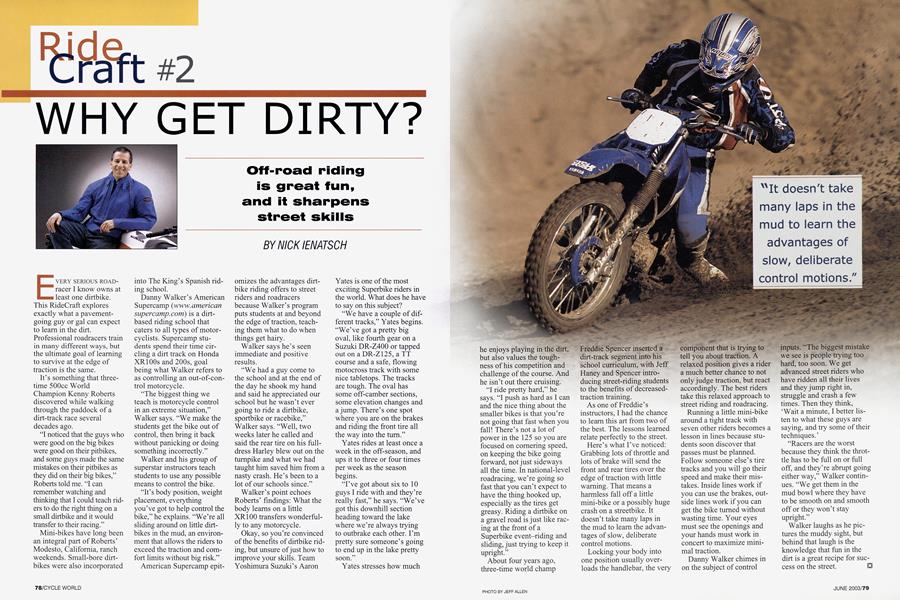

WHY GET DIRTY?

Ride Craft #2

Off-road riding is great fun, and it sharpens street skills

NICK IENATSCH

EVERY SERIOUS ROAD-racer I know owns at least one dirtbike. This RideCraft explores exactly what a pavement-going guy or gal can expect to learn in the dirt. Professional roadracers train in many different ways, but the ultimate goal of learning to survive at the edge of traction is the same.

It's something that three time 500cc World Champion Kenny Roberts discovered while walking through the paddock of a dirt-track race several decades ago.

"I noticed that the guys who were good on the big bikes were good on their pitbikes, and some guys made the same mistakes on their pitbikes as they did on their big bikes," Roberts told me. "I can remember watching and thinking that I could teach rid ers to do the right thing on a small dirtbike and it would transfer to their racing."

Mini-bikes have long been an integral part of Roberts' Modesto, California, ranch weekends. Small-bore dirt bikes were also incorporated into The King's Spanish rid ing school.

Danny Walker's American Supercamp (www.american supercamp.com) is a dirtbased riding school that caters to all types of motor cyclists. Supercamp stu dents spend their time cir cling a dirt track on Honda XR100s and 200s, goal being what Walker refers to as controlling an out-of-con trol motorcycle.

"The biggest thing we teach is motorcycle control in an extreme situation," Walker says. "We make the students get the bike out of control, then bring it back without panicking or doing something incorrectly."

Walker and his group of superstar instructors teach students to use any possible means to control the bike.

"It's body position, weight placement, everything you've got to help control the bike," he explains. "We're all sliding around on little dirt bikes in the mud, an environ ment that allows the riders to exceed the traction and corn fort limits without big risk."

American Supercamp epit omizes the advantages dirt bike riding offers to street riders and roadracers because Walker's program puts students at and beyond the edge of traction, teach ing them what to do when things get hairy.

Walker says he's seen immediate and positive results.

"We had a guy come to the school and at the end of the day he shook my hand and said he appreciated our school but he wasn't ever going to ride a dirtbike, sportbike or racebike," Walker says. "Well, two weeks later he called and said the rear tire on his full dress Harley blew out on the turnpike and what we had taught him saved him from a nasty crash. He's been to a lot of our schools since."

Walker's point echoes Roberts' findings: What the body learns on a little XR100 transfers wonderful ly to any motorcycle.

Okay, so you're convinced of the benefits of dirtbike rid ing, but unsure ofjust how to improve your skills. Team Yoshimura Suzuki's Aaron Yates is one of the most exciting Superbike riders in the world. What does he have to say on this subject?

"We have a couple of dif ferent tracks," Yates begins. "We've got a pretty big oval, like fourth gear on a Suzuki DR-Z400 or tapped out on a DR-Z125, a TT course and a safe, flowing motocross track with some nice tabletops. The tracks are tough. The oval has some off-camber sections, some elevation changes and a jump. There's one spot where you are on the brakes and riding the front tire all the way into the turn."

Yates rides at least once a week in the off-season, and ups it to three or four times per week as the season begins.

"I've got about six to 10 guys I ride with and they're really fast," he says. "We've got this downhill section heading toward the lake where we're always trying to outbrake each other. I'm pretty sure someone's going to end up in the lake pretty soon.,'

Yates stresses how much he enjoys playing in the dirt, but also values the toughness of his competition and challenge of the course. And he isn’t out there cruising.

"It doesn't take many laps in the mud to learn the advantages of slow, deliberate control motions."

“I ride pretty hard,” he says. “I push as hard as I can and the nice thing about the smaller bikes is that you’re not going that fast when you fall! There’s not a lot of power in the 125 so you are focused on cornering speed, on keeping the bike going forward, not just sideways all the time. In national-level roadracing, we’re going so fast that you can’t expect to have the thing hooked up, especially as the tires get greasy. Riding a dirtbike on a gravel road is just like racing at the front of a Superbike event-riding and sliding, just trying to keep it upright.”

About four years ago, three-time world champ Freddie Spencer inserted a dirt-track segment into his school curriculum, with Jeff Haney and Spencer introducing street-riding students to the benefits of decreasedtraction training.

As one of Freddie’s instructors, I had the chance to learn this art from two of the best. The lessons learned relate perfectly to the street.

Here’s what I’ve noticed: Grabbing lots of throttle and lots of brake will send the front and rear tires over the edge of traction with little warning. That means a harmless fall off a little mini-bike or a possibly huge crash on a streetbike. It doesn’t take many laps in the mud to learn the advantages of slow, deliberate control motions.

Locking your body into one position usually overloads the handlebar, the very component that is trying to tell you about traction. A relaxed position gives a rider a much better chance to not only judge traction, but react accordingly. The best riders take this relaxed approach to street riding and roadracing.

Running a little mini-bike around a tight track with seven other riders becomes a lesson in lines because students soon discover that passes must be planned. Follow someone else’s tire tracks and you will go their speed and make their mistakes. Inside lines work if you can use the brakes, outside lines work if you can get the bike turned without wasting time. Your eyes must see the openings and your hands must work in concert to maximize minimal traction.

Danny Walker chimes in on the subject of control inputs. “The biggest mistake we see is people trying too hard, too soon. We get advanced street riders who have ridden all their lives and they jump right in, struggle and crash a few times. Then they think,

‘Wait a minute, I better listen to what these guys are saying, and try some of their techniques.’

“Racers are the worst because they think the throttle has to be full on or full off, and they’re abrupt going either way,” Walker continues. “We get them in the mud bowl where they have to be smooth on and smooth off or they won’t stay upright.”

Walker laughs as he pictures the muddy sight, but behind that laugh is the knowledge that fun in the dirt is a great recipe for success on the street. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue