THE 555 TO FREEDOM

All you need to hit the road is desire, a little displacement and even less money. But it doesn't hurt to have a vast spiritual budget of mutual support and shared expertise. Beer and fireworks help, too...

BECKY OHLSEN

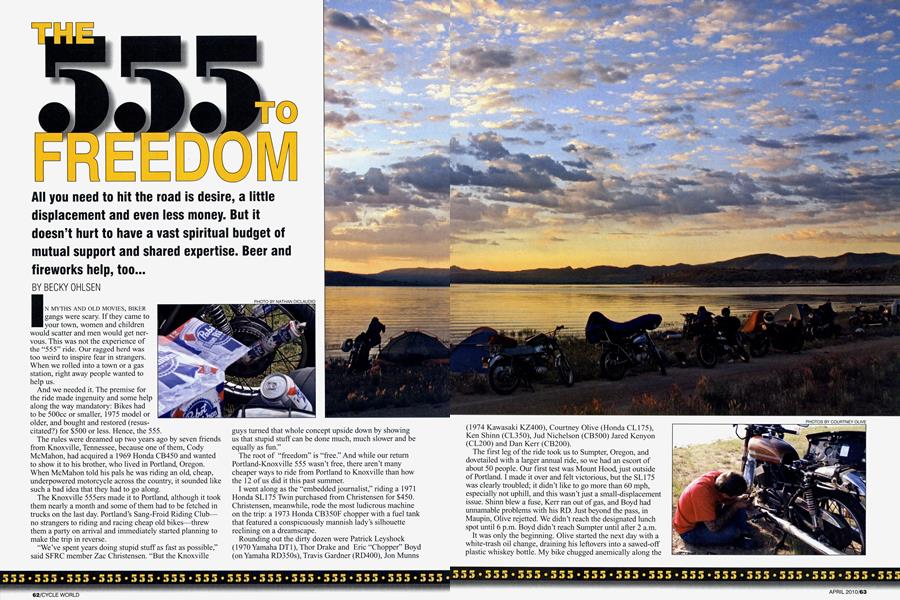

IN MYTHS AND OLD MOVIES, BIKER gangs were scary. If they came to your town, women and children would scatter and men would get nervous. This was not the experience of the "555" ride. Our ragged herd was too weird to inspire fear in strangers. When we rolled into a town or a gas station, right away people wanted to help us.

And we needed it The premise for the ride made ingenuity and some help along the way mandatory: Bikes had to be 500cc or smaller, 1975 model or older, and bought and restored (resus citated?) for $500 or less. Hence, the 555.

The rules were dreamed up two years ago by seven friends from Knoxville, Tennessee, because one of them, Cody McMahon, had acquired a 1969 Honda CB450 and wanted to show it to his brother, who lived in Portland, Oregon. When McMahon told his pals he was riding an old, cheap, underpowered motorcycle across the country, it sounded like such a bad idea that they had to go along.

The Knoxville 555ers made it to Portland, although it took them nearly a month and some of them had to be fetched in trucks on the last day. Portland's Sang-Froid Riding Clubno strangers to riding and racing cheap old bikes-threw them a party on arrival and immediately started planning to make the trip in reverse.

"We've spent years doing stupid stuff as fast as possible," said SFRC member Zac Christensen. "But the Knoxville guys turned that whole concept upside down by showing us that stupid stuff can be done much, much slower and be equally as fun.”

The root of “freedom” is “free.” And while our return Portland-Knoxville 555 wasn’t free, there aren’t many cheaper ways to ride from Portland to Knoxville than how the 12 of us did it this past summer.

I went along as the “embedded journalist,” riding a 1971 Honda SL175 Twin purchased from Christensen for $450. Christensen, meanwhile, rode the most ludicrous machine on the trip: a 1973 Honda CB350F chopper with a fuel tank that featured a conspicuously mannish lady’s silhouette reclining on a dreamscape.

Rounding out the dirty dozen were Patrick Leyshock (1970 Yamaha DTI), Thor Drake and Eric “Chopper” Boyd (on Yamaha RD350s), Travis Gardner (RD400), Jon Munns (1974 Kawasaki KZ400), Courtney Olive (Honda CL 175), Ken Shinn (CL350), Jud Nichelson (CB500) Jared Kenyon (CL200) and Dan Kerr (CB200).

The first leg of the ride took us to Sumpter, Oregon, and dovetailed with a larger annual ride, so we had an escort of about 50 people. Our first test was Mount Hood, just outside of Portland. I made it over and felt victorious, but the SL175 was clearly troubled; it didn’t like to go more than 60 mph, especially not uphill, and this wasn’t just a small-displacement issue. Shinn blew a fuse, Kerr ran out of gas, and Boyd had unnamable problems with his RD. Just beyond the pass, in Maupin, Olive rejetted. We didn’t reach the designated lunch spot until 6 p.m. Boyd didn’t reach Sumpter until after 2 a.m.

It was only the beginning. Olive started the next day with a white-trash oil change, draining his leftovers into a sawed-off plastic whiskey bottle. My bike chugged anemically along the 28 miles to Austin Junction, where Shinn diagnosed an electrical problem. He found a fried con nector, scraped off the blackened goo, reconnected it and electrical-taped the whole mess together. This cured the SL for about 30 minutes. A few towns later, Shinn found that one of my floats was now taking on fuel. We decided to fix it later; the faster guys were far ahead and wait ing for us. When we finally reached them, they'd been sitting in a truck-stop parking lot for three hours. We headed for a bar in Nampa, Idaho, to recharge.

This stop was in some respects the defining moment of the 555. We had arrangements to camp at the home of Mike Watanabe of the Idaho Vintage Motorcycle Club. We set up camp in Watanabe's back yard, invaded his well-equipped garage and a full-scale wrench party began. Shinn burned the extra fluid out of my leaky float and soldered it. He's a handy guy to know. Meanwhile, Kenyon, who had started the ride on a `79 XL500 in clear violation of the rules, lost his cheater bike on the first day of the ride thanks to a piston seizure. The reasonable thing to do when your bike implodes on Day One of a two-week motorcycle trip is to give up and go home. Instead, Kenyon doubled up with Nichelson on the CB500 and hoped we'd come across a 555-ready bike somewhere along the way. So, in Camp Nampa, everyone who wasn’t wrenching was using their phones to search craigslist for a replacement bike.

Finally, garage-host Watanabe offered, “You know, I do have this old CL200 in the barn, if you want to look at that.” We go look. It was under some boards, covered in barn dust. The chain was wadded up and rusty. It was missing carbs, among several other things. The boys wheeled it into the garage and dusted it off. It was turquoise, and the seat had a zipper down the middle, lengthwise, so the bike was dubbed “Sharky.” They pillaged carbs off another bike that Watanabe has been fixing up for someone else, soaked the rust off the chain, plugged the leaky petcock, did some voodoo magic, burned a little sage, turned around three times counterclockwise and fired it up. It ran perfectly the rest of the trip, even if all the others didn’t...

In fact, bikes broke down daily, and there were no chase trucks. This ride, in other words, wasn’t so much about riding. It was about solving problems and making things work, meeting strangers and seeing the country from an angle and at a pace none of us had experienced before.

The eventful string of breakdowns and other challenges, of course, were not unexpected. That’s why greasy-philosopher Ley shock’s pre-departure speech quoted from book five of Homer’s “Odyssey:” I wish you well, however you do it, but if you only knew in your heart how many hardships you were fated to undergo before getting back to your own country....

Munns, meanwhile, said repeatedly that this was the best motorcycle trip he’d ever taken. “I was looking forward to the breakdowns, the not knowing where you’d end up,” said Munns, who works for Fox Racing. “My whole life is planning, directing.”

Our next garage oasis came a few days later in Vernal, Utah.

I coasted in on one cylinder, but others were in worse shape. Munns lay on the floor of the garage, adjusting his bike with a, uh, hatchet. “The good thing about this,” he says of his latest bike trouble, "is it's gonna make it even easier to set her on fire when we get to Tennessee."

I'm not sure exactly what the hatchet was for-possibly morale. Munns was chasing the source of a death wobble that had grown steadily worse since we left Portland. A call to his mechanic back home proved fruitless. Advice from the distant, experienced voice was, “Don’t take your hands off the bars!” When a garbage truck rolled by, Munns said he thought they might be coming for our bikes.

Soldiering on toward Denver, after two high passes (one of them 11,307 feet!), the SL was spewing thick blue smoke as we rolled into town. Without a new top end, it would be going no farther. Luckily, it didn’t need to. Three of the 555ers had to bail, Kerr among them, but he wanted his CB200 to go the distance. So I retired the SL and took over his ex-vintage racebike with no mirrors, no taillight and GP shifting. The kickstart lever had been removed, so we rolled the bike to a nearby welding shop and asked the guys there to reattach it. Kerr handed me a flat stick of bamboo he’d been using as a sidestand. Good to go.

So many we met along the way had owned one of these bikes as a youth, or their cousin or dad had. People at gas stations came over to stare at the bikes and to give us bad advice about roads and good tips on camping. In small towns, the gas station is the hub of life. We spent a lot of time in these places, eating cold cans of beef stew and guzzling energy drinks, staring at maps, contemplating oil leaks and texting each other to see how far ahead the RD guys had gotten. People were invariably friendly, even if they doubted our sanity.

For long stretches, I followed Christensen on the chopper. If you stick your head inside one of those blow-dry helmets they have in old-fashioned hair salons, and you leave it there 10 hours a day for two weeks, you’ll start to understand what it’s like to ride 3000 miles behind a loud-piped, 1973 Honda CB350F chopper. Spectators loved it, though. Christensen took charge of chatting up the locals, gathering local intel on where to camp and eat. Every leg of the trip took us longer than we expected, so we were always scrambling to find a place to sleep. Given the various mechanical issues and topspeed differences, we often split into two or three groups between rallying points.

Our organizational style was anarchic; nobody wanted it any other way, but it did result in confusion. We relied heavily on text messages. Many nights we didn’t camp until well after dark, and we often went to bed without dinner, but never once without beer and a good campfire.

There were moments, I admit, when I believed the 555 might actually never end. Most of these moments had occurred in Kansas, where every road we found stretched off to the edge of the world like some smart-aleck’s statement on the futility of existence. Those roads ricocheted off both sides of your skull at once, and the best you could hope for was an interruption by a breakdown or a curious policeman. (We never worried too much about speeding tickets.)

Nonetheless, the end of the ride was inevitable, and it turned out to be sudden and explosive. At the intersection of 96 and 70 outside Monterey, Tennessee, the original Tennessee 555ers swooped in and intercepted us. After introductions, they led us to the farm of a guy called Johnny Walker, where they’d had their first major breakdown the previous year. The epic level of mischief that occurred that night had less to do with Tennessee moonshine than with the pure joy of meeting people who understood perfectly what we had just done (although the moonshine certainly contributed). A streetbike race in a muddy field and a lengthy fireworks battle caused more injuries than we’d accumulated in two weeks of riding. As Knoxville 555er Eric Ohlgren told a friend about our premature party, “ft was kinda like they’d made it—but they still had a hundred miles to go. Bikes were lost, bones were broken...”

Even after the 3377 miles we’d covered, the last 100 into Knoxville the next day seemed to take forever. We kept stopping, dragging it out. The satisfaction of completing such a huge and unlikely feat loomed close, but it would mean the ride was over. We were exhausted, existentially hungover, desperate for clean socks and hot showers, but nobody wanted to terminate our immersion in this strange freedom. So we did what any sane person would do: We started talking about the next 555 trip—dirt roads to Baja... □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

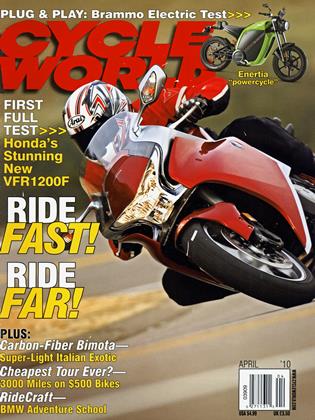

Up FrontBike of the Year

April 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

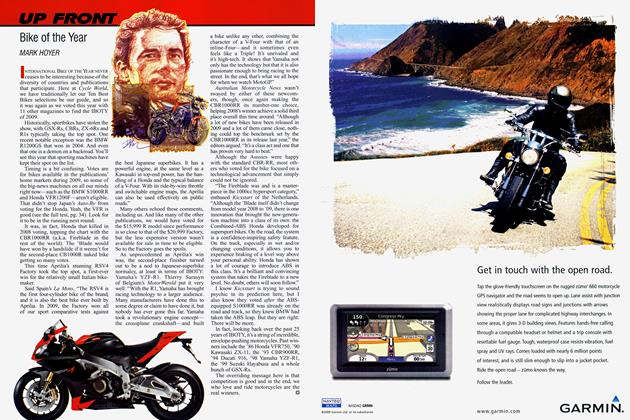

RoundupMeet the Motus

April 2010 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

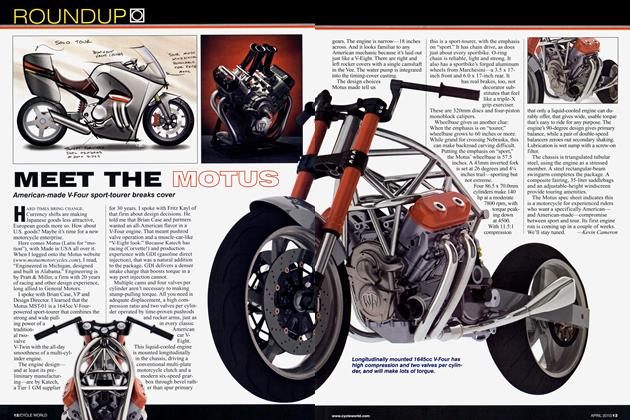

RoundupSuperbike For the Common Man?

April 2010 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupRide Like Rossi

April 2010 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago April 1985

April 2010 By Mark Cernicky -

Roundup

RoundupEtc...

April 2010