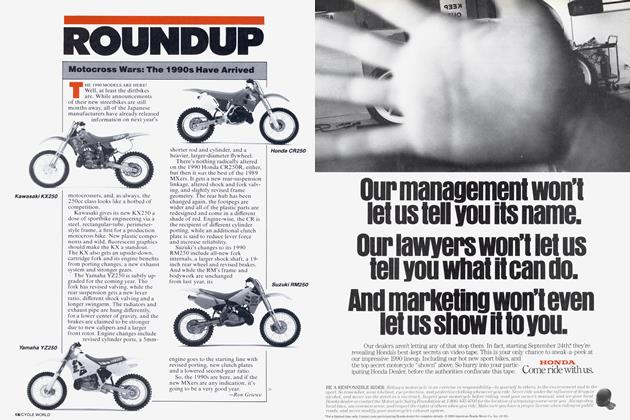

Roundup

RoundupMotocross Wars: the 1990s Have Arrived

October 1989 By Ron Griewe -

Roundup

RoundupThe Harley-Davidson Success Story

October 1989 By Jon F. Thompson