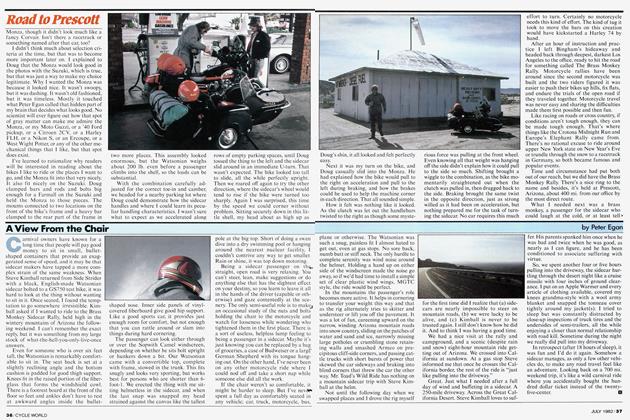

The Age of Tough Engines

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

I CRUISED OVER TO ONE OF OUR TWO local Honda shops last weekend to take a look at a used red 2001 Honda VFR800 they have for sale. It’s very clean, with about 8500 miles on the clock.

I must admit to a weakness for this generation VFR, even though I’ve steered away from four-cylinder bikes in recent years, generally preferring the torque and personality of Twins. But there is something in the sizzle and snap of that Honda V-Four I find quite soulful.

Nevertheless, I’m still at the mulling and pondering phase, looking around at other bikes as well. It’s a long winter, and what else have we got to do here in Wisconsin? If you think of anything else, besides drinking Guinness and watching the V-Four Victory Isle of Man video, send me a card.

Anyway, as I drove home from the dealership, it dawned on me that I had checked the VFR’s digital odometer, duly noted the mileage and dismissed that 8500 miles as a piffling trifle (sounds like an English pastry the Scarlet Pimpernel might eat), hardly worth mention.

Eighty-five hundred miles a trifle? That’s almost three full trans-continental crossings of the USA...

Yet the VFR is only about halfway to its first valve adjust. The O-ringed chain is still fine, and the bike looks clean enough to put back on the showroom floor as a new leftover. It’s had one set of new tires, four oil changes, and that’s its total service history.

As a guy who cut his teeth (and often his hands) on the bikes of the early Sixties, I find this sort of durability to be one of the biggest changes I’ve seen in motorcycling during my interminable yet fleeting lifetime. Motorcycle engines have gotten so good now, we almost think of them as sealed units. We still change oil and adjust valves once in a while, but very few people feel compelled to buy a complete shop manual with a new streetbike any more. Imminent replacement of crank bearings or valve guides is not really in the picture.

It’s a sobering thing to admit, but if you are my age or older (God forbid), the pistons and rings on your new bike will probably live longer than you will.

This is also true of the last bottle of aftershave you bought, but why be morbid? The plain fact is, unless you race-or spend your Golden Years entering Iron Butt rallies-you will probably never see the inside of your engine.

This is a nice change.

When I got into this sport, most nonJapanese bikes were still in the I VC (Infernal Vibratin’ Contraption) phase. BMWs were smoother and longer-lived than most, but they seemed to have achieved this excellence through a Devil’s pact in which they’d traded zesty performance for dogged reliability.

Other brands had shorter lifespans.

I’ve done restorations on two Triumph Twins and one Ducati Single from the Sixties, all of them (curiously) with almost exactly 12,000 miles showing, and they all needed serious engine work. Both Triumphs had worn-out valve guides, valves, pistons, rings, rod bearings, primary chains, sprockets and clutch baskets at that mileage. The Ducati had not been as hard on its own internals as the Triumphs, but it still needed cylinder-head work, and it had more electrical glitches than the Baghdad telephone exchange.

The point here is, all of them were disassembled and laid out on my workbench before they’d reached 13,000 miles. Or 3000 miles before that modern VFR needs its first valve check.

Japanese bikes, particularly Hondas, were the force of change that raised everybody’s expectations. They were oiltight, civilized, easy to live with and fast for their displacement. Critics (including me) pointed out that they were disposable consumer goods, generally not worth rebuilding once you wore them out, but you still got about three Triumph, Ducati or Harley engine rebuild lifetimes out of them before they had to be tossed. In the meantime, you had a lot of fun riding around and stayed out of the garage.

Depending upon your point of view, motorcycle engine rebuilding was either a Zen-like ritual of great spiritual importance or a huge drain on national productivity, like workdays lost to the flu. Most riders, once they realized there was no excuse for bad engines, came to see it as a version of the flu.

Now, of course, almost no one will put up with engine trouble from a bike, and manufacturers know it.

Triumph, once the posterbike for English Troubles (though certainly not the worst or only one), has resurrected itself on a bedrock of reliability. My riding buddy and fellow Slimey Crud, Toby Kirk, now has 90,000 miles on his 1995 Triumph Sprint without a single engine repair, and last year he blasted flat-out to the Southwest and back, just for some good Mexican food.

Imagine doing this on a 90,000-mile 1965 Bonneville. Assuming there ever was one.

I’ve had three modern-generation Ducatis and have yet to experience engine troubles with any of them (okay, a bad clutch cover gasket on the 900SS) despite long road trips and the relentless pounding of track days on my 996. At 12,000 miles they feel just broken-in.

Harleys? Well, every time I say Harley engines are bulletproof, I get about four letters from owners who’ve had some kind of cam trouble, but I never have. My Evo and Twin-Cam engines have been flawless on long, hot cross-country trips. Until personal experience proves otherwise, I consider them sealed units, as do most modern Harley owners.

This sort of progress is okay with me.

I still like to restore old bikes from the Sixties, but I don’t have a single gene in my body that longs to tear down a twoyear-old engine, just off warranty. Or to leave my greasy fingerprints on the “exploded view” of the engine cases in a shop manual-got plenty of those already; my Norton manual looks like the phone book at Al’s Lube Rack.

In fact, if I get that VFR, I might just pass on the shop manual entirely. At least until my aftershave runs out. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue